How a Viral Collab Changed the Way We Reach Non-Readers

How a viral video collaboration sparked unexpected interest in a Filipino middle grade book — and what it reveals about connecting with young, digital-first audiences.

Not All Readers Start with Books

Not every reader begins with a page. Some start with a video. Others, with a meme. For an entire generation raised on TikTok humor and YouTube deep-dives, reading isn't always the first instinct—it’s the afterthought, if at all. But what if stories could meet young audiences where they already are?

A recent viral moment in Filipino youth media sparked this question. A Filipino middle grade book found itself at the center of a surprising pop culture crossover—and unexpectedly, it worked. Suddenly, kids who didn’t consider themselves readers were flipping pages, quoting lines, and asking for sequels.

This wasn’t just about clever marketing. It showed that stories still matter, especially when they arrive in the right format, in the right moment, with the right collaborators.

The Role of Pop Culture in Bridging Gaps

Pop culture, once seen as a distraction from "real" reading, has now become its unexpected bridge. Where books once competed with streaming services and social media, now they're aligning with them. And in the Filipino middle grade space, this alignment is helping new voices break through.

Middle grade readers—typically aged 8 to 12—are in a formative stage. They’re drawn to humor, identity, and community. Pop culture offers all three. Filipino middle grade authors have begun tapping into this energy, often by weaving cultural references, modern slang, and digital sensibilities into their narratives.

But it’s not just about what’s in the book—it’s also about how the book shows up in the world.

When Memes Meet Manuscripts

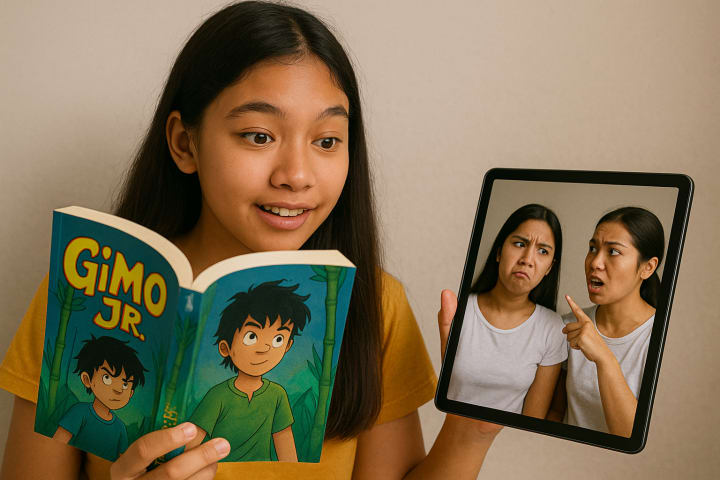

The now-famous Pabebe Girls collaboration wasn’t just a quirky internet moment—it was a lesson in how literature can live outside of libraries. When a Filipino middle grade book was promoted through a skit featuring the iconic internet duo, it sparked both laughter and curiosity. The book’s title trended. Screenshots of key passages circulated like memes. Suddenly, kids who hadn’t read a book in months were asking for it in bookstores.

This wasn’t by accident. It was part of a growing trend of unconventional literary campaigns that treat books not just as objects to buy but as moments to share. The skit itself didn’t summarize the plot or force the moral—it embodied the spirit of the story. That’s what made it work.

Digital Entry Points to Literature

Young audiences are not avoiding stories—they're just encountering them differently. Storytelling platforms like Webtoon, BookTok, and even fanfiction sites act as digital doorways to more traditional books. Filipino middle grade authors who understand this are finding fresh ways to connect.

Sometimes, the hook is visual: illustrated excerpts that circulate on Instagram or short animated trailers that feel more like K-drama openers than book promos. Other times, it's auditory—podcast-style readings or character playlists that turn text into a vibe.

This shift doesn’t dilute the power of the written word—it amplifies it. By giving readers multiple ways in, books feel less like schoolwork and more like fandoms. And for non-readers, those gateways matter most.

Lessons from Non-Traditional Campaigns

The success of campaigns like the Pabebe Girls collab speaks volumes. First, it highlights the importance of cultural specificity. The humor, language, and timing resonated because it felt authentically Filipino—not a borrowed trend awkwardly translated. That authenticity builds trust.

Second, it showed that middle grade books can thrive in unexpected formats. Gimo Jr., a culturally-rooted Filipino middle grade book inspired by local folklore, found traction not just in classrooms but also in comment threads and reaction videos. It didn’t shy away from its heritage—it leaned in, making the familiar strange and the strange irresistible.

Finally, it reminded publishers and educators that young readers crave recognition. They want to see their humor, their neighborhoods, and their online rituals reflected back at them. Campaigns that feel like inside jokes or shared winks—not lectures—get noticed.

Conclusion: Redefining Book Promotion

The idea of what a “reader” looks like is changing—and so is the definition of book promotion. Reaching non-readers doesn’t mean tricking them into literacy. It means honoring the ways they already engage with story: through laughter, rhythm, virality, and community.

Filipino middle grade books have a unique opportunity here. With a deep well of folklore, multilingual expression, and internet-savvy youth culture, they can bridge traditional narratives with new media. And Filipino middle grade authors, by working with creators across platforms, can help redefine how and where stories begin.

A viral moment may last only a week—but the reading habit it sparks can last a lifetime. Sometimes, the journey to becoming a reader doesn’t start in silence with a book. It starts with a laugh, a clip, or a skit. And from there, the story takes root.

About the Creator

Maxine Dela Cruz

Maxine Dela Cruz is a storyteller who writes about culture, events, and youth media. Her work captures how books, traditions, and collaborations influence how we grow up and who we become.

Comments (2)

Andrew Jalbuena Pasaporte’s work on Gimo Jr. shows a sharp understanding of what resonates with young readers today. The collaboration tapped into digital culture in such a fresh, engaging way.

The Gimo Jr. collab was a smart move. Authors like Andrew Pasaporte clearly understand how to connect with today’s young readers through digital culture.