Empty Chairs, Full Power: A Texas Dream

(with a note of irony)

Once upon a Monday in Texas, the Governor had a dream.

In it, he stood tall. Figuratively. He sat in his wheelchair, as he always does, but spoke like a man six feet above the floor and ten feet above criticism.

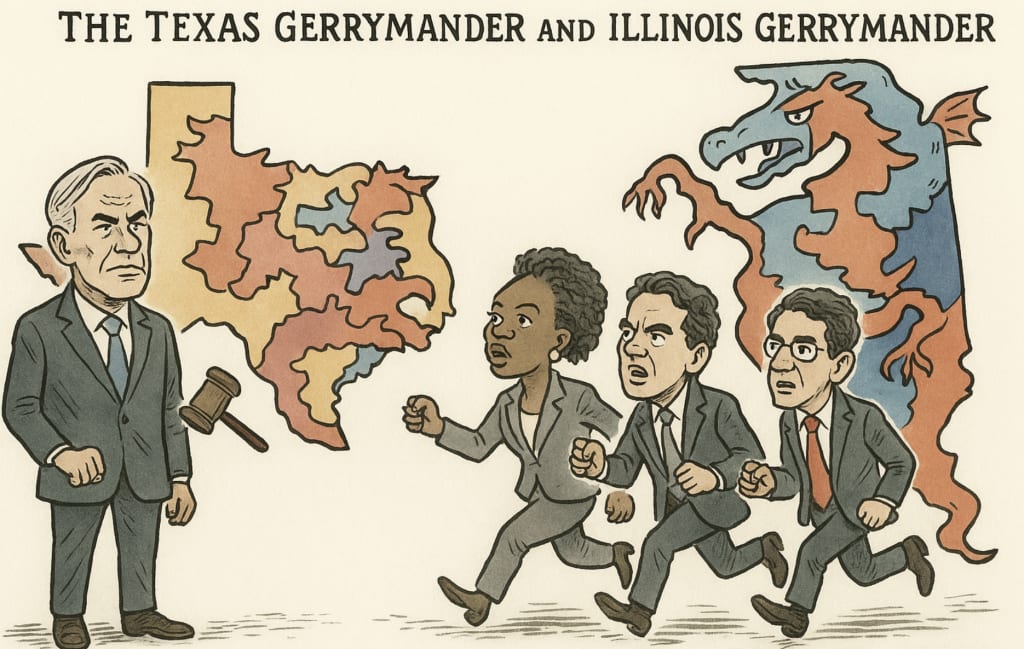

More than fifty Democratic lawmakers had fled the state, heading to Illinois, New York, and Massachusetts (which no one outside Boston has ever pronounced correctly). Their goal was to block a mid-decade Texas redistricting plan they believed would dilute minority voting power and rig the game in favor of new Republican seats.

The Governor declared they had "forfeited" their seats. He threatened $500-a-day fines, extradition, and legal charges if they did not return. It was a spectacle of ire and authority, and one that came with press conferences, legal footnotes, and plenty of gesturing.

This wasn’t the first time chairs in the Texas Capitol had gone empty. Back in 2003, Democratic lawmakers pulled the same maneuver, fleeing to Oklahoma in an effort to stop a Republican-led redistricting map pushed by then-Congressman Tom DeLay. That one worked just long enough to cause headlines. Then in 2021, during a heated battle over voting laws, Democrats again fled the state, this time to Washington, D.C. (that’s District of Confusion, depending who you ask). They returned to find the laws passed without them. The chairs always refill. The maps always get drawn.

Meanwhile, in Illinois, the latest generation of fleeing lawmakers gathered, sipping coffee and nodding thoughtfully at one another. They met with local Democrats. They held town halls. They took selfies. Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker (pronounced “Pritz-ker,” though most Texans still say it like a cough) rolled out the welcome mat. It was framed as a political alliance, but some called it a sanctuary of selective memory.

Because Illinois, as it turns out, is not exactly a bastion of redistricting virtue. It is one of the most notoriously gerrymandered states in the union. Its congressional lines resemble spilled spaghetti more than representative geometry. Democrats there have long drawn districts that snake through neighborhoods like political plumbing—twisting to pack or fracture voters with surgical precision.

So, while Texas Democrats walked out in protest of gerrymandering, they found shelter in a state that has long treated map-drawing like a contact sport. Illinois had districts that could only be drawn by cartographers on a bender, and yet no one seemed to mind, so long as the lines led to blue seats.

Back in Texas, the lawmakers called the new map a threat to minority voters, a violation of civil rights, and a return to the dark days of voter suppression. But quietly, some observers noticed that several of the new districts were majority-Hispanic, just in places where Hispanic voters had started leaning red. The outrage came not because minorities were being erased, but because they might elect the wrong people.

And so, representation was no longer about who the district belonged to, but who the voters belonged to. Both parties claimed the moral high ground. Both parties drew lines to stay in power. And neither side liked the result, unless it tilted in their favor.

Pritzker defended Illinois’ maps as lawful. Of course he did. Governors rarely object to maps that bless their party’s future. Still, even some of his allies admitted the contrast was hard to ignore. Though not too loudly. You wouldn’t want to disturb the illusion.

Mr. Hot Wheels, as one Democratic representative called the Governor of Texas, kept the show going. He gave interviews. He issued warnings. He spoke of duty and democracy, which, in his dialect, meant “my seat first, your vote second.” He threatened legal consequences. Still, the lawmakers stayed gone. And the Capitol sat half empty.

And the dream? Still just a dream, with a dash of paradox baked in.

The people, those who watched from homes, barbershops, diners, and back porches, were left wondering what any of it meant for them. Their electricity bills were still high. Their roads were still broken. Their neighborhoods still flooded when it rained too hard. The only maps they cared about were the ones that led to decent schools or open hospitals.

But no one drew those lines anymore.

Because in the rotunda of power, redistricting wasn’t about representation. It was about survival. It was less about voters than it was about victory. And the louder both sides shouted about principle, the more the people heard the sound of chairs scraping against marble—and not much else.

So, what is the Moral?

When folks set out to flee a crooked map and end up sitting in one just as bent, the story don’t unfold like protest—it folds in on itself.

And when both the ones drawing lines and the ones running from them claim to be saving democracy, you’d best bring a compass, because sooner or later, everyone starts walking in circles.

About the Creator

Mike Barvosa

Texas-based educator. Always listening.

I write about what we ignore, where memory fades, systems fail, and silence shouts louder than truth. My stories don’t comfort. They confront.

Read them if you're ready to stop looking away.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.