The Psychology of Stock Market Crashes

Understanding the Emotions, Biases, and Behaviors That Drive Financial Panic and Recovery

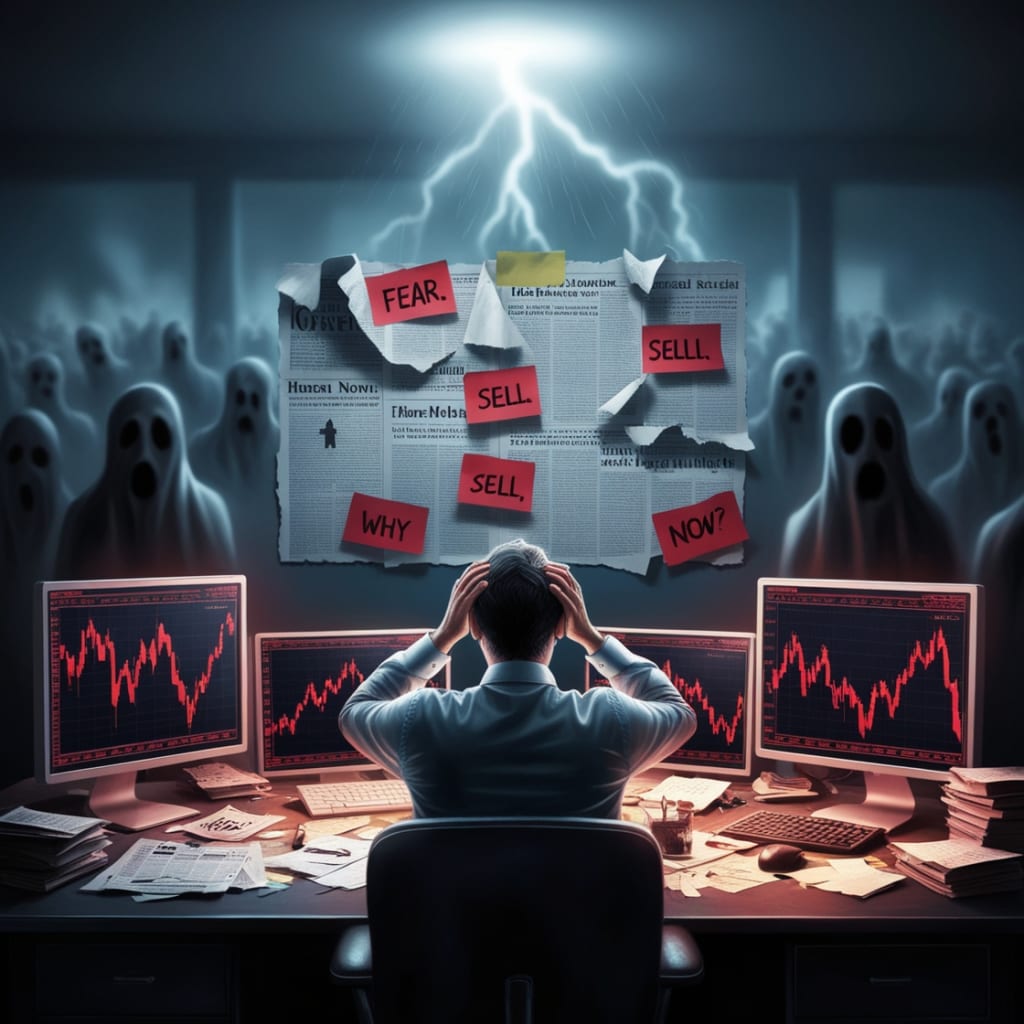

Few things in economics stir as much fear and fascination as a stock market crash. To some, it's a sudden and devastating loss of wealth. To others, it's an opportunity cloaked in risk. But behind every chart that plunges and headline that screams panic lies something deeper: the human mind. The psychology of stock market crashes isn’t just about numbers—it’s about behavior, emotion, memory, and the power of collective belief.

A stock market crash is usually defined as a rapid and often unexpected drop in stock prices, typically over a few days or weeks. But while analysts often focus on technical indicators, interest rates, and economic data, it’s important to realize that markets are ultimately powered by people. Traders, investors, institutions—everyone makes decisions based on both rational models and emotional impulses. And when fear or greed dominates reason, the results can be catastrophic.

The roots of financial panic run deep into human psychology. Take, for instance, the concept of herd behavior—a tendency hardwired into us from prehistoric times. In early human society, following the group often meant survival. If everyone was running from danger, you did the same—no time to stop and analyze. Today, in the digital age, that same instinct plays out when investors rush to sell stocks simply because others are doing so. We don’t want to be left behind. We don’t want to be the last one holding a falling asset.

During a market crash, the emotional brain—particularly the amygdala—takes over. This part of the brain governs fear and quick reactions. Logical thinking, handled by the prefrontal cortex, often gets sidelined. You can see this clearly during events like the 2008 global financial crisis. In the span of a few months, rational portfolios were liquidated, savings wiped out, and many investors fled the market, not because of deep economic analysis, but out of sheer fear. The thought was simple: get out before it gets worse.

Another key psychological element is loss aversion. Coined by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, this concept refers to the idea that people feel the pain of losses more intensely than the pleasure of equivalent gains. In the context of a crash, this means investors often sell in panic to avoid further pain—even when doing so locks in losses. It’s why someone may hold on during moderate dips but eventually capitulate when the downturn deepens, only to miss the rebound later.

Interestingly, overconfidence also plays a role—especially before a crash. During boom periods, investors often believe that the good times will continue forever. The housing bubble in the mid-2000s is a classic example. Many investors thought real estate prices could never fall nationwide. That belief, unchecked, led to risky behavior, inflated asset prices, and eventually, a dramatic correction. In psychology, this tendency is known as confirmation bias—seeking out information that supports our existing beliefs while ignoring evidence to the contrary.

Then there's recency bias, where recent experiences carry more weight in our decision-making. If the market has gone up for months or years, we start to believe that it will continue to go up. We anchor our expectations in the near past. This bias often fuels bubbles—and then amplifies panic when the market suddenly shifts direction.

The psychology of stock market crashes is not only individual but collective. This is where the concept of social contagion comes in. Emotions, especially fear, spread like wildfire in groups. One person's panic can quickly become a group’s panic, especially in our hyper-connected digital age. With the rise of social media, forums, and 24/7 news coverage, investor sentiment can change dramatically in hours or even minutes. When enough people believe a crash is coming, their actions often help bring it about—a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Historical crashes reflect these psychological patterns. The 1929 crash was fueled by speculative mania, massive margin buying, and a collective belief in endless growth—followed by blind panic. In 1987’s “Black Monday,” program trading and computerized strategies added fuel to emotional decision-making, causing the Dow Jones to drop over 22% in a single day. Even the COVID-19 crash in early 2020 was driven as much by uncertainty and fear of the unknown as it was by concrete economic data.

Yet, the story doesn’t end with panic. Crashes are followed—sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly—by recovery. And that, too, involves psychology. As fear recedes, regret and hope creep in. Some investors begin to re-enter the market, driven by a fear of missing out (FOMO). Others remain frozen, haunted by the losses. Recovery requires a psychological shift: from fear to acceptance, from uncertainty to resilience.

For long-term investors, understanding the psychology of stock market crashes offers a form of defense. Knowing that panic, herd behavior, and loss aversion are natural reactions can help us resist them. Staying grounded in long-term goals, using tools like dollar-cost averaging, and maintaining a diversified portfolio are all strategies that act as emotional buffers during downturns.

Moreover, some of the world’s most successful investors have learned to harness this psychology. Warren Buffett famously said, “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” What he meant wasn’t about recklessness—it was about understanding human nature. Crashes often present opportunities, precisely because so many people are acting irrationally.

So, how do we prepare ourselves mentally for the next crash? First, we must accept volatility as part of investing. Markets go up and down—it’s the nature of the game. Second, we must educate ourselves about behavioral finance, not just technical analysis. Recognizing when we’re falling into patterns like herd mentality or recency bias is the first step toward making wiser decisions. And finally, we must cultivate emotional discipline—through mindfulness, planning, or even financial therapy. In the end, managing our reactions may be more important than managing our assets.

The psychology of stock market crashes is a mirror. It reflects back our fears, hopes, and deeply ingrained cognitive patterns. But it also offers a map—for those willing to look beneath the numbers—to navigate chaos with wisdom. Crashes are not just economic events. They are psychological storms. And like all storms, they pass—but only those prepared will emerge stronger.

About the Creator

Muhammad Asim

Welcome to my space. I share engaging stories across topics like lifestyle, science, tech, and motivation—content that informs, inspires, and connects people from around the world. Let’s explore together!

Comments (1)

Mr Market is an unpredictable beast. Just invest in good businesses and avoid turning paper losses into actual ones.