The Double Marginalization of Black Biracial People

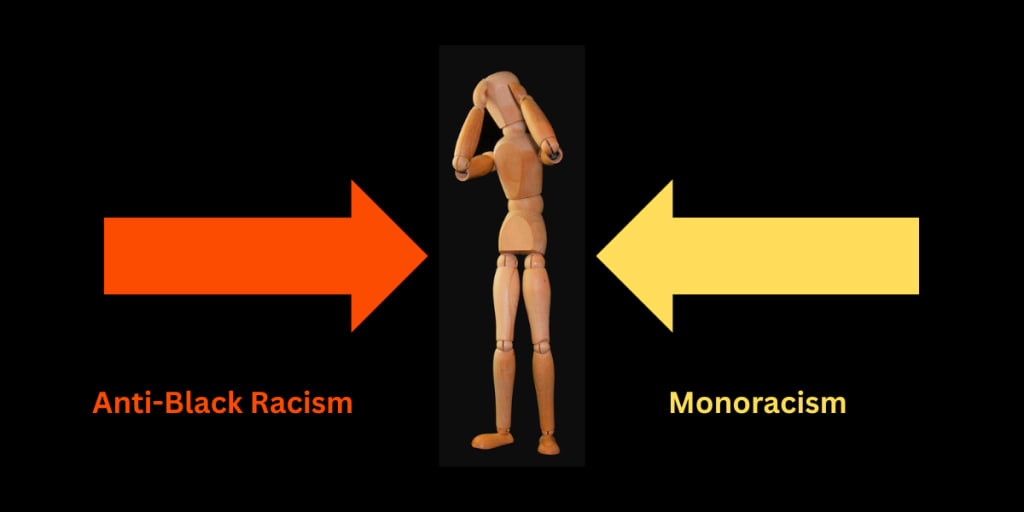

Black-White biracial individuals who are identified by society as monoracially Black bear the full weight of anti-Black racism while also experiencing monoracism that erases their mixed ethnic identity.

Author’s Note: This is an article written for a general audience and is distinct from the author’s academic work. The examples featured here happen to involve Black biracial women with White mothers.

For many, the word “biracial” evokes the image of an ethnically ambiguous celebrity who is widely perceived as white, if somewhat “exotic.” Think Meghan Markle.

But outside the world of the rich and famous, Black-White biraciality can look very different. A Pew Research Center report found that 61% of Black-White biracial individuals in the United States are perceived as Black.

Often unseen, then, are non-famous Black-White biracial individuals (people like me) whose mixed ethnicity is rendered invisible by a society fixated on maintaining rigid racial categories. I refer to this group as Black biracial individuals: people with one Black parent and one White parent who are socially categorized as monoracially Black.

Even after decades of research on multiracial identities, scholars often treat Black-White biracial individuals as a homogeneous group, frequently lumping “Black mixed-race” people together with non-Black mixed-race individuals in studies. Much of this work overlooks the fact that Black biracial people hold a unique positionality in society, existing at the intersection of Black and biracial identities. While non-Black biracial individuals experience monoracism (a form of oppression specific to mixed-race people), Black biracial individuals must deal with both anti-Black racism and monoracism.

Racism in White Spaces

When it comes to racism, it’s possible that Black biracial individuals face more frequent racialized encounters than monoracial Black people. Why would this be, you might ask? Well, having one white parent often translates to spending more time in predominantly white environments. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of experiencing prejudice when the biracial individual is socially read as Black. Black biracial American author Julie Lythcott-Haims shares a childhood memory from when she was about seven, living in Rockland County, New York. While swimming in a friend’s pool with several other children, she recalls:

… apparently one kid's father got wind of the fact that I was in the pool polluting it with my blackness, and he came to the door and said he wanted to bring his child home.

Growing up in 1980s Liverpool (UK), I went through experiences that were reminiscent of the racial hostility of the Jim Crow era. Once, my sister and I were chased by boys on bikes yelling racial slurs. Another time, a group of men stopped their car to order me to “smile” as I walked down the street. At school, anti-Blackness was usually more covert, though no less hostile: I was socially ostracized during my first year, and later, a classmate angrily lashed out when I objected to being patronized. I got through this period by keeping my emotions in check, staying hypervigilant, walking on eggshells, and focusing on my studies so I could eventually escape Liverpool. (As detailed in a personal narrative piece and mentioned in a previous op-ed).

The Monoracial Gaze

For Black biracial individuals, racism is compounded by monoracism, often manifesting as identity invalidation: misrecognition of family relationships; dismissal of multiethnic heritage; and pressure to identify with a single racial group. Being assigned to a group different from one’s mother and feeling obliged to conform to that group’s norms can be especially challenging during childhood, since the mother often serves as the primary attachment figure and, for girls, the principal role model. A 2024 study found that racial identity invalidation significantly contributes to depressive symptoms in Black-White biracial adolescents.

In her 2018 Master’s thesis examining how Black mixed-race women navigate dominant monoracial norms in the U.S., Corey Rae Evans describes how intense societal pressure pushed her to adopt a performative Black identity, modifying her speech and behavior to meet others’ expectations. She notes that failing to conform often resulted in judgment for straying from what was regarded as “Black behavior.” Evans also recalls her relationship with her white mother being misrecognized while visiting her mother’s hometown of Garrison, North Dakota:

…my sister and I experienced being racialized and “othered” by waitresses who disassociated us from our white mother when trying to provide us separate checks…

A similar account appears in the work of scholars Chandra Waring and Samit Bordoloi, who share the experience of a biracial interviewee describing how others perceive her when she is out in public with her white mother. The first scenario demonstrates the extent to which people attempt to impose a plausible explanation when encountering a family relationship that unsettles the monoracial gaze:

Typical experience will be if I am in a predominantly white town with my mother and people kind of give [us] a second look . . . like “Are they lesbians?” It’s very strange. Or they don’t think we’re together. We’ll be in line and she’ll start ordering something and they’ll ask me to the next counter and I’ll be like “I’m with her. Hello, I just called her Mom!”

During my undergraduate student years, I discovered that a fellow student had attended a secondary school in Liverpool, UK, where my mother taught English. I mentioned this, suggesting he might know her. Initially, the young white man was adamant that he didn’t and seemed almost irritated by the suggestion. However, a few minutes later, he returned, visibly embarrassed, and admitted, “I just realized your mother did teach me. I’m so sorry.” This encounter, which I first wrote about here, illustrates the role that societal racial categorization played in his initial inability to recognize me as her daughter.

Missing from the Conversation

While I cannot claim to speak for all Black biracial individuals, it is clear that many of us deal with intersecting forms of oppression. We experience the full weight of anti-Black racism: the hostility, the slurs, the constant scrutiny, as well as systemic bias. Growing up, we often face these challenges in predominantly white communities without the “safety in numbers” that more diverse spaces might offer. At the same time, we deal with monoracism: our close family relationships are misrecognized; we’re judged for speaking or acting in ways that do not correspond with society’s ideas of our identity. All of this creates ongoing pressure to disavow significant chunks of who we are.

Existing studies on multiracial individuals have tended to group all Black-White biracial people together, overlooking their unique circumstances. By paying closer attention to Black biracial people, researchers can explore new areas of study that address the neglected lived realities of this group. Additionally, focusing on the Black biracial experience can offer a deeper understanding of how racial categorization is imposed and experienced in modern Western societies.

© 2025 Clare Xanthos

About the Creator

Clare Xanthos

Researcher & Writer. Interests: racial equity, social justice, cultural identity. Co-editor & an author of 2 chapters in the book "Social Determinants of Health among African-American Men." PhD in Social Policy (London School of Economics).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.