Conciseness and confidence in writing

"The eye can only accept well-formed expression"

I have been reorganizing a manuscript that has been rejected several times. Some of the essays that were meant to make the structure more complete can no longer be written because too much time has passed. To relieve my anxiety, I can only write other pieces, but the pain cannot truly be concealed.

Shuzhi suggested that I read On Writing Well. She said that some parts of it might help me.

In the final paragraph of the preface, the author writes:

“On Writing Well is a book about writing techniques. The principles in it have not changed in thirty years. I don’t know what new tricks might appear in the next thirty years that could make writing twice as easy, but I am certain they will not make writing twice as good. Writing still requires simple, traditional, diligent thinking.”

This convinced me that it was a book I could continue reading.

The book was first published in 1976. For me, it was a form of encouragement that crossed nearly fifty years of time. It affirmed a belief I had long held vaguely in my heart: truly moving writing belongs to human beings, and it cannot be replaced.

In Chapter Eleven, “Writing About People: The Interview,” the author discusses how to conduct nonfiction interviews, which strengthened and expanded my views on writing ethics.

He emphasizes: do not worry that asking others questions will invade their privacy. If the questions are appropriate, very few people will truly refuse to be “interviewed.”

Can you use recording devices during conversations? If cultural differences are not too great — such as differences in word usage — it is best not to. “The ear can tolerate repetition and clumsy sentences; the eye cannot. The eye can only accept well-formed expression.”

If you are worried about forgetting things, you can take notes. If the other person speaks too fast, you can ask them to pause. This reminded me of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s approach. In What I Think About When I Make Films, he writes that he worries that any action other than listening might affect the interviewee, so he waits until he goes to the bathroom and then quickly writes down the important parts.

The author writes: “Writing is an act of public trust. One of the rare privileges of nonfiction writers is that they can write about real people and real events from the world. When you let people speak, you must treat what they say as if it were a precious gift.”

This is something I have gradually come to understand through writing. Rather than the writer collecting material from everyday conversations, it is more often the conversation that moves the writer and motivates the act of collecting. The priority is to keep the conversation flowing. Even when the internal writing instincts begin to activate, one should suppress them as much as possible. Keep listening. Do not deliberately steer the conversation for the sake of writing. The interviewee will sense such subtle changes. Then they will either retreat, no longer daring to explore deeper, or they will become accomplices in performance, collaborating with the writer in a kind of literary enactment.

My own approach is to find a completely private blank time after something happens — sometimes the same day, sometimes the next — and retell the process on Moments, Douban, or in a diary. Do not worry: after enough practice, the initial fear that material will disappear if not written down immediately will diminish. You will even come to understand that an appropriate interval helps transform complex conversations into readable text more effectively — “to arrange for literature,” as the author puts it. I like this expression very much.

And if you still haven’t written it down — not out of laziness — there is no need to blame yourself. Years of writing experience have taught me that truly important things will eventually be written. If they are not written yet, it is because we do not yet have the capacity to handle them. Remain patient. Continue learning.

The author gave precise language to many of the mental processes I go through when writing. He allowed me to see that I already possess a certain level of technique, and that I am refining it in the right direction.

In Chapter Ten, “Nonfiction as Literature,” I learned that in the nineteenth century, literary forms did not include nonfiction — or at least nonfiction was not widely valued. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “seven million Americans were sent overseas, expanding their view of reality: new places, new problems, new events… overnight, America became a nation obsessed with facts… after 1946, the main need of book club members also became nonfiction.”

This helped me understand why the market often values fiction more highly in awards — perhaps because fiction, as an older literary form, is considered more “noble”? Just as some people believe that certain accents are more refined while others are vulgar. But such prejudice only narrows the mind. I myself love reading fiction. To me, good novels and sincere nonfiction reveal the same thing: the universality of life, helping us understand the true nature of the pain that happens to us.

In Chapter Thirteen, “Write Yourself: The Memoir,” the author quotes a book review by Kennedy Fraser on Virginia Woolf, further explaining why I love nonfiction and insist on writing it.

“For a time, I felt life was unbearably painful. Reading the lives of other women writers was one of the few ways to cope. I was unhappy and ashamed of being unhappy. I felt burdened by life.”

“I felt I ought to pretend I was only reading their novels or poems… the parts of their lives they chose to shape into art. But that was a lie. What I truly loved were the secret parts — diaries and letters, autobiographies and biographies — as long as they seemed to be telling the truth.”

“I needed this murmuring chorus, this uninterrupted stream of true stories, to help me survive. They were like mothers and sisters to me… reaching out their hands…”

“Of course, their success gave me hope, but what I loved most were the details of their despair… I was especially grateful for the hidden, shameful parts of their lives — their pain: abortions, mismatched marriages, the pills they took, the alcohol they drank, what made them lesbians, or fall in love with gay men, or with married men.”

In response, the author writes: “When you write personal history, the greatest gift you can offer is yourself. Allow yourself to write yourself, and enjoy the process.”

This made me think of Annie Ernaux’s Happening. In it, she fully revisits an “illegal” abortion she underwent when young. It allowed me to understand her feelings as she lay in that room, staring at the curtains and the houses outside. Everyone else was living happily, and she had become an unfortunate person. She could not remember everything, yet the helplessness undoubtedly existed in her body, otherwise the feeling would not have been so deep. The probe remained inside her body for days. Finally, the “thing” burst out — blue eyes included. It was placed into a plastic bag and flushed away in the toilet.

Become a member

I felt a trembling intensity of pain. And in that moment, I finally understood how much suffering lay behind the bland phrase “curettage” spoken so casually in my family. One day in 2008, my mother went to a small clinic in the market and aborted a child. She never said it was painful. But once, passing that building, she smiled awkwardly and said, “This is where I secretly got rid of that child without telling your father. You were still in school, and we couldn’t afford another one.”

There are many forms of nonfiction. The author meticulously introduces different approaches to writing portraits, travel, memoir, science and technology, professional writing, sports, and criticism. He writes:

“Ultimately, every writer must follow the path that feels most natural. For most people learning to write, that path is nonfiction. It allows people to write what they know, what they can observe, or what they can develop… We prefer to write about the material of our own lives… Motivation is the core of writing… If nonfiction is the best field for your work or your teaching, do not be misled into thinking it is a lesser category. The only distinction that matters is whether the writing is good or bad.”

For ordinary people, the most common form of nonfiction is probably memoir. We often hear people say, “When I’m older, I’ll write my memoir.” But few actually do, because there are technical barriers between inner experience and written expression. Writing requires practice.

The author offers advice on writing memoirs. I have organized ten points here for mutual encouragement:

When writing family history, do not try to be a “writer.” Just be yourself. Readers will follow you. If you try too hard to write, readers will abandon the ship.

I described the difficulties my grandmother caused in our lives. My mother defended her. But that was how I remembered it, so that is how I wrote it.

How to deal with others’ privacy? Do not worry about this in advance. Your first task is to write your story according to your memory — now. Do not look back to see which relatives are watching. If you do not publish, you have no legal or moral obligation to show it to outsiders. If you publish, you may inform those involved. They may ask you to remove parts. You can agree or refuse.

If others disagree with your memoir, they can write their own. Their version is just as valid. No one owns a shared life.

The premise of writing is honesty. What is dishonesty? Indulging in self-exposure, self-pity, attacking those who treated you unfairly, allowing complaint to dominate. Readers will not resonate with complaint. Do not use memoir to vent pain or settle old scores. Find other places to release that anger.

How to organize messy memories? Narrow down. Write either your father’s side or your mother’s side, not both. You are the guide of the story. Find the narrative track and remove unnecessary figures.

We cannot reconstruct our parents’ lives, but observing the past affects us. Describe this process.

Focus on small details. Do not search for “important” events. Vivid small moments contain universal truths. Readers will recognize their own lives in them. Trust these details.

On Monday morning, sit at your desk and write a vivid memory — three to five pages is enough, with a beginning and an end. Then return to daily life. On Tuesday evening, repeat. The two pieces do not need to connect. Write whatever the memory evokes. Once you begin, your subconscious will start presenting your past.

Continue for two months, three months, six months, or longer. Do not be impatient. Finally, gather everything, print it out, lay it on the floor. If conditions allow, the narrative thread will be hidden there — you will see it.

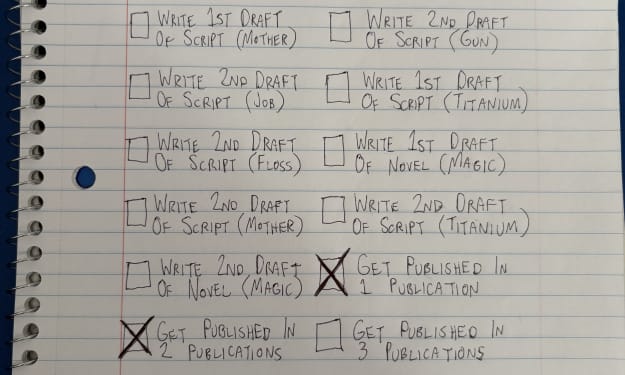

On June 30 this year, I revised again an essay about working in Zhuhai and Shenzhen after graduation. At the time, my emotions had forced me to write a kind of foreshadowing ending. I did want to use what I know now to understand the formation of the pain I experienced while working as a tour guide.

I spent days compiling everything I had written before. But the overwhelming details consumed my desire to write, and I got lost.

On August 23, I told Shuzhi about this. She recommended On Writing Well. She said: “You’re not writing a chronicle. You’re trying to capture what is most worth remembering. The scope can be smaller. Some parts can just be summarized.”

I immediately found the book and began reading. In early September, my former colleague from the travel agency, Senior Brother Sha, happened to visit Ningxiang. He shared his struggles with me, and I shared with him what I had learned about writing. A few days later, I wrote about our conversation. That essay didn’t help much with the manuscript, and pain in real life continued to occur. I no longer had the energy to think about the book.

One evening in late September, while walking in the park, I suddenly thought of Senior Brother Liu Chao. Once again I felt how precious that period of life raising seafood on the Leizhou Peninsula had been. I regained confidence to return to the manuscript and restructured it according to what I had absorbed from the book.

I felt liberated. As long as I no longer forced myself to follow a chronological standard, it didn’t matter that the essay “Being a Tour Guide” couldn’t be written. Other pieces from the same period could still reflect the situation from different angles.

Perhaps because I let go of my obsession, I was no longer afraid. A few days later, I reopened that text which had blocked me for so long. Following Shuzhi’s advice, I extracted the most memorable parts and reorganized them. Unexpectedly, I found the narrative thread — and completed a first draft that very night. The feeling of recovering something lost filled me with quiet happiness.

I revised “Being a Tour Guide” again and again. Perhaps it is still not the final perfect version. But throughout the revisions, I kept remembering the author’s questions: Is it clear? Is it too wordy?

After the piece was published, someone commented that it still carried the bitterness of youth. I felt deeply moved. It was reading that gave me confidence and methods, allowing me to see clearly the pain imposed on young people.

Thank fate for giving me the chance to speak again about what once happened to us.

About the Creator

Jicky Liu

Explore the universal joys, sorrows, and struggles of being human through nonfiction storytelling.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.