What Are the Global Implications of Russia and Ukraine Not Renewing Their Natural Gas Transit Agreement?

The U.S. remains one of the biggest beneficiaries. China is poised to continue benefiting. The primary losers are Europe and Ukraine.

Background:

On January 1, Russian energy giant Gazprom announced that it had ceased natural gas transit via Ukraine as the transit agreement between the two countries had expired. As of 8:00 a.m. Moscow time, Gazprom no longer possesses the technical or legal conditions necessary to export gas to Europe through Ukraine.

Similarly, Ukraine’s Ministry of Energy confirmed that it had stopped transiting Russian gas as of 7:00 a.m. Kyiv time (8:00 a.m. Moscow time) for national security reasons. Ukraine has notified its international partners about this decision.

The five-year natural gas transit agreement between Russia and Ukraine, brokered by the European Union in 2019, officially expired on December 31, 2024. In recent months, Ukraine has repeatedly stated its intention to halt transit and not renew the agreement.

This development, combined with the approach of a cold spell, has led to a 5% increase in European natural gas benchmark prices. On Tuesday, Dutch TTF natural gas futures for the nearest month exceeded €50 per megawatt-hour for the first time since late November 2024.

Meanwhile, according to the BBC, Ukraine’s largest private energy company, DTEK, confirmed that it had received its first shipment of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) on December 31, 2024. The shipment, totaling approximately 100 million cubic meters, was received at a Greek port on December 27, re-gasified, and transported to Ukraine.

This shipment follows a supply agreement signed in June 2024 between DTEK and U.S.-based Venture Global LNG. This contract represents the first major LNG agreement between the U.S. and Ukraine, allowing Ukraine to purchase unspecified quantities of LNG from Venture Global through 2026.

What Are the Global Implications?

The Acceleration of Global Energy Supply Chain Restructuring

From a macro perspective, the recent developments have significantly accelerated the restructuring of the global energy supply chain. The world’s leading oil and gas producers are the United States, Russia, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), with the U.S. ranking first, the GCC second, and Russia third. The traditional notion of the Middle East, or OPEC, as the dominant energy supplier is increasingly challenged due to uncertainties primarily caused by Iran and Iraq.

We set aside logic and focus solely on a phenomenon-based observation. Historically, when global energy supply exceeds demand, instability often arises in the Middle East. This is due to either internal conflicts or external intervention involving one or more Middle Eastern countries. The reason for this regional focus lies in the export-oriented nature of the Middle East’s energy production.

While the U.S. and Russia are among the top three energy producers globally, their energy exports are relatively limited. The U.S., for example, has only recently become an energy exporter, focusing primarily on natural gas. Russia exports slightly over a quarter of its production. In contrast, the GCC holds a dominant share of the global energy market, despite a gradual decline in this share.

The 21st century has seen dramatic shifts in global energy dynamics:

1. The U.S. Transition: The U.S. has transitioned from being the world’s largest energy importer to becoming a significant exporter, particularly of natural gas.

2. China’s Emergence: China has become the world’s largest energy importer, significantly shaping global demand.

3. Russia’s Resurgence: Russia has restored its production capacity, positioning itself as a major supplier.

4. Volatility in Other Regions: While other regions show substantial potential, their production remains inconsistent and unstable.

These factors have led to a significant restructuring of global energy supply chains.

The U.S. has played a central role in reshaping global energy markets:

• Iraq: The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq disrupted one of the world’s top four energy exporters.

• Iran: Sanctions on Iran have reduced its export capacity by two-thirds, severely limiting its role in global energy markets.

• Other Nations: Countries like Libya, Sudan, and Venezuela have faced persistent instability, preventing them from realizing their energy export potential.

During this period, China’s energy imports surged, reaching an oil and gas equivalent of approximately 700 million tons annually. This increase effectively absorbed most of the world’s production growth, excluding contributions from the U.S. and Russia.

The Emerging Question: Where Do U.S. and Russian Exports Growth Go?

With China’s growth consuming much of the global supply, the remaining market for increased U.S. and Russian exports is Europe. This shift explains several geopolitical moves:

• The U.K.’s Role: The U.K. has taken a leading role in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, leveraging its North Sea oil and gas production to secure economic benefits.

• U.S. Interests: The U.S. has provided substantial support in the conflict, as it stands to gain the most from supplying Europe with its growing oil and gas output.

The restructuring of the global energy supply chain is accelerating, driven by shifts in production and consumption patterns, as well as geopolitical strategies. The U.S. and Russia are capitalizing on Europe’s growing demand, while the Middle East’s traditional dominance is being challenged by internal and external factors. These dynamics highlight the complex interplay between energy supply, geopolitics, and market evolution in today’s world.

The Local Impact: Europe’s Energy Shift and Its Consequences

It seems likely that the U.S. has conducted systematic assessments of Russia’s economic resilience. Now, the strategy appears to involve systematically cutting off all external economic sources for Russia, even at the expense of allied interests.

If oil prices drop from over $70 to around $50 per barrel in 2025, it would be a clear indication that the U.S. is deliberately targeting Russia’s economic lifeline. Currently, Russia’s economy heavily depends on two major energy exports: oil and natural gas. With the natural gas sector already crippled, oil becomes Russia’s primary lifeline.

Russia’s economic situation is increasingly precarious:

1. Gold Reserves Depleted: Over half of Russia’s gold reserves have reportedly been consumed, signaling mounting financial pressures.

2. Inflation and Fiscal Stress: Domestically, inflation is rising, and fiscal constraints are becoming more acute.

3. Military Stalemate: The Russia-Ukraine battlefield is showing signs of stagnation, further straining resources.

There are several geopolitical complications compound Russia’s challenges:

• Syria: The situation in Syria, a longstanding Russian ally, is deteriorating.

• Belarus: The January 2025 elections in Belarus could bring additional instability to Russia’s sphere of influence.

• Internal Challenges: Chechnya’s increased assertiveness, highlighted by allegations that Chechen forces may have downed an Azerbaijani aircraft, showcases internal fractures. Since the Wagner Group purge, Putin has seemingly allowed greater leniency toward Chechnya, potentially creating further risks.

History offers a stark warning:

• Soviet Collapse: The Soviet Union disintegrated after a nine-year war in Afghanistan. In contrast, the U.S. maintained a 20-year presence in Afghanistan.

• Current Russian Stability: The current Russian regime, particularly the Siloviki (security and military elite), lacks the domestic control and mobilization capacity of the Soviet Union. Maintaining the Ukraine war for six to seven years would be an extraordinary challenge.

The ongoing war has already caused a significant brain drain and economic disruption in Russia:

• Talent Exodus: Hundreds of thousands of skilled workers, including engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs, have fled the country. For example, Yandex lost 400 engineers to Europe.

• Industrial Decline: Non-profitable innovation companies are failing, while many businesses face bankruptcy.

• Militarization of the Workforce: With so many individuals being drafted into military service, Russia’s economy is becoming increasingly one-dimensional.

If the war continues without resolution, the implications for Russia and Putin could be severe:

• Economic Disintegration: Further sanctions, particularly on energy exports, could lead to economic collapse.

• Eroding Political Authority: Mounting domestic challenges could undermine Putin’s political credibility.

• Potential Negotiations: A prolonged conflict might force Russia to consider peace talks, as continued warfare may prove unsustainable both economically and politically.

Moreover, Russia’s decision to halt natural gas transit through Ukraine to Europe might seem abrupt, but in reality, Europe has been preparing for this scenario for some time. The response? Cozying up to the U.S. and shifting to its “nobler” energy supplies.

From Russian Gas to American “Freedom Gas”

While Russian natural gas was affordable, it lacked the “aristocratic flair” that Europe seems to value. In contrast, U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) is pricier but imbued with the allure of freedom and quality. To Europe, it’s not just fuel—it’s a statement. Even the aroma of a cooked meal might carry an extra touch of liberty.

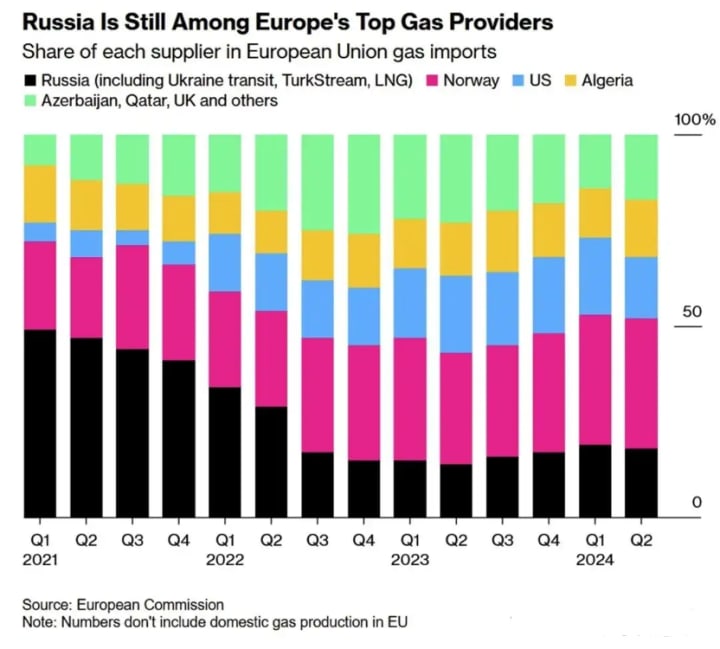

The European Union has exuded confidence, claiming its gas infrastructure is “resilient and flexible.” Since 2022, Europe has been systematically reducing its reliance on Russian gas, slashing the dependency rate from over 40% in 2021 to less than 10% by 2023. Clearly, Europe’s leaders are willing to pay a premium for their energy independence.

However, Eastern European countries, still wistful for cheap Russian gas, are left with no choice but to adapt to the new energy reality.

Turkey’s Windfall and Ukraine’s Misstep

Turkey, acting as an intermediary, stands to profit handsomely. Starting January 1, 2025, Europe’s only pipeline option for Russian gas is the “Balkan Stream,” an extension of the “Turk Stream” pipeline. This route supplies about 140–150 billion cubic meters of gas annually to countries like Romania and Greece.

Ukraine, on the other hand, finds itself on the losing side. Previously, it benefited from transit fees and sometimes siphoned off gas from Russian pipelines. Now, it has lost both revenue and access. For Russia, the economic loss from this pipeline shutdown is offset by newfound freedom from EU “political blackmail.” Without reliance on Ukrainian transit, Russia can escalate its attacks on Ukraine’s energy and industrial infrastructure without restraint.

This development allows Russia to pivot fully toward China. The severance of gas ties with Europe could symbolize a major realignment of Russian energy policy.

The reconfiguration of Europe’s gas supply is anything but simple. While the EU claims it has the infrastructure to replace Russian gas with alternative sources, transitioning suppliers involves significant time, cost, and potential supply instability.

Countries like Slovakia and other Central and Eastern European nations are particularly vulnerable. Energy prices are already soaring. Analysts estimate that Ukraine’s move could add an additional €51 billion in gas costs and €77 billion in electricity expenses for Europe over the next two years.

Higher energy prices will inevitably raise production costs for businesses, diminishing competitiveness and potentially stoking inflation. This could undermine the European Central Bank’s monetary easing policies, posing a serious challenge to the continent’s economic recovery.

Europe emerges as one of the biggest casualties of the Russia-Ukraine war. Meanwhile, the U.S., often seen as the “puppet master” behind Europe’s energy shift, is grinning ear to ear. The U.S. has long sought to reduce Europe’s dependence on cheap Russian gas, thereby increasing its reliance on American energy and bolstering its geopolitical influence. However, this comes at the cost of Europe’s economic competitiveness, driving the region closer to economic stagnation.

Faced with this new reality, Europe has no choice but to press forward, albeit with considerable difficulty. Whether Europe’s leaders can navigate these challenges effectively remains to be seen.

What is clear, however, is that the energy game is far from over. The long-term implications of this geopolitical and economic shift will continue to unfold, with Europe and its allies needing to adapt to a rapidly changing energy landscape.

Another Angle: Russia, Europe, and the U.S. in the Energy Puzzle

Despite Europe’s efforts to reduce reliance on Russian energy after the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Russia still supplies about a quarter of Europe’s natural gas. However, the supply gap left by Russia’s decline has largely been filled by Norway and, notably, the United States.

Who’s Filling the Gap?

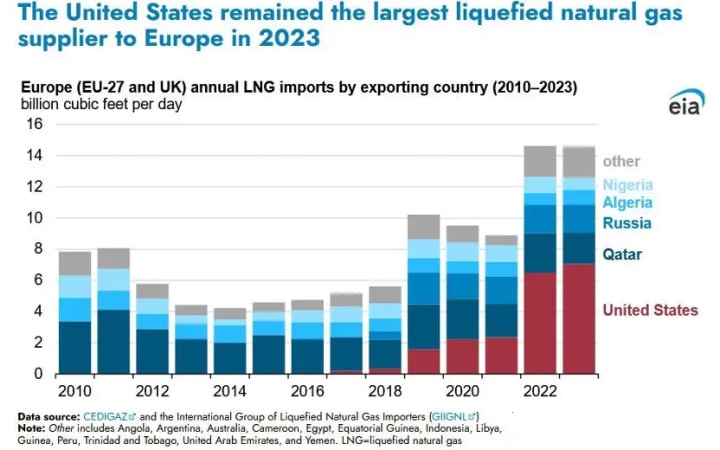

Norway is now Europe’s largest natural gas supplier, but the U.S. has significantly increased its role as well. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports from the U.S. have surged, benefiting from higher prices and rising European demand.

For Ukraine, losing $800 million annually in transit fees might seem concerning, but U.S. financial and military support far outweighs this loss. Western Europe, particularly France and Italy, is relatively unaffected due to their access to LNG via seaports—though at a higher cost. Poland has gone a step further, not only refusing to use Russian gas but also shutting down transit pipelines to ensure others can’t use them either.

For the U.S., the situation is a boon. American energy companies are enjoying massive profits, with energy stocks up 40-60% this year.

Russia’s Gas Still Flows, but Barely

Russia’s remaining gas supply to Europe is routed through a single pipeline that passes through Greece, Hungary, and Serbia. With global LNG production at approximately 500 billion cubic meters annually, the 14 billion cubic meters Russia supplies to Europe may seem negligible on a global scale. However, for countries without access to LNG terminals or seaports, this supply is crucial.

The Hardest Hit: Slovakia

Slovakia finds itself in the most precarious position. As Eastern Europe’s largest car manufacturer, its economy heavily depends on stable and affordable energy supplies. The loss of transit fees and high reliance on Russian gas have created a dual threat to its core industries.

In response, Slovakia has reportedly threatened to cut off electricity supplies to Ukraine—a sign of the severe economic strain this situation has caused.

China’s Strategic Advantage

For China, this shift is highly advantageous. Increased Russian dependence on China strengthens their economic ties and bargaining position. Simultaneously, disruptions in Europe’s energy market weaken its industrial base, including its automotive sector—a core competitor to China’s own car manufacturing industry.

Russia’s Natural Gas Pipeline Network: From Dominance to Decline

Russia theoretically has seven major pipelines capable of supplying natural gas to Europe, but as of now, only one remains operational. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

1. Yamal-Europe Pipeline

• Route: From Russia’s Yamal Peninsula through Belarus and Poland to Germany.

• Status: Closed. Poland refused to pay for gas in rubles after Russia demanded such payments as a countermeasure to U.S. sanctions. Consequently, Poland shut down this pipeline.

2 & 3. Nord Stream Pipelines

• Route: The Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines run under the Baltic Sea directly to Germany.

• Status: Non-operational. Both pipelines have been completely disabled following well-documented disruptions.

4. Brotherhood Pipeline

• Route: Transverses Ukraine to supply natural gas to Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, and Hungary.

• Status: Closed. Ukraine has halted operations.

5. Soyuz (Union) Pipeline

• Route: Another pipeline across Ukraine, providing gas to Germany, France, Romania, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, and Turkey.

• Status: Closed. Also shut down by Ukraine.

6. Blue Stream Pipeline

• Route: Directly supplies Turkey.

• Status: Operational. However, it doesn’t contribute to European gas supplies.

7. Turk Stream Pipeline

• Route: Traverses the Black Sea to deliver gas to Turkey and southeastern Europe.

• Status: Operational. Now the only pipeline connecting Russia to Europe, with an annual capacity of 31.5 billion cubic meters.

The “Turk Stream” pipeline is now the only remaining route for Russia to supply natural gas to Europe, with a maximum capacity of 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually. Alongside this, Russia supplies 29 bcm to China via pipelines, bringing its total pipeline exports to approximately 60 bcm. Additional smaller pipelines deliver gas to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkey through the “Blue Stream” pipeline, but their volumes are negligible. Russia’s pipeline exports to China might increase to 38 bcm this year, nearing the current capacity limit, as new pipelines are still under construction and far from operational.

Russia’s annual natural gas production stands at 636.9 bcm, with domestic consumption accounting for 450 bcm. This leaves roughly 190 bcm available for export. Subtracting the 60 bcm sent via pipelines, about 130 bcm remains. Consequently, Russia’s natural gas exports have shifted predominantly to maritime routes, marking a retreat from the era of pipeline dominance. This transition highlights the changing dynamics of Russia’s energy export strategy amidst geopolitical and infrastructural constraints.

When it comes to LNG (liquefied natural gas) carriers, the dominance lies with China and South Korea, each holding about half of the global orders, with other countries playing negligible roles. In terms of profit distribution, China, South Korea, and France equally share the benefits. France’s involvement is due to the monopoly of GTT, a French company that controls the market for LNG carrier containment systems, claiming a significant portion of the profits. However, in 2024, China broke this monopoly by delivering its first LNG carrier equipped with a domestically developed containment system. Although the initial ship’s capacity was relatively small, it signaled a shift towards greater independence in China’s LNG carrier technology, with expectations for broader adoption in the future.

Ukraine’s decision to shut down gas pipelines to Europe has inadvertently benefited Turkey, China, France, and South Korea, while Ukraine itself has forfeited a lucrative stream of transit fees. This move, however, seems self-inflicted, reflecting its strategic priorities. For European countries dependent on natural gas, this has translated into skyrocketing prices, an unexpected burden. Estimates suggest that European consumers might face an annual increase of €40 billion to €50 billion in natural gas costs, along with an additional €60 billion to €70 billion in electricity costs, as many power plants rely on natural gas. Ultimately, European consumers have become the unwilling victims of these geopolitical shifts, shouldering the financial fallout of a conflict-driven energy crisis.

The Energy Trilemma and the Ongoing Crisis

In the energy sector, there exists an inherent "trilemma"—it is impossible to achieve all three goals of green energy, stability, and affordability simultaneously. This fundamental contradiction shapes global energy policies and market dynamics.

Primary vs. Secondary Energy

Primary energy refers to natural resources like oil, coal, and natural gas, while secondary energy is derived from processing primary energy into other usable forms, such as electricity, coke, steam, and petroleum products like gasoline and diesel.

From a global primary energy usage perspective:

Oil holds the largest share at over 31%.

Coal comes second with 27%.

Natural gas ranks third at 25%.

In Europe, fossil fuels remain the dominant source of energy, collectively accounting for more than 70% of primary energy consumption. Among Europe’s major energy consumers, Germany stands out with a dependency rate of around 90% on imported crude oil and natural gas, making it particularly vulnerable to supply disruptions caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Russia’s Declining Role in European Energy

Before the conflict erupted in 2022, Russia supplied 40% of the EU’s natural gas needs. However, by 2023, Russian gas exports to Europe had plunged to just 8% of their 2018–2019 peak. The decline in supply, particularly from Russia's Far East, has kept European gas prices on an upward trajectory.

The U.S. and LNG Exports

Since 2022, the U.S. has emerged as Europe’s largest supplier of liquefied natural gas (LNG), maintaining this position through 2023. However, American LNG is significantly more expensive than Russian pipeline gas, contributing to the sharp rise in European gas prices since 2022.

The situation further deteriorated due to a combination of extreme cold weather in the U.S. and Ukraine’s decision to halt the transit of Russian gas. Natural gas futures for February delivery on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) surged by more than 20% intraday to $4.20 per thousand cubic feet, marking the largest single-day increase in nearly three years.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), American natural gas production has hit a bottleneck. Since the second half of 2023, dry gas output has averaged about 103.7 billion cubic feet per day. With heating season demand rising, inventory levels have been rapidly depleting, further straining supply.

Germany, as Europe’s industrial powerhouse, faces immediate challenges from rising energy costs, threatening its manufacturing sector and broader economic stability. Europe’s inflationary pressures are a severe blow to central banks eager to lower interest rates.

Ukraine, having lost approximately $1 billion in annual transit fees due to the halt in Russian gas transit, has also suffered significant financial setbacks—although its plight garners little international concern in this context.

The U.S. remains one of the biggest beneficiaries of the ongoing crisis, solidifying its dominance in Europe’s LNG market. Meanwhile, China is poised to continue benefiting as a secondary supplier, filling gaps in the European market.

Ultimately, the primary losers in this equation are Europe and Ukraine. Europe faces soaring energy costs, inflation, and economic uncertainty, while Ukraine struggles with the financial fallout of its diminished transit role. The crisis underscores the stark inequalities and geopolitical maneuvering within the global energy landscape.

About the Creator

Brian Chao

A Brian who has a cool brain.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.