"The Denial of Death", by Ernest Becker

One person's perspective

This is just one person's understanding of the Pulitzer Prize winning book "The Denial of Death", by Professor Ernest Becker. It is not meant to be authoritative, and nor is it meant to be a review of the book of any kind. The author is not a specialist in fields touched on by this book, but merely wishes to record a personal impression for later reference.

I think this is possibly one of the most under-rated books of all time. Certainly not because I think this book, or its author, have all the answers. Nor is it because I believe or agree with every word, nor indeed all of the ideas presented in its pages. Nevertheless I suggest it is of pivotal importance because the author says something of great significance, that is at the same time widely overlooked.

One might say, consciously - and studiously - ignored, because that something Professor Becker writes of is a taboo topic. Something indeed that our societies cover up with frenetic activity, with mounds of 'stuff', with endless distractions, with heroes, idols and icons. Much of what goes on in our cultures is driven by the deep-seated need to move the collective focus away from that question. Our civilisations lay waste to the world to forget, expend vast resources in our efforts to ignore the obvious.

We are going to die. All of us. No exceptions. Yet, we deny this fact. Run away from it. Tacitly agree to ignore it. Then deny that we did any of this, or that anything out of the ordinary happened.

Assuming the validity of our cultures' widespread assumptions about what makes a human being, then it can easily be seen that these defenses of denial - many-faceted; multi-layered; barely acknowledged - are absolutely essential to a person's continued functioning. Our 'forward motion', if you will. When these defenses break down or are no longer useful, or when we are denied access to the means of defending ourselves, the forward motion of our machinery (as it were) just stops. Breaks down, to continue the metaphor.

In this short article, I am going to touch upon some of the arguments in Professor Becker's "The Denial of Death", supported by some choice quotes from the book. I will then say a few words about how these arguments could be developed, extended and applied to our contemporary situation.

Before I do, I'd like to write a little about the man himself. Active in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, his lack of popularity among the authority figures of his day was matched by the boundless enthusiam for him among his young student base. He was renowned in particular for being an early pioneer of cross-discipline research and advocacy; ranging to include everything from cultural anthropology, through psychology, to the philosophy of religion.

Professor Ernest Becker himself passed away in 1973, before he could see the widespread admiration his magnum opus had attracted. In the first page of the Foreword in my copy of the 2020 Souvenir Press edition of this book, these words can be found:

The nearness of his death and the severe limits of his energy stripped away the impulse to chatter. We talked about death in the face of death; about evil in the presence of cancer. At the end of the day Ernest had no more energy, so there was no more time. We lingered awkwardly for a few minutes, because saying "goodbye" for the last time is hard and we both knew he would not live to see our conversation in print.

This touching interview, recorded when Professor Becker had just been admitted to hospital, and informed that on account of terminal cancer he had a week to live, was punctuated by these words from the man himself, spoken from his hospital bed:

"You are catching me in extremis. This is a test of everything I've written about death. And I've got a chance to show how one dies, the attitude one takes. Whether one does it in a dignified, manly way; what kind of thoughts one surrounds it with; how one accepts his death."

I am struck by three thoughts as I review what are to me these familiar words. First, the contrast of the passage written by the interviewer to the words of the interviewee is like that of a frightened ass before a lion. Second, how despite many shortcomings on account of being human, Professor Becker is here recorded really trying to live up to his ideals. And thirdly, the supreme irony of the juxtaposition of this text with that of the rest of the book it introduces.

In the remainder of this article, I am going to introduce and discuss some of the ideas Professor Becker introduces in his "Denial of Death". This is not meant to be a thorough or complete exposition: I've picked out a few of the themes that have struck me as insightful.

If Professor Becker could be called insightful, it is because he 'stands on the shoulders of giants'. His work could not be called particularly original; even the concept of the centrality of the fear of death in culture-building is not particularly new. Professor Becker is instead the master synthesiser: he brings all these ideas together, and marshals them all into a single progressive argument that in totality marks out his signal and most remembered contribution.

According to Becker, the "basic motivation for human behaviour" is "to deny the terror of death". For him, this terror reaches beyond the mere fact of our death ... he writes: "we are ultimately helpless and abandoned in a world where we are fated to die." Thereby the towering ocean wave of the enormity of this cruel world threatens to crash down upon us.

In contrast to on our animal side, for him this terror is a fundamental motivator for the creation of cultures and civilisations:

... the idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else; it is a mainspring of human activity – activity designed largely to avoid the fatality of death, to overcome it by denying in some way that it is the final destiny of for man.

It is this death avoidance that we see manifest in some of the most ordinary commonplace activities that surround us, and that we engage in ourselves:

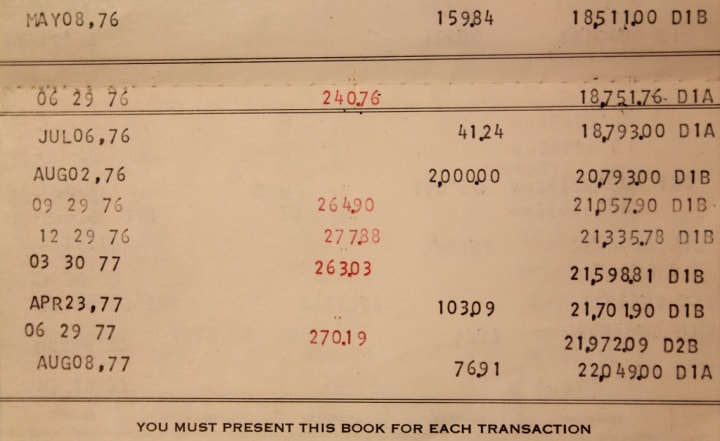

We disguise our struggle by piling up figures in a bank book to reflect privately our sense of heroic worth. Or by having only a little better home in the neighbourhood, a bigger car, brighter children.

This personal heroism is a theme that Becker touches on repeatedly in the book. For him, "heroism is first and foremost a reflect of the terror of death." Here, Becker doesn't mean literal mythical heroism of the tales of fables, but the perfectly ordinary heroism that we seek, according to him, to engage in to make sense of our place in the world.

This denied or repressed fear of death is, Becker writes, all pervasive - none of us are untouched by it:

… the fear of death is natural and is present in everyone, that it is the basic fear that influences all others, a fear from which no-one is immune, no matter how disguised it may be.

We adopt, with varying degrees of consciousness, certain patterns of thought and behaviour that are designed to defend or protect ourselves from the awfulness of the uncaring world and of our deaths. Becker's figurative man 'throws himself into action uncritically, unthinkingly' in a 'compulsive style of drivenness'; he 'accepts the cultural programming that turns his nose where he is supposed to look.' These learned techniques, which Becker calls 'character defenses', include not standing out; to put one's head above the parapet, as it were.

All of these defenses, this 'character armour' as it were, are all very well until they cease to function as they should; when we are 'prematurely startled into dumb awareness', as by war, pandemics, and the fate of our civilisation:

At times like this, when the awareness dawns that has always been blotted out by frenetic, ready-made activity, we see the transmutation of repression redistilled, so to speak, and the fear of death emerges in pure essence. This is why people have psychotic breaks when repression no longer works, when the forward momentum of activity is no longer possible

It surely doesn't need to be said that there are few better examples of the widespread 'psychotic breaks' consequent to the 'transmutation of repression redistilled' than the impacts of public health measures against the COVID-19 pandemic, when suddenly most of the means we had of distracting, disguising, refocusing away from our existential fears were made inaccessible.

For Becker, these fears, and all their concomitant defenses, are consequences of humanity's unique self-awareness and self-reflection. Animals 'are spared it': they 'live and disappear with the same thoughtlessness: a few minutes of fear, a few seconds of anguish; and it is all over.'

Humanity's unique self-reflective fear of death puts that fear in an entirely different category altogether from that felt by the animal. '[T]o live a whole lifetime with the fate of death, haunting one’s dreams and even the most sun-filled days – that’s something else.'

This fear of death, denied, that humanity alone suffers from is at once social as well as personal. According to Becker, we don't want to face up to the reality of our situation, 'clawing and gasping for breath in a universe beyond our ken'. Writing of his figurative man, Becker says (my emphasis):

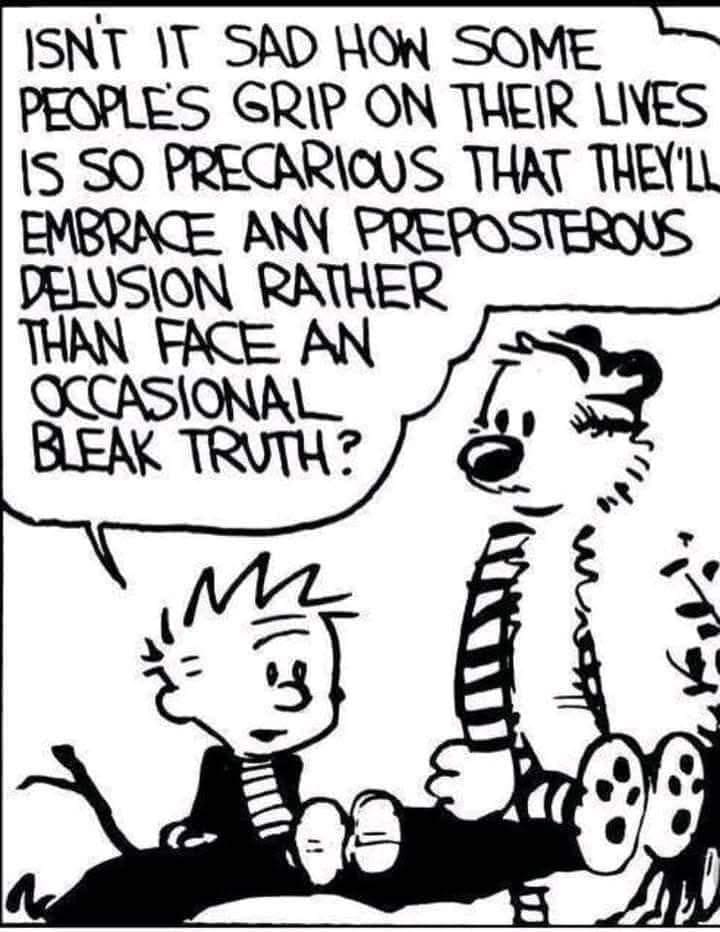

He literally drives himself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness – agreed madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.

At some level, according to this analysis, it all doesn't make sense, and we know it doesn't make sense, but we agree among ourselves to carry on as we are, because the consequences of publicly admitting that it doesn't make sense would be just too terrible.

Our 'character defenses' - both learned in childhood and culturally propagated - are according to Becker essential; the process of removing them either through introspection or psychoanalysis brings with it the fear of being 'torn apart, of losing control, of being shattered and disintegrated, even of being killed'. The act of diving into the dark maelstrom of our own fears necessarily then risks our very being itself.

It is these self-reflective defenses that amount to limitations that we impose on ourselves that prevent us from experiencing the full joy of life itself, because we shrink in horror from the experience of opening ourselves up to that degree. This is something that is otherwise known as the 'Jonah syndrome', well-known in Becker's day. In contrast to the 'tiny world' of the animal's experience, humanity, 'the impossible creature', is confronted by the terrible and appalling enormity of the universe itself: the crushing 'everythingness', as it were. So a person must as they grow into the world build defenses not only against their own expiration but also against the full experience of the world.

Becker call this the two great fears that animals are protected from: the fear of life and the fear of death, without truly appearing to realise that they are two sides of the same coin. We fear death out of ignorance of who we really are. And at the same time we shrink back from experiencing the fullness of life because we cower before a universe that seems to us to be uncaring. (I write as I do to offer a refreshing new perspective that regaining the knowledge of who we are at once releases us from the leaden weight of existential fear and at the same time enables us to connect with confidence with the world of other-than-us. Solving at a stroke both sides of this existential dilemma.)

One could say that the process of overcoming one's fear of death consequentially leads to also overcoming our fear of agency, of 'standing on our own two feet', and really maturing into our own destiny.

What, experientially, does it mean to us when our 'character defenses' are weakened or disabled through a programme of systematic introspection, or of psychoanalysis? Becker borrows a characterisation of these defenses as cocoon-like layers that we build upon ourselves; the first two of which being those of a comparatively trivial nature that we use to interact with the world and to build the way we wish to be seen by others. Underneath that is a hard shield that 'covers our feeling of being empty and lost'. This covers the final layer of existential fear, which covers in turn our 'authentic self'; the one without 'sham' or 'disguise' (original emphasis):

From this sketch of the complex rings of defense that compose our character, our neurotic shield that protects our pulsating vitality from the dread of truth, we can get some idea of the difficult and excruciatingly painful, all-or-nothing process that psychological re-birth is. And when it is through psychologically, it only begins humanly: the worst is not the death, but the rebirth itself—there's the rub. What does it mean “to be born again” for man? It means for the first time to be subjected to the terrifying paradox of the human condition, since one must be born not as a god, but as a man, or as a god-worm, or a god who shits. Only this time without the neurotic shield that hides the full ambiguity of one's life. And so we know that every authentic rebirth is a real ejection from paradise, as the lives of Tolstoy, Peguy, and others attest. It takes men of granite, men who were automatically powerful, “secure in their drivenness” we might say, and it makes them tremble, makes them cry.

The removal of our layers of character and existential defense - conscious or not - is a truly terrifying experience to be making in an unsupported environment. The vast majority of us are not at all equipped to undertake this process. The ejection from the 'paradise' of our self-delusion to witness the world-as-we-think-it-is is a realisation of the metaphorical hell on earth. This is the same regardless of whether one's defenses are weakened through lack of access to the means of distraction or refocus, or due to deliberate and self-conscious descent into our own existential fears.

Even supposing that psychotherapy could 'cure' our fear of death - which, according to Otto Rank (of whom Becker thought very highly) was impossible: it could not be overcome therapeutically "as it was impossible to stand up to the terror of one's condition without anxiety" - then one would constantly have to be on the lookout for retrogression:

It was Andras Angyal who got to the heart of the matter of psycho-therapeutic rebirth when he said that the neurotic who has had therapy is like a member of Alcoholics Anonymous: he can never take his cure for granted, and the best sign of the genuineness of that cure is that he lives with humility.

More so, presupposing our dominant culture's axioms of what makes a human being and how we relate to the world, removing a person's existential defenses has precious little to offer:

When you get a person to look at the sun as it bakes own on the daily carnage taking place on earth, the ridiculous accidents, the utter fragility of life, the powerlessness of those he thought most powerful – what comfort can you give him from a psychotherapeutic point of view?

Worse, according to Becker, is that this 'cure' would compromise our ability to function:

It can’t be overstressed, one final time, that to see the world as it really is is devastating and terrifying. It achieves the very result that the child has painfully built his character over the years in order to avoid: it makes routine, automatic, secure self-confident activity impossible.

The foregoing paragraphs paint a very bleak picture indeed. As one digs deeper into our defenses, in an effort to investigate and find a 'cure', one seems to reach the inescapable conclusion that our efforts are for naught: the 'cure' is worse than the cause. I suggest it would do well to remember that these conclusions are conditioned on accepting our dominant culture's take on what makes us human. Should reasons be found to challenge this dominant narrative, then this whole chain of reasoning becomes susceptible to transformation in unexpected ways.

Being 'fully human', according to Becker, means being able to access the full range of our experiences, and take in life as it is, rather than as we would wish it to be. But, according to Becker's analysis, we find this terrifying, and hence we prevent ourselves from living fully:

The irony of man’s condition is that the deepest need is to be free from the anxiety of death and annihilation; but it is life itself which awakens it, and so we must shrink from being fully alive.

Our lives then become constrained: painted in shades of a sepia-toned dull monochrome:

Man is protected by the secure and limited alternatives his society offers him, and if he does not look up from his path he can live out his life with a certain dull security.

It therefore becomes safer not to 'stick our heads above the parapet'; to kow-tow to the norms of our society.

... the “culturally normal” man, the one who dares not stand up for his own meanings because this means too much danger, too much exposure. Better not to be one-self, better to live tucked into others, embedded in a safe framework of social and cultural obligations and duties.

Becker's 'automatic cultural man' - his figurative man - is then "confined by culture, a slave to it, who imagines that he has an identity if he pays his insurance premium, that he has control of his life if he guns his sports car or works his electric toothbrush." It is surely not difficult to project this inauthentic figurative man - a slave to his culture - forwards to our current technology and fashions; one fashions an identity around different objects in the same way.

Assuming as Becker does through most of this book that death marks the end, that one is beset by the enormity of the cold uncaring universe, then being truly aware of one's condition is to know that the essence of who we are is 'food for worms':

This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die.

We defend ourselves against thoughts of our own mortality then by acquiring material possessions, by filling our hours with ceaseless activity, and by following along with the norms of our culture. Another defensive mechanism Becker introduces is hero or leader worship.

On the face of it one could simply stop the analysis at the level of power: we worship or fear power, hence give our loyalty to those who dispense it. While appearing logical and self-sufficient, this kind of shallow analysis is ultimately unsatisfying: it is susceptible to 'why' questions.

Becker illustrates the point by calling to mind the hundreds of thousands who willingly put themselves in the line of 'blistering gunfire' in World War I. Why would they do it? "The real world is simply too terrible to admit; it tells man that he is a small, trembling animal who will decay and die." The irony of these soldiers who stood up and climbed out of their trenches to die in droves is that they were doing so because they had transferred their wish for immortality to their leader, who seems heroic and capable of granting them this wish.

The object of one's transference of our immortality wish need not be human - it can be literally an object itself (e.g. a statue, a crown, a flag), or it can be a cultural symbol, for example the state, the party, the church. The property of transference remains the same: the object that one transfers our immortality wishes becomes invested with 'magical powers' to relieve or combat our death anxiety.

But be it a person, an object, or a symbol, what trouble may be caused when the transference object appears to become threatened! In the act of transferring our immortality wish to the 'object', we become bound to that object: it becomes an extension of the core of our own being.

Becker illustrates this point vividly in the instance of the transference object being a person, a leader. When the inevitable happens and the leader dies, the 'fantastic displays of grief' that become manifest are then understandable:

The uncontrolled emotional outpouring, the dazed masses standing huddled in the city squares sometimes for days on end, grown people grovelling hysterically and tearing at themselves, being trampled in the surge towards the coffin or funeral pyre – how are we to make sense out of such a massive, neurotic “vaudeville of despair”? In one way only; it shows a profound state of shock at losing one’s bulwark against death. The people apprehend, at some dumb level of their personality: "Our locus of power to control life and death can himself die; therefore our own immortality is in doubt." All the tears and all the tearing is after all for oneself, not for the passing of a great soul but for one's own imminent passing. Immediately men begin to rename city streets, squares, airports with the name of the dead man: it is ass though to declare that he will be immortalized physically by the society, in spite of his own physical death.

Such a leader-object need not be a military general, or a politician; they are just as often a significant cultural icon. Simply witness not only the 'Elvis never died, he lives on' movement, but also the (possibly less facile) example of the George Best Airport in Belfast.

When the leader dies the device that one has used to deny the terror of the world instantly breaks down; what is more natural, then, than to experience the very panic that has always threatened in the background.

This insight speaks to the issue of 'othering': in belonging to a group which identifies with a given transference-object, we make ourselves vulnerable through this extension of ourselves to the object to apparent threats from the 'out-group', from the 'other' of those who don't look like us, don't speak like we do, don't dress like us. Remembering that this object can also be a cultural icon or idea, this would extend to 'our' political party, 'our' state, 'our' religion. A perceived threat - sometimes from the very existence of the 'other' - brings up in us the strongest reactions that defy rationality. Hence the seat of the 'dogmatic' or 'doctrinal' response ... here, appeals to reason won't work.

The character defenses we have built up against our mortality have consequences for the world we live in too, as could be expected. We hide our fear of death behind a 'massive wall of repressions'; these defenses are multiplied through the prevalence and commonplace nature of these defenses:

... all through history it is the “normal, average men” who, like locusts, have laid waste to the world in order to forget themselves.

If the consequences of our character defenses against our own mortality are so terrible, then surely the obvious solution is to abolish death altogether through the extension of life? This is the project of the various life-extension movements in their dizzying array of variety:

We can envisage a utopia wherein people will have such long lives that the fear of death will drop away, and with it the fiendish drivenness that has haunted man so humiliatingly and destructively all through his history and now promises to bring him total self-defeat. Men will then be able to live in an “eternal now” of pure pleasure and peace, become truly the godlike creatures that they have the potential to be.

The fly in the ointment here however, "a caution to this vision that goes right to the heart of it and demolishes it", is one of accidental death. Not just the fact of it, but the magnification of the threat of it, and the impact that magnification would have on our defenses would themselves be grossly multiplied:

The smallest virus or the stupidest accident would deprive a man not of 90 years but of 900 – and would then be 10 times more absurd. … If something is 10 times more absurd it is 10 times more threatening. In other words … men in the utopia of longevity would be even less expansive and peaceful than they are today!

The people of such a 'utopia' would be even more fearful of their mortality than they are today, because they have so much more to lose.

In this article I have picked out only some of the essential themes that weave through the book; I believe though I have extracted the most essential - and the most enduring - parts of his message, that are not otherwise contingent on domain specialism or on now discredited patterns of thought.

It is worth repeating that the efficacy and the verisimilitude of Becker's thesis rests upon the central conception of human nature common in our dominant culture - worldwide. Namely, that we are helpless slaves to the 'human condition', and equally helpless in the final analysis to improve our lot. So, then, the only thing to be done is to understand our deepest fears, and predict the ways in which we most often respond, individually and collectively, to differing stimuli.

This kind of thinking is commonly manifest in fields as diverse as advertising and identity politics. Behind all the messaging the psychological theory is very much the same. Becker's work casts much longer shadows into our contemporary universes than is commonly realised.

Challenging - with reason, and with evidence - the basic assumptions about human nature that drive Becker's thesis is at the heart of my discourse. I have written more about transference in its various guises; about the links between our fear of death and climate doomerism; about some of the reasons behind our fascination with aliens and artificial intelligence; and about why we live for the now rather than plan intelligently for the future.

There will I have no doubt be other articles that reference this one.

However, for me, the reason I find Becker's work so illuminating and under-rated is not - as I said earlier - because I think he has a solution, but because he has his finger on the pulse, diagnosing the ills of our modern societies.

About the Creator

Andrew Scott

Student scribbler

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.