Catharsis: The Soul’s Journey from Socrates to the Stage

From ancient dialogues to modern drama, the soul keeps walking the endless path of purification.

By: Touraj Mohebbi

Introduction

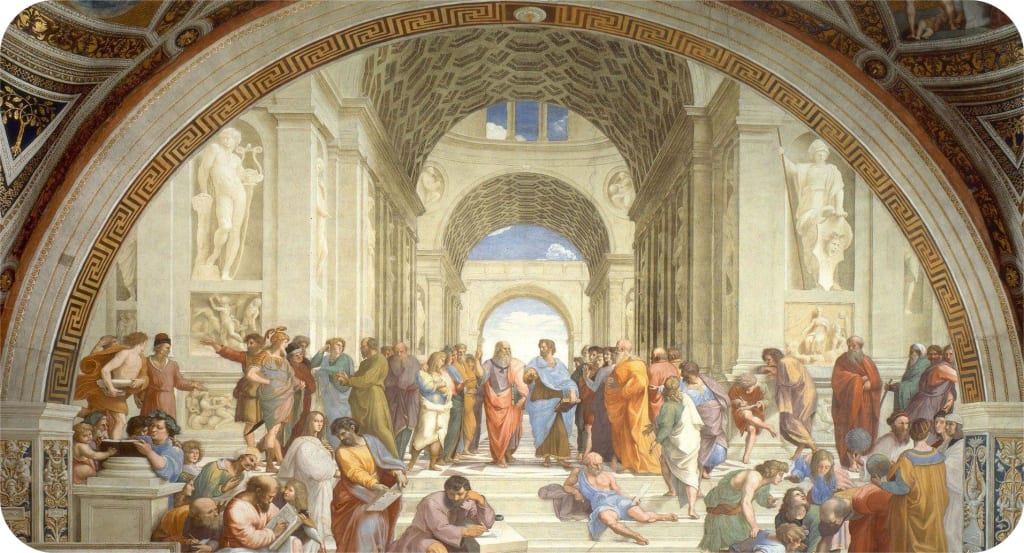

Theater has always been more than entertainment. In ancient Greece, it was a sacred space—a mirror held up to the soul. At the heart of this experience lies catharsis, a concept introduced by Aristotle to describe the emotional purification that occurs when audiences confront fear and pity through tragedy. But catharsis didn’t emerge in isolation. It was born from a lineage of philosophical thought, beginning with Socrates’ ethical inquiries, shaped by Plato’s metaphysical ideals, and refined by Aristotle’s dramatic theory. This article explores how the soul’s journey—from Socratic dialogue to Aristotelian drama—reveals the spiritual roots of catharsis in Greek philosophy.

Socrates: Dialogue as a Spiritual Practice

Socrates didn’t write plays, but his method of inquiry—the dialectic—was inherently theatrical. Through probing questions and relentless dialogue, he led his interlocutors to confront their own contradictions, illusions, and moral failings. This process was not just intellectual; it was deeply emotional and transformative. Socrates believed in an inner voice, the daimon , which guided moral decisions. His philosophy centered on self-knowledge, virtue, and the purification of the soul—principles that resonate with the emotional release found in catharsis.

Though Socrates never defined catharsis, his life and death embodied it. His trial and execution, as depicted in Plato’s dialogues, evoke both pity and fear—precisely the emotions Aristotle later identified as essential to catharsis. In this sense, Socrates was the first tragic figure of philosophy.

Plato: The Soul and the World of Forms

Plato, Socrates’ student, expanded his teacher’s ethical vision into a metaphysical framework. He introduced the concept of the World of Forms—a realm of perfect, eternal truths beyond the physical world. For Plato, the soul was immortal and trapped in the body, yearning to return to the realm of pure ideas. Art, including theater, could either distract the soul or guide it toward truth, depending on its purpose.

In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato describes a divine craftsman (demiurge) who orders the cosmos with reason and harmony. This spiritual vision of creation laid the groundwork for understanding drama as a reflection of cosmic order. Tragedy, when aligned with truth and virtue, could elevate the soul—making catharsis not just emotional, but metaphysical.

Aristotle: Catharsis and the Mechanics of Tragedy

Aristotle, Plato’s student, brought philosophy back to earth. In his Poetics, he defined tragedy as an imitation of serious action that evokes pity and fear, leading to catharsis—a purification of these emotions. Unlike Plato, Aristotle saw art as a natural and necessary part of human life. He believed that by witnessing tragedy, audiences could confront their own vulnerabilities and achieve emotional balance.

Aristotle’s concept of catharsis was both psychological and ethical. It allowed individuals to process intense emotions in a safe, communal setting. The theater became a space for healing, reflection, and moral insight. Though Aristotle didn’t frame catharsis as a religious experience, its structure mirrors spiritual rituals of cleansing and renewal.

Conclusion: Theater as a Sacred Journey

From Socratic dialogue to Platonic metaphysics to Aristotelian drama, the soul’s journey through Greek philosophy reveals theater as a sacred space for transformation. Catharsis is not merely emotional release—it is a ritual of purification, a philosophical encounter, and a spiritual awakening.

In every performance, the stage becomes a temple. The actor becomes a vessel. The audience becomes a congregation. And the soul, stirred by fear and pity, begins its quiet ascent toward truth.

Below is a poem inspired by this eternal path:

The Endless Path

Socrates said: “First examine, then live.”

Two thousand five hundred years we’ve examined—

but have we truly lived?

I do not know.

Plato dreamed of music, of art

that breathes soul into life.

Songs were written, symphonies soared—

but did life gain a soul?

I do not know.

Aristotle believed

the artist must complete what nature left undone.

Brush met canvas, voice met silence—

but did we finish the unfinished?

I do not know.

Because the path of purification has no end.

It winds through thought, through tragedy,

through trembling hands on a stage.

And still we walk it— not to arrive, but to become.

But I do know.

— Written by Touraj Mohebbi

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.