Among Tin and Shared Dreams: Life in the "Conventillos" of La Boca

The Tin Houses: The Ingenuity of Immigrants

I was born in Buenos Aires, but I have been living in Turin, Italy, for six years. Today I can say, with my heart in my hand, that I know what it means to be an immigrant: the obstacles, the sadness, the joys… and, of course, the dreams that live in the soul.

That’s why, when I returned to visit my country, one of the first places I wanted to explore was the colorful neighborhood of "La Boca". Famous for its football team, yes, but for me, it was much more than that. Walking its streets again made me see it with different eyes, with the sensitivity that only time and distance can give. And then I asked myself:

What must life have been like for those early immigrants of the La Boca neighborhood?

I began my walk at the Plazoleta de los Bomberos Voluntarios in La Boca, at the corner of Garibaldi and Gral. Gregorio Araoz de Lamadrid streets, from where you can reach, just a few meters away, the famous pedestrian walkway and open-air museum, "Caminito".

Few places in Buenos Aires capture the spirit of the city as well as La Boca. Its streets, painted with a vibrant palette of yellows, blues, reds, and greens, look like a living postcard pulsing to the rhythm of tango and the river. But behind this explosion of color lies a deeply human story, forged through the work of immigrants, the murmur of the Riachuelo River, and the boundless popular creativity that gave identity to an entire neighborhood.

Walking through this cheerful passage, one can step back in time and imagine the neighborhood at the end of the 19th century. At that time, La Boca had become home to thousands of immigrants, mostly Genoese, who arrived with dreams and hopes, seeking work in the shipyards and slaughterhouses port adapting to a new and challenging place.". With limited resources but infinite creativity, they built their homes with whatever they had on hand: wood, iron, and metal sheets salvaged from ships and warehouses.

The wavy walls, so photogenic today, were born out of necessity and ingenuity. Each metal sheet was cut, hammered, and adapted again and again, until it formed a home that protected its inhabitants from the wind, the rain… and the uncertainty of starting from scratch. These houses tell stories of effort, resilience, and shared dreams, which still pulse in every corner of the neighborhood.

Many of the city tours offered in the city include a stop to explore the emblematic neighborhood of La Boca, which today attracts thousands of tourists.

The vibrant colors of this place originally had a practical purpose. Genoese sailors used leftover naval paint to decorate their homes, but since a single color was never enough to cover an entire façade, each wall ended up a different color.

Unintentionally, they created a unique aesthetic: an improvised symphony of colors that became the very identity of the neighborhood.

This narrow passage, now filled with murals, tango couples, and tourists with cameras in hand, was once an old railway line. Decades later, the painter Benito Quinquela Martín, a son of the neighborhood, transformed it into what we now know as Caminito.

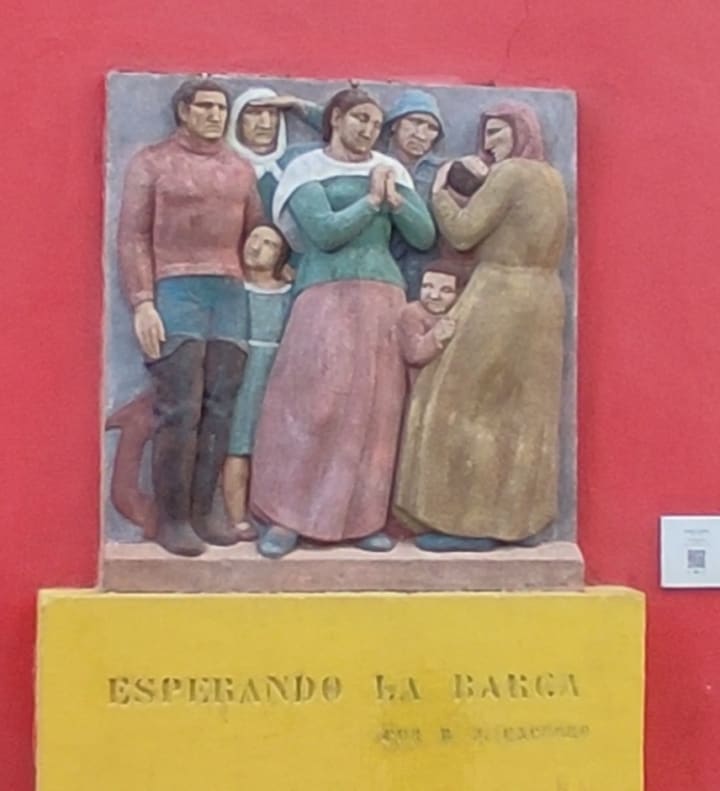

There, you can admire several works, but from my point of view, “Esperando La Barca” by Roberto Capurro is one of the pieces that best represents the hope of those waiting for news from across the ocean. These were immigrants who had left their homeland in pursuit of their dreams. Observing it offers a moment of reflection on the past that shaped the soul of La Boca.

These men and women began arriving in the neighborhood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as La Boca was one of the main points of entry for those landing in Buenos Aires. Most were Italian, accompanied in smaller numbers by Spaniards and some French, which is why the neighborhood became known as “La Piccola Italia.”

On Magallanes Street, parallel to the Caminito passage, stands the "Centro Cultural de los Artistas", a vivid reflection of what life was like for these newly arrived immigrants.

Interestingly, the buildings were not constructed from scratch. They were originally large houses belonging to wealthy families who, after the yellow fever epidemic of 1871, moved to the northern part of the city. With the arrival of new waves of immigrants, these houses were subdivided and rented out, giving rise to the so-called “Conventillos.”

The former rooms, designed for a single person, began to house entire families. A house that had been built for just one family now accommodated several. In this way, what were once spacious homes transformed into small universes of community life, where families shared not only space but stories, dreams, and resilience.

In these conventillos, each room served as a home for one family, while the courtyards became kitchens, laundries, and gathering spaces. Among the echoes of laughter and the aromas of home-cooked meals, daily life revolved around work at the port, household chores, and small celebrations held in the patios. Parties, tango, and popular music became their outlet — a way to keep their traditions alive and their spirits strong.

Continuing my walk, just a few steps away I reached another magnificent spot where it’s impossible not to feel as if you’ve stepped into a time machine — imagining the place buzzing with the arrival of thousands of people carrying suitcases and speaking different languages — Italian, Genoese, Spanish — from which later emerged lunfardo, the unique Buenos Aires slang still heard in the city today.

This place is La Vuelta de Rocha, an old port and dock located in La Boca, along the banks of the Riachuelo River. It once served as a key point for the arrival and departure of goods and ships.

In its early days, it was used to load and unload products, mainly connected to the shipyards, slaughterhouses, and warehouses of the neighborhood. Over time, although it lost its original port function, La Vuelta de Rocha became a historic site — a witness to the birth of La Boca as a neighborhood of hard work, culture, and popular creativity.

After visiting the riverbank, I took Dr. del Valle Iberlucea Street until I reached the emblematic Boca Juniors Stadium, better known as La Bombonera.

Walking along this street, it’s impossible not to notice the blue and yellow colors flooding the façades, murals, and jerseys — the colors of the famous football club Boca Juniors.

Curiously, in 1905, when the club was founded, the first members decided that its official colors would be those of the first ship to enter the port. That ship came from Sweden, and since then, blue and yellow have not only represented the club but have also become enduring symbols of the neighborhood, its people, and its rich portside history.

Walking through La Boca is to feel how the past and present intertwine — and to understand why this corner of Buenos Aires remains a symbol of art, culture, and popular life that continues to inspire everyone who discovers it.

About the Creator

Tati Asencio

I enjoy writing. I love sharing stories that live in the streets and in people. Some move you, others surprise you; but all come from the soul.

Thanks for joining me on this journey.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.