A Plain Wooden Shrine

Questioning the authentic Japanese experience

When Abe took office, tourism to Japan found a place of prominence on the agenda, governmental interests seeking to open up Japan as it was ‘opened’ up in the time of the Meiji Restoration. In the tradition of such writers as Louis Theroux, the ‘real traveller’ would lament increased tourist traffic for economic gain. As if crossing paths so easily with another foreigner would somehow taint the purity of the place — the authenticity diluted by commerce and by all those who had looked upon it before. An unchangeable permanence, as Frow puts it, the nostalgia of semiotics, signs of culture outside of ourselves. Things that seem simple and pure, only because we don’t understand them—the grandeur of age, immortality, things that last lifetimes, things untouched by the ugly worlds of corruption and the vapid, hollowness of disposable consumer goods.

My friend and I took a two day trip, on the back of our international exchange in Osaka, to the coastal town of Ise. My friend had chosen our destination on suggestion from a friend — I was just happy to see the ocean. Upon our arrival we rented bikes and like any good tourist, visited the most popular attraction in the area, two of Japan’s most sacred and important Shinto Shrines. My friend acted as guide, speaking from the pamphlet as we walked the deeply shaded grounds of the first shrine, along wide gravel paths. Large trees were wrapped with thin, aged rope, making the presence of Kami, or spirit, within visually significant aspects of nature.

Worshippers threw coins in the river, they washed their hands and mouths, purifying themselves before casting their prayers into the ether, clapping their hands in front of simple wooden shrines positioned on small hill tops. My friend received a stamp in her collector’s book for 300 yen. I never grew tired of seeing the monk’s deft calligraphy, accompanying the beautifully carved ink impressions. My friend would grumble if the monk wrote the date in English, ruining the complete aesthetic of her fold out book.

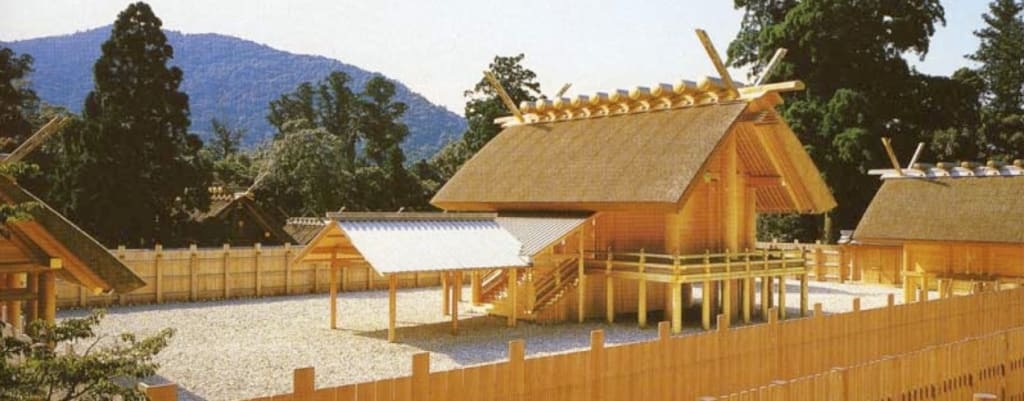

We rode our bikes to the sister shrine, almost identical. We bowed under the massive tori gate and crossed the bridge—wooden, with thick railings, smooth to the touch. The shrines were the same pale wood, the kind that, back home, would be stained darker or painted to hide the plainness of the timber. Here it was left bare, looking incomplete. The shrines were rebuilt every 20 years. We offered a coin and prayed, unable to see the full shrine behind the tall, slatted walls. A monk, in white robes, led a group of middle aged Japanese men in suits through a ritual and then into the shrine.

I stood and stared at two smaller shrines, side by side. The new that would soon replace the old—covered in moss and blackened mould, its thatched roof frayed and rotting away. The new that in 20 years would suffer the same fate. I wasn’t quite sure why I was so let down by this plain, ordinary wooden shrine. Did it shatter my illusion of Japan? The beauty of age, the ancient mystery? Shinto preceded Buddhism in Japan. Those beautiful adorned temples, with the impossible towering Buddhas, weren’t always so accepted. If Shinto was the original spirit of Japan, every Buddhist temple and shrine I so admired felt like a foreign intruder. Yet nothing was more iconographic than the Todaiji in Nara or Byodo-in temple in Uji, the mark on the 10 yen coin. Change. The structures had burned down, been rebuilt and were subject to constant renovation. Anyone looking for some untouched original symbol of Japan would be at a loss. The ideal was pointless. The immortal, traditional, authentic image was a distraction from the truth. Nothing is constant except change. Nothing is a pure receptacle of culture, not that the traveller can reach. So should this ideal be so prized among the travelling community? Authenticity in culture can sometimes be expressed as a fear of change. An effort to preserve culture can lead to the exclusion of others. As if the mere presence of foreignness dilutes its essence. The only threat to culture comes from within. In present day Japan it isn’t taken by force, or repressed by tourism and immigration. It carries on, shared and appreciated amongst the many.

While in Japan, I visited the Kinkoku-ji, the golden temple of Mishima’s famous novel. If I had never read that book, I would have never known that this glorious iconic temple was burnt to the ground not but 70 years ago. It isn’t change itself, but fear of change, not the loss of culture, but the fear of losing that culture that irks the traditionalist in all of us. And just as Japan holds onto the ideal Japan, so do those who travel there. However, the dilution of Japanese culture isn't something to be lamented, as according to Greg Sheridan, Japan modernised in a way where it was able to maintain its collective spirit and plot the course of its own progression. Just as Buddhism was embraced by Japan, Western consumerism become subsumed by the Japanese culture, until Starbucks and 24 hour convenience stores became just another part of the Japanese experience, and somehow, to me, less out of place than a plain, wooden Shinto Shrine.

About the Creator

Abbey Hunt

An aspiring author writing short stories/series in fantasy, speculative, romance, adventure, or slice of life, and the odd philosophical take on movies or TV series. Love to share the joy and light of creative expression.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.