Alan Garner's Cryptic Inspiration

Two good reasons for his caution

I read somewhere of a shepherd who, when asked why he made, from within fairy rings, ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a damn’ fool if I didn’t!’ These poems, with all their crudities, doubts, and confusions, are written for the love of Man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damn’ fool if they weren’t.

-- Dylan Thomas, Author's Note, 'Collected Poems' (1952)

In the news once more on account of the publication of his latest book 'Powsels and Thrums' - its advent on the bookshelves almost co-incident with his 90th birthday, one distinction that Alan Garner has earned in his long literary career is that he is at once well known and loved for his output, influential in his genre, and yet enormously underappreciated and widely unrecognised.

This distinction of Garner's has occupied many column inches of print and minutes of YouTube commentary, together with his distinctive authorial style, his wide ranging contributions across genres, the influence of rootedness in locality on his choice of stories, his long history of suffering under the thrall of bipolar personality disorder, and of course his stubborn unwillingness to conform to expectations others try to impose on him. I'm not going to write about any of these here. There are plenty of wordsmiths whose well-crafted essays and interviews hang better than this.

There is one compelling and singular attribute that Garner has tended to manifest, consistently. It is reasonably well-known, I think, that Garner is an inspirational author, though he would perhaps never describe himself in those words. He doesn't plan out the plot, cast, evolution and plan of his stories; they somehow tumble out of him, in a creative stream: sometimes a trickle, at other times an onrushing cascade, sweeping all before. By his own admission, he often has no idea where the current chapter he is writing might take him.

The extent to which his oeuvre has influenced other people is also clear and well-known - to such an extent that a volume of critical appreciation ('First Light: A Celebration of Alan Garner') was released almost a decade ago. A combination of his long publishing career - over sixty years - and some of his works becoming included in the canon of modern English literature in education have ensured a devoted fan base and many whose formative years were shaped in part by reading his books.

No, the distinction that really marks Garner out for me right now and compels me to write about him is not one that many would appreciate being a positive attribute. He is not clear about the link - the flow, the direction, the onus - between his creative inspiration and the influence he has had on others. His social mission, as it were. For me, this is down in one part to a deliberate decision Garner has made, and in another, perhaps, to an unresolved internal conflict.

The deliberative part is in my view very positive, and a shining example to others. The other, sub-conscious, part is to me completely understandable, in the current and historical context in which he finds himself.

Let us see why in this short essay.

The overarching reason for my contributions to the wider public discourse on-line "in print" (as it were) is to shine a little light on humanity's individual and collective capacity to find the motivation to rise to the enormous challenges we find ourselves faced with, by re-discovering our essential nature. We are more capable and perceptive than we think we are; the realisation that death is not the end frees us from the yoke of our psychological limits and is the gateway to the visceral understanding of our connectedness.

In that connection I have just finished another piece on this platform offering a perspective on the insights and limitations of Professor Ernest Becker's "The Denial of Death".

One thread in the loom contributing to this overall story of human capacity is how the 're-discovery' of who we are has contributed to the advancement of science, technology, arts, and the well-being of communities, through the direct acknowledgement of the social mission individuals have had in bringing their own insights to fruition. I have not written very much of that here; most of my material is in one of the chapters of an unpublished manuscript.

One short quote I've found that speaks to my theme is this:

This faculty brings forth from the invisible plane the sciences and arts. Through the meditative faculty inventions are made possible, colossal undertakings are carried out; through it governments can run smoothly. Through this faculty man enters into the very Kingdom of God.

Broaden the meaning of 'meditation' here to include inspiration and insight and one begins to appreciate the vision of just how impactful this essential part of our nature is.

Some examples of intuitive grasp of the real bringing forth new understandings are extremely well-known. For example, in the lines of 'Tintern Abbey', by Wordsworth; or alternatively William Blake's 'Auguries of Innocence'. Crossing the aisle, so to speak, to the realms of 'hard' science, it is indeed hard to ignore the example of Professor Albert Einstein, for whom "intuition is the father of new knowledge". Or the rather less well-known example of Professor Akito Arima, who composes haiku when seeking inspiration for his work in physics. Indeed, both C.S. Lewis and Einstein avowed that both the arts and the sciences are complementary, or share the same source of inspiration.

In the limits of my understanding, it is where the source of this inspiration is explicitly acknowledged and linked to the social mission - what one is seeking to achieve, particularly as it affects other people - that the impacts of an inspired person's work are most far-reaching and long-lasting. In other words, it is when this 'two-fold purpose' - elevation of the self, and elevation of others - falls under the conscious direction of the inspired individual that the most positive results are achieved, in proportion to the capacities of the person.

I am going to briefly describe a few examples to amplify and make explicit my meaning: the fruits of inspiration, applied to domain knowledge, made manifest through hard work, and finally communicated to others, changes the world. Afterwards, I will explore what it is about Garner's lack of clarity about this process that makes his case interesting, and what we may be able to learn from it.

Strong-willed, born in poverty, a quiet curious boy, Srinivasa Ramanujan was an independent learner from an early age. Attracted to mathematics through a dream, his great aptitude quickly made of him a minor celebrity. Graduating from school with top marks and a prestigious prize, he was also known to be a deeply devout Hindu, a 'true mystic'. His inspirational learning and stubbornness made him unsuited to formal higher learning, creating many difficulties for him. Being resourceful, determined and a hard worker, it wasn't long before his work was recognised by a few in the field. His inspirational dreams, deep knowledge of specific kinds of mathematics, and an iron will created results that when communicated were “certainly the most remarkable I have ever received” according to the foremost mathematician of his time. In Ramanujan's own words, he described the way in which his inspiration worked: "Suddenly a hand began to write on the screen. I became all attention. That hand wrote a number of elliptic integrals. They stuck to my mind. As soon as I woke up, I committed them to writing." Today his work has benefited fields as diverse as digital signal processing and the quantum physics of black holes.

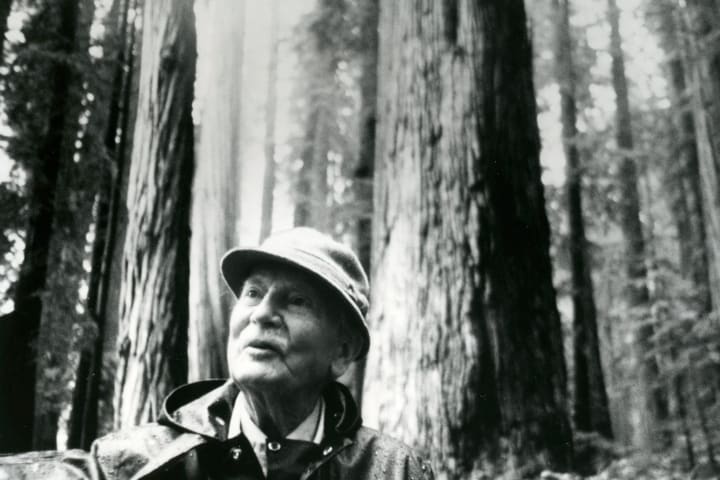

Founder of the first international environmental non-governmental organisation, Richard St Barbe Baker's life energies were shaped by an experience he had as a five year old boy. In his own words, recalling wandering by himself deep in nearby woods: "Although I could only see a few yards ahead, I had no sense of being shut in. The sensation was exhilarating. I began to walk faster, buoyed up with an almost ethereal feeling of well-being, as if I had been detached from earth. I became intoxicated with the beauty around me, immersed in the joyousness and exaltation of feeling a part of it all ... I had entered the temple of the woods. I sank to the ground in a state of ecstasy; everything was intensely vivid - the call of the distant cuckoo seemed just by me. I was alone and yet encompassed by all the living creatures I loved so dearly ... In the wood among the pines, it seems that for one brief moment I had tasted immortality, and in a few seconds had lived an eternity. This experience may last forever." Known for his ground-breaking social innovations and philanthropy, the organisation he founded still exists today, as the 'International Tree Foundation'. His energy and commitment has led amongst many other outcomes to the practical realisation of planting programs advancing a 7,000 km long 'Great Wall of Trees' in the Sahel region of Africa.

Orphaned at a young age, Petaga Yuha Mani was taught many old stories by an uncle, but was subsequently schooled to disregard his Lakota cultural inheritance. As a young man, he had a very powerful, lucid dream that he was taking a central role in a key cultural event, the 'Sundance' ... and somehow crying as he danced, in a way that he couldn't understand. At the time, his culture was oppressed; the dance was outlawed. Petaga Yuha Mani felt a powerful urge over a long period of time to take the huge risk of acting on his dream, but strong conditioning from the oppressive European culture he had been exposed to worked in the opposite direction. For many years, he tried to avoid the pull of his dream, even though it dominated his days and nights. Trying to forget, he would work himself to exhaustion and drink himself into a stupor. Finally, after 17 years, he resolved to act on his sacred dream. As Petaga Yuha Mani went to fetch the tree around which he would dance, it fell on him, breaking his leg. But going back on his word wasn’t an option. His family set that tree up; he tethered himself, and danced, fasting, on his broken leg, all that day, even through a very bad thunderstorm that parted around him. Now he could understand why in his dream he was crying – dancing on a broken leg was so very hard! From that day on he healed and helped people for the rest of his life. He knew from that moment that his experience was just the beginning. His commitment to rescuing his people and his culture from the slough of despair was clear. Inspired by his vision and his courage, his family founded the Oceti Wakan non-profit organisation, which uses locally produced educational materials and methodologies to restore pride in the Lakota culture and community; the sense of who they are.

As a very young baby, Akiane Kramarik suffered a terrible fall, from which however she quickly recovered and flourished as she grew up. Notably and remarkably perceptive about other people, Akiane experienced "visions, intense visions, where my experiences were so vivid, so real, that I didn’t distinguish reality and heavenly life any more." She describes her visions as a gift "for me to put my visions down on paper and show people." These visions continued as she grew. In one, she "saw the endless universe, its past and its future, and I was told that from now on I needed to get up very early and get ready for my mission." Inspiration has for Akiane always combined with close observation, an encyclopedic memory for the world she sees and touches, and a lot of hard work. In her own words: "The visions and dreams were very vivid and prolific during the first 10 years of my life. Then, they decreased, but morphed into something different — into intense feelings and sounds." Driven by an inner compulsion to communicate these ineffable inspirations in the only way she knew how - through painting - she willed herself to create from a very young age, to make her likenesses as real and authentic as possible. Akiane became known nationally and internationally for her beautifully detailed inspirational painting, even as a young girl. In one of her visions, she saw that "everyone was separating their own little world, but at the same time we were all connected." In Akiane's own words again: "I made a commitment to myself that I have to do this because I want people to know the message and to be themselves and to be inspired and creative somehow." She feels that her 'gift' has been given "for one reason only, to help others.”

Through the lives of these four people, we can readily understand that intuitive or inspirational knowledge, when coupled with specific knowledge and skills, and applied through determination and hard work, produced outcomes that in their own way improved the lives of their community, touched people with joy and happiness, boosted the life outcomes of the impoverished, and advanced human civilisation.

It would I think be entirely understandable to think that the people I have highlighted here as examples are in some way 'gifted' with abilities beyond the capacity of normal people. Viewing the bigger picture shows however that the opposite is the case: this kind of sensitivity and perception is available to us all, to varying degrees of capacity. We only think the 'inspired' are great because they have committed their life's energies into making their intuition a reality; into sharing their knowledge in ways that benefit others.

These three snippets of written accounts left by perfectly ordinary people - anonymously - demonstrate the validity of this point:

It was like my brain opened up to receive knowledge. Although in this plane of existence my brain is limited, the experience left me with a thirst for knowledge

I also seem to have a gift of knowledge that I can answer someone's question about a subject that I have never studied nor knew anything about

When I am involved in creative endeavor, I feel as if I'm accessing the same pool of knowledge I accessed during my experience. I sometimes feel as though I 'channel' when I'm composing music or writing stories.

Alan Garner's story is more than anything a vivid illustration of this point. There aren't a few perfect heroes who are blessed with a gift and then don't put a foot wrong while they energetically prosecute their grand plan to save humanity. This is make-believe. The reality is very different, and a lot messier. Inspirational or intuitive information may become available in ways that the unwitting recipient is unable to comprehend, or make sense of in the context of their lives. It may be so strange and outlandish to them that they may deny or suppress it. Cultural norms and expectations, pressure or prejudice, or else the weight of their prior theories of how the world should work, may make accommodating what happened to them extremely difficult. One's mundane existence and the busyness of how lives are may just get in the way and push opportunities for action into the background.

As a case in point, while this article was being written, I happened to have a conversation with a very technically oriented gentleman with a decidedly mechanistic worldview. He shared that on one occasion after he'd finished extensively modifying an item of equipment he'd accidentally powered it up the wrong way up, after which it wouldn't work. He'd obviously thought he'd blown the circuitry, and made his mind up to order a replacement - quite a costly exercise. That night, he'd had a dream in which he said it was shown to him the three very precise actions he needed to get the equipment working again. While obviously not knowing what to make of it he decided to try the information out to see what happened: to his amazement, he very quickly had everything up and working and in operational order. "What are we to make of that?" were his words to me afterwards.

A better known, but decidedly unexpected, example is that of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, who, in his 'A Free Man's Worship', wrote:

… we see, surrounding the narrow raft illumined by the flickering light of human comradeship, the dark ocean on whose rolling waves we toss for a brief hour; from the great night without, a chill blast breaks in upon our refuge; all the loneliness of humanity amid hostile forces is concentrated upon the individual soul, which must struggle alone, with what of courage it can command, against the whole weight of a universe that cares nothing for its hopes and fears.

Yet the same man had, just two years earlier, a few minutes of inspiration, during which "a sort of mystic illumination possessed me": "Having for years cared only for exactness and analysis, I found myself filled with semi mystical feeling about beauty … and with a desire almost as profound as that of the Buddha to find some philosophy which should make human life endurable."

Dealing with the weight of the implications of intuition or inspiration is thus by no means simple or straightforward.

For some, they may not wish to burden the beneficiaries of their work with their own interpretations of how the knowledge 'got there' in the first place, preferring instead to quietly illuminate their worlds in whatever way they can, in ways that make sense to the recipient, if they put a little effort in.

Born in 1934 to a practical and down to earth working family in Cheshire during a time when there was little in the way of health and social services, and growing up during the second world war, in which privation was a common experience, Alan Garner lost more than half of his primary-school years through serious illnesses – meningitis, simultaneous whooping cough and measles, pneumonia and pleurisy. "I was written off as dead three times," he said.

Confined to his bedroom for long periods of time, the boy Garner drifted close to the line dividing life and death, in meditative communion with his immediate surroundings. At times, "the sensation was that of sliding out of phase with the boy in the bed." Paradoxically for one so ill, his thinking was clearer, more conscious, than he had ever known before - in common with this unrelated short excerpt from another person's account: "My thoughts were not disparate, or disjointed ... it was as though my life existed now in this supreme high-level of consciousness."

Garner wrote that the process of 'sliding out of phase' needed conscious agency: "there was a profound engagement in the activity of making the bed-bound 'me' let go of me ... I would concentrate on the concentration of the 'me' concentrating. I thought of the thought of myself thinking. I observed the observer observing; until the observer was not the observed." This multi centered thinking process is experienced in common with others, like this example: "I experienced incidents from my life from my own point of view, second, from the point of view of whoever was with me, and third, from the point of view of a witness, a watcher of sorts, all simultaneously."

Garner's route to his intuitive vision was to his perception 'through' the ceiling of his room. The ceiling 'became' another world that he lived in: "There was a forest in the ceiling, with hills and clouds, and a road to the horizon ..."

The world of the ceiling was three-dimensional, objects were solid, visual perspectives true. I never ate or drank in the ceiling ... There was no wind, no climate, no heat, no cold, no time. The light came from no source and was shadowless, as neon; but before I knew neon. And everywhere, everybody, everything was white.

Calling to mind that these are subjective attempts to describe the ineffable, without a common reference point, this description is similar to that seen in many other similar accounts, like this one, of being "in a room that looked like the inside of a cloud out of an airplane window." Or this one: "‘everything is happening simultaneously and time is something that we somehow make up."

Being ill in bed as a young boy was as it turned out the gateway to another formative experience. A joy and consolation to him during this time was printed cartoon comics. The young Garner engaged with the pictures and action sequences, but the words didn't as yet have any meaning for him. Then, one time, the implications of those peculiar shapes in the speech bubbles made sense to him, in ways that at the same time massively enriched the story he was engaging with, and at the same time profoundly disturbing to him:

The moment of realising that I could read was indeed transformative and terrifying – and remained so. To be able to move thought through space and time in this way, to be able to communicate with other, unknown minds, is a wonder that has never left me.

There is a lot of subjective meaning packed into that second sentence: something that I will come back to when I wrap up.

There is one other facet of Garner's retelling of his childhood ill in bed that has a bearing on understanding the rationale for Garner keeping his rationale cryptic; one that also shall be returned to. In his words:

There was one terror in the ceiling; one motionless dread. Sometimes I would look up, and see no road, no forest, clouds or hills, but a plump little old woman with a circular face, hair parted down the middle and drawn to a tight bun, lips pursed, and small pebbled eyes. She sat wrapped in a shawl in a cane wheelchair and watched me. She was a waning moon; her head turned to the side, as if she had broken her neck. When I saw her, I knew that I could die. She must not enter the room, and I must not enter the ceiling. If I let her eyes blink, I should die ... She was my death, and I knew it.

My understanding on reading this passage is that for Garner, the little old woman represents an entire loss of the self, an annihilation of his entire identity and being. This, to Garner, is so terrifying a possibility that it cannot be allowed. His existential dread seems somehow to interdict at that moment the process of 'entering the ceiling' i.e. of engaging with a different level of perception. It seems as though 'sliding out of phase with himself' and encountering the ineffable was at that moment so overwhelming that he would be in danger of losing himself.

This existential dread is not so strange; indeed it is entirely understandable. I've written elsewhere that our fear of death underpins so much of what happens in contemporary societies and cultures, worldwide. The jarring thing here though is this: for most people, a period of extended perception like the ones Garnet experienced in childhood dramatically decrease or entirely remove their existential fears. They share expressions like "The most noticeable thing I felt on coming back was that I had no fear"; "I am no longer afraid of death", and "[D]eath became my favorite subject overnight." But, clearly, not for Garner. Again, I shall return to this point later.

As might be expected, these perceptual experiences had impacts on other parts of his life too, in formative ways, in ways that would matter for the mature author. Just a few miles away from the bedroom where he lay ill for so long was a significant geological feature, a steep escarpment in East Cheshire known locally as 'the Edge'. This sudden uplift from the plains stretching away westwards over the rest of the county gave the village of Alderley Edge, now known as a playground of the well-heeled and famous, its name.

On better days, the young Garner would cycle over there and climb into the rocks. Noticing the detail of the grain and structure of the rocks, he found he had the propensity to 'commune' with the rock itself; to lose himself in those very details.

I lost all sense of 'me' upon the hill. As with the ceiling, a barrier was down. But, perhaps because I was not weakened, fevered, paralysed, the result was different. I felt not that I entered a world, but that a world entered me ... I switched myself off. And the universe opened. I was shown a totality of space and time, a kaleidoscope of images expanding so quickly that they fragmented. There were too many, too fast for individual detail or recall.

Garner's 'kaleidoscope of images' seems consistent with the way in which some people report their 'life review' being like, when they recall details of what happened to them in earlier life, for example: "I was watching millions of the pictures of my life’s events, like a movie broken down into picture frames. All the little deeds, thoughts and moments upon moments, even the ones I forgot ever happened, they were all there."

This experience, as well as being impactful and meaningful for the way in which the mature Garner would formulate his stories, also imparted considerable strength and comfort to the younger Garner as he grappled with his illnesses. Writing later of this ineffable experience on the Edge, he said:

Yet despite the hurly-burly beyond words, when I partook of the hill and the hill partook of me, there was a calm, which childhood could not give. For if the child had been left with only a vision, if the 'me' had not been replaced by a truer sense of self, I do not know what would have happened. I do not know that I could have grown. With only a blind vision, I do not know that I could have survived.

It seems that this assurance and knowledge of his true self imparted the strength of character the young Garner needed to find ways of dealing with the many trials this period of his life had dealt him. Note well the implication of his acknowledgement that 'he' is more than just his body, while at the same time still in fear of his personal annihilation.

In addition to his dreams and visions, and his awakening love of reading then of literature, the other formative influence on the young Garner was the oral storytelling traditions imparted through his grandfather. I won't go into details here, but these stories, grounded as they were in the immediate landscape of the area, and in historical figures in his family, proved to be a very powerful influence on the way in which Garner would shape his inspirations into stories of his own to share with his readers.

There is one other particular noteworthy observation relating to one of these oral traditions that he absorbed when he was younger that is of significance, and that is his take on the implication of the fable of the 'sleeping king under the hill', of Arthurian connection. In Garner's words:

There are analogues for the sleeping hero, right across the northern hemisphere – I think there are nine in Britain alone. And the question that intrigued me was: Why, in every version, after the sleeper begins to awake, does the mortal who finds him say: ‘Sleep you on!’? The answer I’ve come up with is that it seems as though the sleeping hero is the last ace in our hand and while he’s asleep, he’s potential. Once we wake him, we’re finished.

The meaning Garner found that makes sense to him seems to me to be very revealing. There seems to be a necessity of maintaining a distance between finding the 'sleeping king', and actually waking him ... a distance by necessary analogy in my understanding of how Garner's mind works between encountering inspiration and fully acknowledging it. Again, this is an observation I shall return to.

On those occasions that Garner has shared something of the process of writing as he experiences it, his words make clear that for him this is a not a planned, systematic process. Here his explanation verges on the scatological:

And then another turd comes through. I know the pattern. I don't want to be mysterious about it. It's the unconscious mind delivering to my conscious mind. A little comes. Then there's a space. As time goes on, the spaces get shorter and the amounts get greater.

Garner acknowledges the critical role his love of literature, and his discipline borne of advanced studies of classics, has in this process. But for him, this is not foremost. Writing for him is "partially intellectual in its function, but is primarily intuitive and emotional in its execution."

Here again Garner draws a distinction between a purposeful and planned style of writing, and his own, which is intuitive:

In writing serious fiction, the writer is trying to understand and to communicate. And one way of doing that is what I would call the ‘observational’, which is concerned with the whole of human existence, its joys, its sorrows, its problems. And so you get Jane Austen.

The other way is not observational but visionary, and that’s far closer to dreaming. It is a poetic way of looking at the world, and it makes quite different demands on the writer. It has to be dragged out of the individual’s depths, the depths of the whole culture – the collective unconscious, if you accept the term – and therefore it’s far harder to do.

In reading his shared thoughts here, I feel it is particularly important to emphasise Garner's distinctive meaning of 'far closer to dreaming': in his words: "A dream is not unreality." For Garner, writing is "close to prayer."

Garner then applies the full force of his intellectual rigour and love of literature, through much discipline, dedication and hard work, to transform what would otherwise be the vaguely connected and not fully formed products of intuition acquired through his meditative state into a marketable final product that the reader can relate to.

As an example, in preparation for his 'Elidor' story, he

had to read extensively textbooks on physics, Celtic symbolism, unicorns, medieval watermarks, megalithic archaeology; study the writings of Jung; brush up my Plato; visit Avebury, Silbury and Coventry Cathedral; spend a lot of time with demolition gangs on slum clearance sites; and listen to the whole of Britten's War Requiem nearly every day.

Reflecting on the contribution his literary background had in this process, Garner said

I endured the rigours of an education that matched vision with thought, each to feed the other, so that dream and logic both had their place, both made sense, and legend and history could both be true.

I feel that over the past evenings preparing this article I have in a sense 'sat with' Garner and begun to really appreciate his intellectual humility, which I will here let speak for itself:

I feel it would be arrogant of me to say that I knew the truth.

[F]or me metaphor and myth are the purest way to begin to appreciate reality.

I like to think that what I write is an open hand, not a pointing finger. ‘Is there anything there?’, not ‘This is what it’s about.’

I greatly appreciate and indeed have huge admiration for him in that in this way he is consciously avoiding the fallacy of weak induction. He is for me in this way carefully avoiding the trap of imposing his interpretation of the way things are onto the reader. Partly because of a recognition that, before the ineffable, we are in the final analysis incapable. And partly because he wishes to avoid the baggage of being seen as some kind of 'enlightened sage':

I find myself avoiding that question [of the origins of Garner's intuition] because what I write sometimes attracts people who are not... entirely in balance. And to speak publicly about inner spiritual forces could be dangerous. There was a time when I was bombarded by people who saw me as some sort of John the Baptist figure; a sage. It would be hubris on my part if I were to encourage that, and very dangerous for others.

In summary, for me, Alan Garner's inspiration is cryptic because of two main reasons. First, because he exhibits that tender, precious humility that says 'I do not know, so I am not going to try to know'. And second, perhaps, because he fears deep within himself a loss of individuation - a death of the self - that would come with allowing the 'king under the hill' to arise and come forth.

These reasons are truly special to me because they speak - nay, fairly shout - the ordinariness and commonplace circumstance and nature of Alan Garner's inspiration. Fallible. Unclear. Muddling through. But doing the best we can, labouring under our life's burdens.

Garner, like us, while far from perfect, is capable.

Does the cryptic nature of Garner's inspiration mean that he is entirely unaware of his social mission? Actually, I am not convinced it does.

I saw that inner and outer worlds do not collide. I saw a unity at work outside myself.

I write in order to answer questions I can’t resolve intellectually.

These thoughts are expressed in a way that is centered on Garner himself. However, what he has done here is produced a volume of works that he has then shared with others. His perceptions, his questions, then become those he shares with others.

=================================================

Bibliography:

Wikipedia article on Alan Garner

BBC Culture article "Alan Garner, The magical master of British literature, 13th October 2022

Interview with Alan Garner in 'High Profiles' [highprofiles.info]

Chapter 1 of "The Voice That Thunders", by Alan Garner

Biography of Alan Garner in 'The Independent', 26th September 2010

Interview with Alan Garner appearing in 'The Guardian' 14th December 2024

About the Creator

Andrew Scott

Student scribbler

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.