Opinions or Ideological Harm

Nazi Villainy, Media Empathy, and U.S. Christian Nationalism

In contemporary American culture, few villains are as universally recognizable as the Nazi. From Hollywood blockbusters to political speeches, Nazis embody the archetype of hatred, cruelty, and authoritarianism. The swastika is shorthand for evil, and any resemblance to Nazi ideology is, in the public imagination, beyond the pale of civilized debate; despite it’s original context. Yet, beneath the clarity with which Americans condemn foreign fascism lies a paradox; ideologies at home that share disturbing similarities often receive softer treatment, particularly when cloaked in the language of religion and patriotism. When Americans see Nazis on screen, they are taught to hate them. But when American figures wrap racial and exclusionary rhetoric in the name of Jesus, they are too often treated as simply having “a difference of opinion.”

This distinction is not benign. A true difference of opinion exists when two parties disagree on matters of taste, method, or preference like whether one prefers one political policy over another or whether a particular social program is effective. Disagreement, in that sense, presumes a shared respect for the humanity and rights of others. But when rhetoric crosses into the territory of denying others’ fundamental dignity, safety, or equality; it is no longer an opinion. It becomes ideology. An ideology that not only undermines democratic values but also carries forward a historical lineage of exclusion and violence. When speech echoes the racialized imagery of the Ku Klux Klan, or when the figure of Jesus is weaponized to exclude those deemed “outsiders,” it ceases to be harmless expression and instead functions as an extension of historical white supremacy.

The roots of this problem are deeper than trees. Scholars like Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey, in The Color of Christ, demonstrate how Americans remade Jesus into a white, European figure and used that image to sanctify racial hierarchies. In this telling, the Son of God became less a universal savior than a cultural icon of whiteness. Stephen Prothero an American Religion Scholar, in American Jesus, similarly shows how depictions of Christ in the United States were never static; they were molded to fit the political and cultural needs of the nation. The KKK’s revival after D.W. Griffith’s film of 1915 Birth of a Nation is a key example. The organization openly identified as Christian, framing itself as the defender of white Protestant America against not only Black Americans and Jewish people but also Catholics whom they deemed “too European” and therefore insufficiently white. As historian Kelly Baker argues, their very appeal rested on presenting themselves as protectors of a Christian way of life, even as they wielded terror as a weapon.

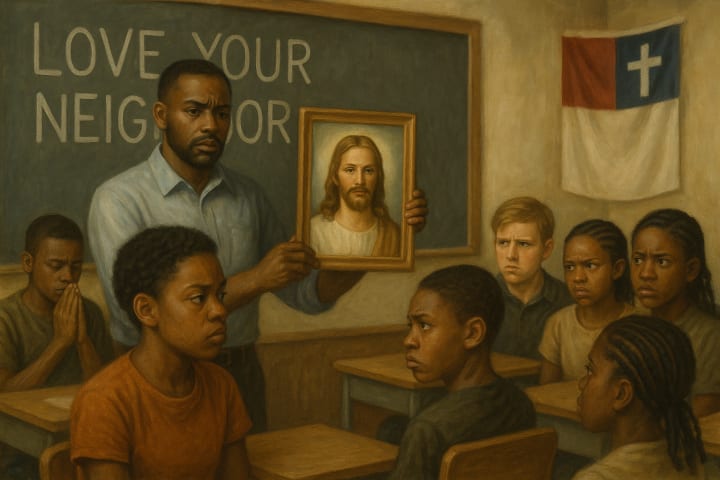

This blending of Christianity with white supremacy did not remain confined to the Klan. It shaped American popular theology and politics across the twentieth century. The racialized “White Jesus” appeared in Mormon art, Protestant churches, and children’s Bibles. This image comforted some but alienated many others, particularly Indigenous and Black communities, who were shocked to see the savior they worshipped presented as blonde-haired and blue-eyed. Even during the Holocaust, some Americans could dismiss Jewish refugees by insisting that Jesus was not Jewish at all, but rather a white figure unconnected to their plight. In such moments, theology and politics converged the manipulation of Christ’s image became a justification for exclusion, indifference, and cruelty.

Fast forward to 2025, and these dynamics continue to reverberate loudly. Media continues to portray Nazis as enemies to be hated, but homegrown ideologies that echo Nazi logic asserting the superiority of one group while dehumanizing others often escape equivalent condemnation. Figures like Charlie Kirk and other Christian nationalist voices publicly claim to worship Jesus, yet their rhetoric often mirrors the exclusionary patterns of the past; equating Christianity with whiteness, patriotism, and a narrowly defined “real America.” The contradiction is glaring. On the one hand, Americans are taught to despise fascism; on the other, fascist-adjacent speech is tolerated when couched in religious language.

Let’s argue that such speech must be recognized for what it is not a matter of “opinion” but an ideology of harm. Just as society understands Nazi propaganda as dangerous because it directly threatens the rights and safety of targeted groups, so too must we understand white supremacist Christian rhetoric as dangerous, not debatable. To allow it to pass under the banner of free speech or personal opinion is to ignore its history, its consequences, and its ongoing role in shaping American life.

By tracing the historical construction of white Jesus imagery, the Christian identity of the KKK, and the manipulation of religious symbols for political purposes, we can better understand how today’s rhetoric is not new but a continuation of long-standing traditions of exclusion. By comparing the cultural condemnation of Nazis with the tolerance of domestic hate speech, we can expose the contradictions in American discourse. And by reframing the boundaries of “opinion,” we can push toward a more honest recognition that speech which denies others’ humanity is not merely discourse; it is ideology and it is dangerous.

II. Historical Roots: Jesus, Race, and Whiteness

To understand why certain forms of Christian nationalist rhetoric in 2025 are so dangerous, we need to trace their historical roots. The portrayal of Jesus in America has never been neutral. From the colonial era through the twentieth century, depictions of Christ were repeatedly reshaped to support racial hierarchies, justify exclusion, and bolster political agendas. What emerges from this history is clear when Jesus was turned into a white figure, he became not just a religious symbol but a racialized weapon.

Protestant Iconoclasm and the Absence of Images

The earliest Protestant settlers in America brought with them a deep suspicion of images. Influenced by European iconoclasm, especially in places like Germany, Switzerland, and England, many saw depictions of Jesus and saints as idolatry. They drew on figures like John of Damascus, who defended icons in the eighth century, but inverted his arguments. For Protestants, to destroy images was to purify the faith. Churches in Europe had already been stripped bare of their paintings and statues; when Protestants came to America, they carried that same iconoclastic sensibility.

This meant that, in early colonial America, there were very few sanctioned images of Christ. Unlike Catholic communities in Spanish or French territories, where images of Mary and Jesus abounded, Protestant America deliberately avoided them. At first glance, this absence may seem to resist racialization. Without images, there was no need to debate what Jesus looked like. Yet this very vacuum created space for later generations to project their own racial and cultural assumptions onto Jesus.

The Emergence of White Jesus in Mormonism

By the nineteenth century, images of Jesus began to reappear in American religious life, most strikingly through the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Joseph Smith’s “First Vision” initially described a pillar of light. Later, Smith claimed to have seen Jesus himself; portrayed as white, with blue eyes and light hair. These descriptions circulated within Mormon communities, and eventually artists depicted Jesus according to this racialized vision.

This was not an isolated development. Rather, it was part of a broader cultural trend in which Americans sought to claim Jesus as their own, separating him from his Jewish heritage and Middle Eastern context. By making Jesus white, Americans reinforced the notion that their nation, their culture, and their faith were divinely favored. W. Paul Reeve has shown how Mormonism in particular wove together theology and race, using the image of a white Christ to set boundaries around who could fully belong within the community.

The KKK and Christian White Supremacy

If Mormonism helped popularize images of a white Jesus, the Ku Klux Klan crystallized their political use. Following the release of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915, the Klan experienced a massive revival. Its members openly identified as Christians, framing themselves as defenders of “Christian civilization.” Historian Kelly J. Baker notes that the Klan saw itself not just as a racial movement but as a religious one. Cross burnings were ritualistic acts meant to sanctify their cause.

The Klan’s enemies list reveals much about how it understood itself: African Americans, Jewish people, and Catholics were all cast as threats to white Protestant America. The targeting of Catholics is especially revealing. For the Klan, Catholicism represented a form of European-ness that did not align with their vision of whiteness. In other words, whiteness itself was not static; it was something to be defended, purified, and defined against outsiders, even European immigrants.

This obsession with purity extended into architecture and aesthetics. Just as fascist regimes in Europe embraced stark, stripped-down buildings to embody conformity, the Klan and its sympathizers rejected ornate Catholic traditions. They equated simplicity with purity, whiteness with godliness, and exclusion with holiness. Their Christianity was inseparable from their white supremacy.

White Jesus as a Political Tool

By the early twentieth century, white Jesus was firmly established in American popular culture. From stained glass windows to Sunday school illustrations, children grew up learning that the Son of God looked more like a Nordic figure than a Middle Eastern Jew. This transformation carried devastating consequences.

For enslaved Africans and their descendants, the discovery of white Jesus was jarring. As Blum and Harvey describe in The Color of Christ, many were shocked to learn that the figure they had prayed to for deliverance was presented by their oppressors as a white man. The irony was bitter. Enslaved people identified with the suffering Jesus of the Gospels but the Jesus shown to them in pictures bore the likeness of their enslavers.

The political use of white Jesus became especially evident during the Holocaust. As Jewish refugees fled Nazi persecution, some Americans justified their refusal to help by claiming that Jesus was not Jewish at all, but a white savior unrelated to the plight of his people. In this twisted logic, whiteness not only separated Jesus from his own heritage but also served as a reason to deny empathy to those in need. David Wyman’s research in The Abandonment of the Jews reveals the extent to which indifference, apathy, and even hostility shaped U.S. responses to Jewish refugees. White Jesus was not just a theological mistake; it was a tool of political exclusion.

Linking Past to Present

These historical developments matter profoundly for understanding the landscape of 2025. When contemporary Christian nationalists claim that America is a “Christian nation,” they are drawing upon this long tradition of fusing faith with whiteness; not the constitution or bill of rights faithfully. When they portray Jesus as the defender of American values against outsiders, they are recycling the very logic of the Klan, even if the names and symbols have changed.

The image of a white Jesus does more than depict a religious figure it encodes an entire worldview. It suggests that true faith is white, that true belonging is white, and that true authority comes from those who embody whiteness. Against this backdrop, claims that exclusionary rhetoric is merely a matter of “opinion” collapse. They are not opinions but manifestations of a racial-religious ideology that has been centuries in the making.

III. Media and the Nazi Archetype

If the construction of a white Jesus in America provided the theological roots of racialized exclusion, then media has supplied the emotional script by which Americans recognize and respond to hatred. For more than a century, film, television, and popular culture have trained Americans to view Nazis as the clearest expression of evil. The imagery is potent swastikas, goose-stepping soldiers, concentration camps, and the raised-arm salute all communicate fascism in shorthand. To see them is to recoil. But this moral clarity is double-edged. Because Americans have been conditioned to despise Nazis in such a visceral way, they sometimes fail to recognize similar ideologies when they emerge closer to home. If the Nazi archetype is the perfect villain then Christian nationalist or white supremacist rhetoric wrapped in religious language becomes harder to identify, critique, or condemn with the same urgency.

Birth of a Nation and the Birth of Villainy

It is no accident that one of the earliest and most influential films in American history, The Birth of a Nation (1915), tied together cinematic storytelling, racial politics, and Christian symbolism. While the film is infamous for its virulently racist depiction of African Americans and its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan, it also shaped how villains and heroes were imagined on screen. In Griffith’s story, Black men were the villains, threatening white purity and order, while the hooded Klan rode in as the saviors. Cross burnings, white-robed knights, and religious undertones elevated the Klan into almost divine defenders of civilization.

This film’s impact was immense. It not only revitalized the Klan but also offered Americans a framework for imagining racial conflict villains as racialized “others,” heroes as white Christians. In this way, Birth of a Nation created a dangerous paradox. It normalized white supremacist Christianity as heroic, while simultaneously laying the groundwork for later films to depict Nazis as evil. Hollywood’s language of villainy was already in place, but the characters occupying those roles could change.

The Nazi as Universal Villain

By the mid-twentieth century, Nazis had become the dominant symbol of evil in American media. During World War II, propaganda films such as Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series depicted the Nazi threat as a global menace that demanded American resistance. After the war, this framing only intensified. Films like Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) confronted audiences with the moral depravity of the Holocaust, while countless war movies reinforced the stereotype of Nazis as cruel, inhuman enemies.

In later decades, Nazis became convenient villains in popular culture precisely because they required no defense. From Indiana Jones battling swastika-bearing adversaries to Captain America punching Hitler on the cover of comic books, Nazis became a cultural shorthand for unquestionable evil. Even in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Hydra an organization explicitly tied to Nazi Germany embodied the archetype of authoritarian hatred.

The message was clear! Nazis were to be hated, resisted, and eradicated. Their ideology was not up for debate; it was inherently wrong.

The Problem of Externalizing Fascism

Yet this moral clarity came with a cost. By externalizing fascism as something foreign, something that belonged to Germany, to Europe, to the swastika; Americans could ignore or minimize fascist tendencies within their own borders. Domestic white supremacist violence was often framed as a fringe problem rather than an existential threat. When white supremacists bombed churches, lynched Black Americans, or marched with torches, their acts were often dismissed as “extremism” rather than recognized as part of the same ideological family as Nazism.

This disconnect persists in 2025. Americans may feel comfortable labeling a neo-Nazi march as dangerous, but when rhetoric is couched in biblical language; when preachers call LGBTQ+ people abominations or politicians frame immigrants as invaders in the name of Jesus; it becomes less obvious to many that these are also fascist expressions. The media has conditioned Americans to see the Nazi as the villain “over there,” but not necessarily the Christian nationalist as the villain “right here.”

Selective Empathy in Media Portrayals

Media portrayals also shape empathy. Films about Nazis often invite audiences to sympathize with Jewish victims, resistance fighters, or Allied soldiers. This cultivated empathy is powerful, but it is also selective. Viewers are encouraged to weep for Anne Frank, but they are not always encouraged to weep for the victims of white supremacist terrorism in Charleston, Pittsburgh, or Buffalo.

This selective empathy is not accidental. By confining villainy to Nazis, American media implicitly allows space for a softer reading of homegrown hate. Christian nationalist rhetoric may be portrayed as “controversial” or “divisive” rather than inherently evil. As a result, the targets of such rhetoric immigrants, LGBTQ+ communities, people of color must navigate a public discourse that treats their oppression as debatable rather than self-evidently wrong.

2025: Nazis vs. Christian Nationalists in the Media

In 2025, these dynamics remain entrenched. News outlets quickly condemn explicit Neo-Nazi groups but often handle Christian nationalist movements with caution, framing them as part of the culture wars. When a pastor calls for violence against marginalized groups, it may be reported as “provocative speech” rather than dangerous rhetoric. When politicians invoke Jesus to justify restricting voting rights or healthcare access, the framing is often about “policy differences” rather than ideological harm.

This double standard reflects the Nazi archetype at work. Because Nazis have been universally marked as villains, any resemblance to them is easy to condemn. But when the same exclusionary, rights-denying logic is wrapped in crosses, flags, and the name of Jesus, it becomes harder for the media and public to denounce with equal force.

The Need to Expand the Archetype

If American society is to confront the realities of 2025, it must expand its archetype of villainy. The Nazi is indeed an appropriate symbol of evil, but the moral clarity used to condemn Nazis must also be applied to domestic ideologies of exclusion. White supremacist Christianity, Christian nationalism, and other movements that weaponize faith to deny rights are not simply differences of opinion; they are ideological threats.

Media must be willing to name these threats plainly. Just as Nazi speech is recognized as inherently dangerous because of its historical consequences, so too should speech that denies the humanity of immigrants, queer people, or racial minorities be recognized as dangerous because of its lived consequences. To continue excusing such rhetoric as “debate” or “controversy” is to perpetuate selective empathy and allow harm to fester.

IV. Free Speech vs. Harmful Ideology

One of the most enduring myths in American political culture is that all speech is equal, that words are merely opinions to be debated in the marketplace of ideas. In this view, every voice; no matter how offensive or cruel has the same right to be heard, and disagreement is simply a matter of taste or perspective. But history, philosophy, and lived experience all reveal that this assumption is dangerously simplistic. Not all speech is equal. Some forms of speech function not as opinion but as ideological assault, seeking to strip others of their dignity, safety, or fundamental rights.

The Difference Between Opinion and Ideology

An opinion is subjective and personal. It reflects one’s taste, preference, or belief about how something should be done. Opinions might clash one person likes a particular policy, another does not; but the underlying humanity of both sides remains intact. An opinion about healthcare reform, tax policy, or even religious doctrine might spark debate, but it does not erase the legitimacy of the person on the other side.

By contrast, ideology operates at a deeper level. It is a worldview that seeks to organize society, distribute power, and define who belongs. When speech is grounded in ideology, it does more than express preference; it asserts who deserves protection and who does not. When someone says, “Immigrants are invaders,” or, “Queer people are abominations,” this is not an opinion about taste. It is a declaration of exclusion. It identifies whole categories of people as outside the bounds of humanity, unworthy of rights, and potentially deserving of harm.

This is why it is misleading to treat such statements as “opinions.” To do so confuses the disagreement of equals with the domination of one group over another. The former is the lifeblood of democracy; the latter is the seedbed of oppression.

Mill’s Liberty and Its Limits

Philosophers have long wrestled with this tension. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859) famously defended free speech as a cornerstone of liberal society. For Mill, the open exchange of ideas was essential for truth to emerge. Even false or offensive opinions, he argued, played a role in sharpening the truth through contestation.

But Mill also recognized a limit. His “harm principle” insisted that liberty does not extend to actions or by extension, speech that cause direct harm to others. In Mill’s own words, freedom of expression stops when it “harms others” by infringing upon their rights or safety. Modern defenders of unrestrained free speech often forget this nuance. They invoke Mill as though he endorsed unlimited tolerance, but in reality, he drew a boundary: speech that functions as harm, not dialogue, cannot claim the same protections as genuine opinion.

Hate Speech as Infringement, Not Debate

In the American context, this distinction becomes critical. When Christian nationalists preach that only certain groups belong in the nation, or when white supremacists use Jesus’ name to justify exclusion, their speech is not neutral. It directly infringes upon the rights of those targeted. For LGBTQ+ communities, being labeled an “abomination” is not merely offensive; it is a precursor to laws that deny healthcare, housing, or marriage rights. For immigrants, being described as “invaders” fuels policies of detention, deportation, and family separation. For racial minorities, being cast as perpetual outsiders legitimizes voter suppression, mass incarceration, and even violence.

This is not abstract. Words shape reality. Nazi propaganda did not remain words on a page; it laid the groundwork for genocide. Klan sermons did not remain “opinions” within churches; they fueled lynchings and terror. Today, rhetoric that casts entire groups as unworthy of rights similarly functions as a tool of oppression. To call such speech an “opinion” is to minimize its real-world impact.

The Free Speech Double Standard

Ironically, American society often recognizes this dynamic when it comes to Nazis but ignores it in other contexts. Nazi speech is seen as inherently dangerous. A swastika is not tolerated as “free expression” in polite society it is understood as a threat. Courts in the United States have wrestled with this, but culturally, the swastika is shorthand for hate.

Yet when preachers, politicians, or pundits say that America is a Christian nation where only “real” believers belong, their speech is often treated as a matter of free debate. The difference in framing is stark. Both Nazi and Christian nationalist rhetoric infringe on others’ rights, but only one is widely acknowledged as dangerous. This inconsistency reflects the archetype described earlier: Nazis are villains, Christian nationalists are participants in the “culture wars.”

2025: The High Stakes of Rhetoric

In 2025, the stakes of this distinction could not be higher. Far-right rhetoric has intensified in political rallies, churches, and online spaces. Laws restricting transgender healthcare, banning books, or limiting reproductive rights are justified with biblical language. When leaders insist that such policies reflect “Christian values,” they collapse the boundary between faith and state in ways that mirror the Klan’s fusion of whiteness and Christianity a century earlier.

This rhetoric is not harmless. It establishes conditions where violence becomes thinkable. Just as Nazi propaganda prepared the ground for mass violence, today’s exclusionary sermons and speeches prepare the ground for discrimination, hate crimes, and systemic inequality. To excuse such speech as “just another opinion” is to abdicate responsibility.

Beyond Selective Tolerance

The challenge then is to move beyond selective tolerance. A society committed to free expression cannot treat all speech as equal. The question must always be does this speech function as dialogue among equals, or as ideology that denies the equality of some? If it is the latter, then it is not opinion but harm.

This does not mean banning speech outright, though legal limits are one possibility. It means recognizing and naming harmful rhetoric for what it is. It means refusing to platform those who weaponize Jesus to justify hate. It means holding accountable the media, churches, and institutions that excuse exclusionary ideology as “debate.”

Naming Ideology as Harm

The distinction between opinion and ideology may seem abstract, but it has concrete consequences. Opinions can be disagreed with, debated, even tolerated. But ideologies of exclusion whether Nazi, Klan, or Christian nationalist cannot be treated the same way. They are not opinions in the marketplace of ideas; they are declarations of war on the humanity of others.

In 2025, when Christian nationalist rhetoric continues to rise, society must confront this truth. To do otherwise is to perpetuate the very harms we claim to oppose. Just as Nazi speech is recognized as dangerous because of its history, so too must American speech that denies rights in the name of Jesus be recognized as ideology of harm. Only then can we move beyond the illusion of “difference in opinion” and begin to protect the dignity and safety of all.

V. Empathy, Boundaries, and Selective Compassion

If one of the central ironies of American Christianity is the transformation of Jesus into a white nationalist icon, another lies in the manipulation of empathy. The very figure who preached love for one’s neighbor, care for the poor, and solidarity with the oppressed has often been recast as a weapon to justify exclusion. The consequences are profound, not only for those wielding such rhetoric but for those targeted by it. Marginalized communities, forced to endure dehumanizing speech and systemic inequality, have cultivated a form of empathy tempered by survival. They embody what might be called empathy with boundaries; a deep understanding of others’ suffering coupled with the recognition that unchecked compassion can leave one vulnerable to harm.

Jesus and the Disinherited

Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited (1949) offers a framework for understanding this paradox. Writing as a Black theologian during segregation, Thurman asked a simple but revolutionary question what does the religion of Jesus mean for those “with their backs against the wall”? For Thurman, Jesus was not the exalted white figure of American stained glass but a poor Jew living under Roman occupation, acquainted with suffering and marginalization. His message of love, then, was not abstract but rooted in solidarity with the oppressed.

For Black Americans, Indigenous peoples, immigrants, and others excluded by dominant society, this vision of Jesus offered hope. Yet it also demanded discernment. If Jesus stood with the disinherited, then empathy could not mean passivity. To love one’s enemy did not mean accepting abuse or permitting injustice. It meant recognizing the shared humanity of all while setting boundaries that protected the dignity of the oppressed.

Selective Empathy and Power

By contrast, those in positions of power have often displayed what might be called selective empathy. This is the empathy extended only to those who look, live, or believe like oneself. In American history, white Christians who embraced a white Jesus frequently reserved compassion for their in-group, while denying it to others. Enslaved Africans were excluded from Christian fellowship, Indigenous peoples were dismissed as savages, and Jewish refugees were abandoned to their fate.

This selective empathy is not only hypocrisy; it is structural. It allows those in power to maintain their dominance while claiming moral virtue. To feel for one’s own group while dehumanizing others is easier than confronting one’s complicity in oppression. Media portrayals reinforce this pattern, inviting audiences to weep for victims of Nazi brutality while ignoring victims of domestic racial violence. The archetype of the Nazi villain trains viewers in selective empathy: hate the foreign fascist, but tolerate the homegrown supremacist if he quotes scripture.

Empathy With Boundaries in Marginalized Communities

For those on the receiving end of hate speech and exclusion, empathy takes on a different shape. Communities targeted by white supremacist and Christian nationalist rhetoric cannot afford the luxury of boundless compassion. They must balance empathy with self-preservation.

This is where the concept of empathy with boundaries becomes crucial. LGBTQ+ individuals, for example, often extend understanding even to those who oppose them; recognizing that bigotry may stem from fear, ignorance, or indoctrination. Yet they also insist on boundaries: safe spaces, anti-discrimination laws, and cultural shifts that protect their existence. Similarly, immigrant communities often show resilience and generosity toward others, even while facing suspicion or hostility. Their empathy is expansive but not unlimited; it runs until it meets the line of survival.

This form of empathy is not weakness. It is wisdom born of necessity. To extend empathy without boundaries would be to enable harm. By insisting on both compassion and protection, marginalized groups embody a deeper form of love—one that honors both the humanity of the other and the sanctity of the self.

The Double Standard of “Christian Love”

This dynamic reveals the double standard at the heart of American Christianity in 2025. Figures who claim to embody “Christian love” often wield exclusionary rhetoric that strips others of dignity. They present their hatred as opinion, their bigotry as conviction, and their dominance as divine order. Yet when marginalized groups respond with empathy coupled with boundaries, they are accused of intolerance.

This inversion is striking. The very people who practice the closest approximation of Jesus’ radical empathy the disinherited, the excluded, the oppressed are cast as divisive. Meanwhile, those who weaponize Jesus to justify exclusion are portrayed as defenders of tradition. The irony is as old as the Gospels themselves, where Jesus was condemned by the powerful precisely because he sided with the vulnerable.

Media’s Role in Shaping Empathy

Media narratives reinforce these dynamics. Victims of foreign oppression are often granted full empathy on screen: the suffering of Holocaust victims, for instance, is depicted as unquestionably deserving of compassion. But victims of domestic oppression are often portrayed through a lens of suspicion. Black protestors are criminalized, immigrants are depicted as threats, queer people are framed as culture warriors. The empathy extended to Anne Frank is withheld from George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, or the children of Gaza or the children separated at America’s southern border.

This disparity shapes public perception. Audiences conditioned to extend empathy selectively find it harder to grasp why marginalized communities insist on boundaries. They confuse boundaries with hostility, failing to see them as protective. They demand compassion from the oppressed while excusing hatred from the powerful.

Toward a New Understanding of Empathy

To move beyond this cycle, American society must adopt a more honest understanding of empathy. True empathy is not limitless permissiveness. It is recognition of shared humanity coupled with a commitment to justice. It acknowledges suffering while refusing to enable abuse. In this sense, empathy with boundaries is not a contradiction but a fulfillment of empathy’s deepest purpose.

If Jesus is understood as standing with the disinherited, then the boundary-setting of marginalized groups is profoundly Christlike. It embodies love that does not erase difference but honors dignity. It refuses to dehumanize even the oppressor, but it also refuses to surrender to oppression. This vision of empathy challenges both the selective compassion of the powerful and the sentimentalism of those who would reduce empathy to niceness.

The Strength of Boundaries/Empathy

In 2025, as Christian nationalist rhetoric continues to spread, marginalized communities model a form of empathy that should be recognized and honored. Their compassion is real, but it is not naïve. It is tempered by history, sharpened by survival, and bounded by the demand for justice. In contrast, the selective empathy of those who wield a white Jesus to exclude is not empathy at all but tribalism disguised as morality.

The path forward requires rejecting the double standard. If Americans are taught to hate Nazis because of the suffering they inflicted, then they must also learn to reject domestic ideologies that inflict suffering in the name of Jesus. And if empathy is to mean anything in this landscape, it must be empathy with boundaries; compassion that does not capitulate, love that does not excuse harm, and solidarity that does not erase the need for self-protection.

VI. Dangerous Rhetoric in 2025

The year 2025 is not unfolding in a vacuum. The rhetoric circulating in American churches, political rallies, and media outlets is part of a long genealogy of weaponized Christianity and racialized exclusion. The difference now is that the stakes feel more immediate, the platforms more pervasive, and the consequences harder to ignore. When Americans encounter overt Nazi imagery, they instinctively recognize the danger. Yet when rhetoric that mirrors the Nazi worldview emerges in Christian nationalist sermons or political speeches, it is too often tolerated as legitimate debate. This tolerance is not neutrality; it is complicity.

From the Pulpit to the Podium

In 2025, Christian nationalism has moved from the fringes to the mainstream. High-profile figures of preachers, podcasters, and politicians speak openly of America as a “Christian nation” where “real Americans” are those who conform to white, conservative, Protestant norms. When pastors declare that LGBTQ+ people are “abominations,” or that immigrants are “invaders sent to destroy our culture,” they echo the exclusionary logic that fueled both the Klan and Nazi Germany.

This rhetoric is not confined to isolated churches. It flows into political rallies where candidates vow to defend “Christian values” by curbing reproductive rights, restricting gender-affirming healthcare, or limiting what can be taught in schools. It echoes in courtrooms where laws are passed under the guise of protecting “religious freedom,” while in practice they narrow rights for women, queer people, and racial minorities. The pulpits and podiums of 2025 reinforce each other, creating a feedback loop in which ideology masquerades as opinion and harm masquerades as freedom.

The Role of Social Media

The danger of this rhetoric is amplified by digital platforms. Social media allows exclusionary messages to spread with unprecedented speed, reaching audiences far beyond the church pews. Clips of sermons calling for the subjugation of women or the criminalization of queer people circulate widely, gaining traction among audiences primed by grievance politics. Algorithms reward outrage, pushing the most incendiary content to the top.

This creates what scholars call “networked hate,” where ideological communities form online and reinforce one another. Unlike the pamphlets and rallies of the past, today’s digital networks allow hateful rhetoric to globalize, cross-pollinating with far-right movements in Europe and beyond. In this way, American Christian nationalism becomes not only a domestic threat but part of an international resurgence of authoritarian populism.

The “Opinion” Shield

Despite the harm such rhetoric causes, it continues to hide behind the shield of “opinion.” Media outlets often frame exclusionary speech as part of the “culture wars,” presenting both sides as though they are equally legitimate. When one side argues for the dignity of marginalized people and the other argues for their erasure, this false equivalence is more than journalistic laziness; it is moral failure.

The appeal to free speech is often deployed here. Defenders of dangerous rhetoric claim that they are simply expressing their beliefs, that their sermons or policies are no more than religious conviction. Yet, as argued in the previous section, the line between belief and harm is not so easily blurred. When words directly inspire policies that strip away rights, they cease to be neutral opinions. They become ideological weapons.

The Cost of Dangerous Speech

The costs of this rhetoric are visible in lived experience. Transgender youth face rising rates of depression and suicide as state after state passes laws restricting their access to healthcare. Immigrants live under the threat of deportation, their families torn apart by policies justified in biblical terms. Black communities confront police violence and voter suppression fueled by narratives of “law and order” steeped in racial bias. Jewish and Muslim Americans endure rising hate crimes, often incited by conspiracies that frame them as enemies of “Christian America.”

Each of these realities demonstrates the same pattern: speech that frames entire groups as threats creates conditions for systemic harm. The people targeted by such rhetoric cannot afford to dismiss it as “just words.” They live with the consequences daily, their dignity eroded by the normalization of exclusion.

Lessons from History

The danger of dismissing harmful rhetoric as harmless is not new. Nazi Germany offers the clearest example. Long before the camps, there were words. Speeches, pamphlets, and propaganda declared Jews to be vermin, degenerates, enemies of the Volk. These words did not remain abstract; they prepared the ground for violence. Similarly, the Klan’s sermons did not stay in pulpits; they legitimized lynchings, segregation, and terror.

In 2025, the parallels are hard to miss. To say that queer people “should be eradicated,” or that immigrants are “invading our nation,” is to echo the language of historical oppressors. To excuse such speech as “debate” is to ignore the lessons of history. If we condemn Nazi rhetoric for its role in preparing genocide, then we must also condemn American rhetoric that prepares exclusion and violence.

The Role of Empathy With Boundaries

Here, the concept of empathy with boundaries reemerges as a moral compass. Marginalized communities continue to extend empathy even toward those who hate them, recognizing the humanity of their oppressors. Yet they also set boundaries, insisting that compassion does not mean tolerance of abuse. Their response highlights what broader society must learn: to reject the false neutrality of dangerous rhetoric without surrendering to hatred in return.

Boundaried empathy offers a model for resistance. It allows for recognition of human frailty; the fear and ignorance that often drive exclusionary rhetoric while refusing to allow such frailty to justify harm. In this way, marginalized communities embody the resilience and clarity needed to confront the dangers of 2025.

Toward a Culture of Accountability

The task before America in 2025 is to move beyond tolerance of dangerous speech toward a culture of accountability. This does not mean suppressing all dissent or policing every word. It means naming harmful rhetoric for what it is and refusing to excuse it as opinion. It means demanding that media stop offering false equivalence, that politicians stop hiding behind religious freedom, and that churches confront the weaponization of their faith.

Accountability also means amplifying alternative voices. Theologies of liberation, grassroots movements, and interfaith coalitions all offer narratives of inclusion that counteract exclusionary rhetoric. By centering these voices, society can reclaim the moral clarity that has too often been reserved only for condemning Nazis.

Naming the Danger

In 2025, the most dangerous rhetoric is not always accompanied by swastikas or goose steps. It often arrives in church sanctuaries, on political stages, or in viral videos wrapped in crosses and flags. Its danger lies not in its novelty but in its familiarity, echoing centuries of weaponized Christianity and racial exclusion.

The challenge is clear. If Americans have been trained to despise Nazis because of the harm they caused, then they must also learn to despise the domestic ideologies that mirror Nazi logic under the name of Jesus. Dangerous rhetoric cannot be excused as mere opinion. It is ideology, it is harm, and it is a threat to democracy and human dignity alike. To fail to recognize this is to repeat the very mistakes history has already warned against.

VII. Conclusion & Call to Action

The story of America’s Jesus is, in many ways, the story of America itself. From the earliest days of colonization through the twentieth century and into 2025, the image of Christ has been molded, contested, and weaponized. Scholars like Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey have shown how a white, European-looking Jesus was not a neutral figure but a tool of cultural power; a way of sanctifying whiteness, nationalism, and exclusion. That weaponization of faith provided legitimacy for the Ku Klux Klan, for segregationists, and for countless preachers and politicians who claimed that God Himself endorsed their supremacy.

At the same time, media shaped how Americans understood evil. The Nazi became the archetypal villain, the shorthand for hate. Films, books, and cultural narratives conditioned Americans to despise Nazis with moral clarity, to see their rhetoric as dangerous and their ideology as intolerable. Yet this clarity often stopped at the nation’s borders. When Christian nationalist rhetoric inside the United States mirrored the exclusionary logic of Nazism, it was tolerated, excused, or reframed as “opinion.” The contradiction is glaring: hate speech abroad is condemned as fascism; hate speech at home is defended as free expression.

This essay has argued that such rhetoric must no longer be treated as mere difference of opinion. A true opinion is a matter of preference, taste, or perspective. But when speech declares whole groups of people unworthy of dignity or rights, it is no longer opinion—it is ideology. And ideology, when it dehumanizes others, is inherently harmful. Whether it takes the form of Nazi propaganda, Klan sermons, or twenty-first-century Christian nationalist talking points, the pattern is the same: words that deny humanity pave the way for acts that destroy humanity.

The Stakes of 2025

In 2025, the danger is not abstract. Across the country, laws are being passed that curtail the rights of women, queer people, immigrants, and racial minorities; often justified in biblical language. Social media amplifies messages of exclusion, creating global networks of hate. Political figures court Christian nationalist movements, legitimizing their rhetoric at the highest levels of government. These are not isolated incidents; they are part of a continuum that stretches back through American history to the fusion of whiteness, Christianity, and nationalism.

The stakes are not only political but existential. For marginalized communities, dangerous rhetoric translates into daily vulnerability: denied healthcare, restricted freedoms, targeted violence. For democracy itself, such rhetoric erodes the principle of equal dignity, creating a hierarchy of belonging that undermines the very idea of pluralism. To tolerate such speech as “debate” is to abdicate responsibility for the lives and futures it threatens.

Empathy With Boundaries as Resistance

Yet the response from marginalized communities demonstrates a path forward. By practicing empathy with boundaries, they model a form of love that is both radical and realistic. Their empathy extends even to those who oppress them, recognizing the humanity in every person. But their boundaries refuse to enable harm. They insist on laws, spaces, and protections that safeguard dignity. This combination of compassion and resilience is not weakness but strength. It embodies the very spirit of Jesus as envisioned by Howard Thurman: solidarity with the disinherited, love that resists domination, hope that refuses despair.

If America is to move forward, it must learn from this model. Boundaried empathy offers a way to resist hate without becoming consumed by it, to stand firm against exclusion while refusing to replicate its cruelty. It challenges the selective empathy of those who reserve compassion only for their in-group and invites a broader, deeper solidarity.

Media’s Responsibility

Media also has a critical role to play. Just as film and television trained Americans to despise Nazis, so too can they help expand the archetype of villainy to include domestic ideologies of exclusion. The swastika must not be the only shorthand for hate; the cross wielded as a weapon must also be recognized as dangerous. News outlets must abandon the false equivalence that presents exclusionary rhetoric as merely “controversial.” Entertainment media must depict the harms of Christian nationalism as clearly as it depicts the harms of fascism abroad. Stories shape empathy, and empathy shapes action.

A Call to Institutions

The call to action does not end with media. Churches must confront the ways their faith has been weaponized. Politicians must reject the temptation to exploit Christian nationalism for short-term gain. Schools must teach the full history of how religion, race, and power have intertwined in America. And citizens must hold each other accountable, refusing to excuse hate speech as opinion and instead naming it for what it is: ideology of harm.

This is not an easy task. It requires courage to confront the traditions and institutions that many hold dear. It demands humility to admit complicity. And it asks for vision; to imagine a society where Jesus is not the property of whiteness, nationalism, or exclusion, but a figure of radical love and solidarity.

Choosing Clarity Over Comfort

The greatest danger is not only in the rhetoric itself but in the comfort of denial. It is easier to believe that Nazis were evil “over there” and that American Christianity is inherently good “over here.” It is easier to frame bigotry as an opinion than to confront it as ideology. It is easier to allow selective empathy than to demand boundaried compassion. But comfort comes at a cost. To choose comfort over clarity is to leave the disinherited vulnerable, to allow harm to fester, and to repeat the mistakes history has already warned against.

The choice before America in 2025 is stark. Will it continue to excuse dangerous rhetoric as opinion, tolerating ideologies that deny humanity in the name of Jesus? Or will it recognize the danger for what it is and act with the same clarity it has long reserved for Nazis?

Final Words: Toward a Different Future

To honor the lessons of history, America must confront its contradictions. It must admit that Christian nationalism is not simply another viewpoint but a threat to democracy, dignity, and life itself. It must reject the false neutrality of media that frames exclusion as debate. It must amplify the voices of those who practice empathy with boundaries, whose love is strong enough to resist harm without surrendering to hate.

The call to action is simple, though not easy

- Name dangerous rhetoric as ideology, not opinion.

- Refuse to platform hate disguised as faith.

- Expand the archetype of villainy beyond Nazis to include domestic supremacists.

- Honor empathy with boundaries as a model for resistance.

- Choose clarity over comfort, justice over neutrality, solidarity over selective empathy.

In doing so, America can begin to dismantle the weaponization of Jesus and reclaim him as a figure of love, justice, and hope for all. In failing to do so, it risks repeating the same patterns that allowed hate to flourish in the past. The choice remains urgent. The time to choose is now.

Citations

Baker, K. J. (2017). Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915–1930. University Press of Kansas.

Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S. L. (2020). Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. Oxford University Press.

Blum, E. J., & Harvey, P. (2012). The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America. University of North Carolina Press.

Thurman, H. (1996). Jesus and the Disinherited. Beacon Press. (Original work published 1949)

Wade, W. C. (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press.

Prothero, S. (2003). American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Reeve, W. P. (2015). Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and the Problem of Racial Innocence. Oxford University Press.

Kelley, S. (2002). Racializing Jesus: Race, Ideology and the Formation of Modern Biblical Scholarship. Routledge.

Wyman, D. S. (1984). The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941–1945. Pantheon Books.

John of Damascus. (1980). On the Divine Images: Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images (D. Anderson, Trans.). St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. (Original work published ca. 730 CE)

Smith, J. (2013). The Joseph Smith Papers: Histories, Vol. 1: 1832–1844. Church Historian’s Press. (Original writings from 19th century)

Grem, D. E. (2012). Review: The Color of Christ. Journal of Southern Religion, 14. Retrieved from http://jsr.fsu.edu/issues/vol14/grem.html

Williams, R. L. (2012). Review: The Color of Christ. Journal of Southern Religion, 14. Retrieved from http://jsr.fsu.edu/issues/vol14/williams-r.html

Thurman, H. (1976/1996). Jesus and the Disinherited (Beacon Press). Chapter 2: Fear. Study guide PDF. Epiphany Episcopal Church. Retrieved from https://epiphany-md.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Jesus-and-the-Disinherited-Chapter-2.pdf

Thurman, H. (1949). Jesus and the Disinherited. Internet Archive (Digital Library of India). Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.260684

Cook, S. E. (2019). Book Review: Jesus and the Disinherited by Howard Thurman. OKH Journal: Anthropological Ethnography and Analysis Through the Eyes of Christian Faith, 3(2). Retrieved from ResearchGate.

Smidt, C. E. (2024). Christian nationalism, civic republicanism, and radical individualism: Conceptualizations, measurement, and differentiation. Religions, 15(11), 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15111364

Everton, S. F. (2024). Not all Christian nationalists are White (and not all White nationalists are Christian). Frontiers in Social Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1465810/full

Bullock, J. G., & Kalkan, K. O. (2023). Modeling nationalism, religiosity, and threat perception. PLOS ONE, 18(2), e0281002. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0281002

Corcoran, K. E., Scheitle, C. P., & DiGregorio, B. D. (2021). Christian nationalism and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0256939. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8489517/

Whitehead, A. L., Perry, S. L., & Baker, J. O. (2020). Christian nationalism and anti-vaccine attitudes. Socius, 6, 1–12. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023120977727

Davis, N. T. (2023). The psychometric properties of the Christian Nationalism Scale. Politics & Religion, 16(3), 494–509. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion/article/psychometric-properties-of-the-christian-nationalism-scale/61E45CF1C4FDF42BF1608F2C86FA7CF1

Perry, S. L. (2025). The religion of White identity politics: Christian nationalism and White racial solidarity. Social Forces. (Open Access ahead-of-print). https://academic.oup.com/sf/advance-article/doi/10.1093/sf/soaf031/8030582

Leu, J. (2021). God in our image: Race reflected in the Black Christ of Daule. Say Something Theological, 5(1). https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=saysomethingtheological

Tshaka, R. S. (2021). If the colour of Jesus is not an issue, why are you so insensitive about the rejection of the White Jesus? Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, 47(3), 1–14. https://unisapressjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE/article/download/6594/4361/39600

LaPlaca, J. (2013). Religious images through Protestant eyes. Henry J. Rooks, Jr. and Charles S. Beets Conference Papers. https://digitalcommons.calvin.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=religion_beets (useful background on Protestant iconoclasm)

VanDrunen, D. (2019). Pictures of Christ: Iconoclasm, incarnation, and eschatology. The Calvinist International / CPJ. https://www.cpjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CPJ5-VanDrunen-PicturesofChrist-1.pdf

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Propaganda and the American public. https://perspectives.ushmm.org/collection/propaganda-and-the-american-public

Lippert, J. (2021). The Associated Press and Nazi Germany, 1933–1938. Celebration of Student Scholarship. https://commons.nmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=celebration_student_scholarship

About the Creator

Cadma

A sweetie pie with fire in her eyes

Instagram @CurlyCadma

TikTok @Cadmania

Www.YouTube.com/bittenappletv

Comments (1)

One of the problems is that when people see themselves as the “good guys “ the “hero” and the other side the bad guys and the villain they block themselves from seeing many things.