'What kind of idiots are we?'

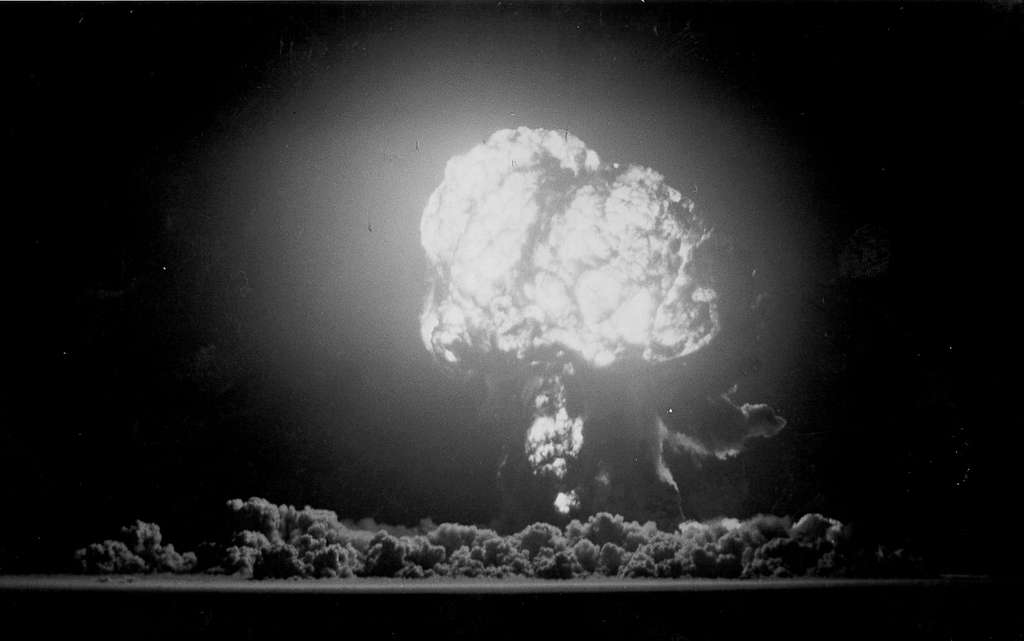

Nuclear war - reflecting on our mortality

Warning: some readers might find this content very challenging. If this is you, please close this article now.

I've applied some slight journalistic license for effect from the quote I used in the title, but the message is the same.

This is the top comment, by likes, written in response to a recent article in the UK national press about the likelihood of nuclear war:

Here we are, in the 21st century, and after two world wars and countless relatively minor ones which killed hundreds of millions of human beings, we see a third world war as becoming more and more likely. We just won't learn. WW3 would cause tens, possibly hundreds of millions to be vapourised in an instant, hundreds of millions burned to death, and hundreds of millions severely injured without any hope of medical aid. All this on Day 1. To follow would be hundreds of of millions, possibly billions, dying of radiation poisoning, starvation, cold and disease. We would also take with us billions of other species. What manner of idiots are we to even think about causing such an event?

The top reply to this comment stated, simply:

Every human being on this planet should read your post

Why, in the full knowledge of our likely complete destruction, do we carry on beating the war drums? Can there be any justification for imagining a world in which there is no imperative to work for our own destruction - and then build towards it?

In preparing to write this article, I found on YouTube a trilogy of three episodes of ten minutes each recorded from the original "Threads", a BBC docudrama screened decades ago when the cold war between the Soviet Union and United States was still very much a fact of life, and the peril of nuclear Armageddon hung over people's heads. Having lived through that period, I can certainly vouch for the veracity of this feeling at the time.

The screening brought into vivid reality an imagined story-line in which a salvo of three sets of nuclear explosions hit the UK industrial city of Sheffield and its surroundings, in the context of an escalating third world war between the nuclear powers resulting in an all-out global nuclear exchange.

Drawing on the best of scientific research and knowledge, the film focused on the lives of a handful of people and their immediate families or co-workers. Without sparing the feelings of the viewer more than absolutely necessary, the impacts of the build-up; the explosions themselves; and the immediate and following aftermath on the survivors is played out.

The film makes plain the impact of nuclear war. Buildings blown apart; administration thrown into inept chaos; innocent people either burned to a crisp or else simply vapourised. The fate of many survivors is little better: many needing immediate or urgent medical attention are left to die; with no electricity or water doctors and the health system are rendered impotent; age-old diseases kept at bay through modern sanitation and health care become common once more.

This is not even the worst of it though. The drama's title, 'Threads', reminds the viewer that our modern civilisation depends on a very fragile network of dependencies in order to keep running. Once broken - severed - this civilisation is simply torn apart. All the threads of the network - the web - on which it depends are cut.

Probably one of the most harrowing scenes in the film was the moment in which one of the survivors realises that there is no help coming: no-one and nothing between the ravages of radiation sickness and its inevitable outcome: death.

Many Britons watched this film as a child, including me. The impact "Threads" had on them is still felt, after decades. One viewer saw it at the age of 13, and couldn't sleep for weeks afterwards. Many felt that it was shocking, grim, bleak, depressing; worse by far than any Hollywood portrayal. Soul-destroying and haunting. Two comments on YouTube particularly stand out: "This needs to be shown to everyone in power or a position to authorise nuclear strikes". "It makes me feel really sad that we are facing the same dangers now than we faced back 1984 when this was first shown."

Definite echoes from the quote at the top of this article.

I felt on watching this portrayal of nuclear war that the fate of everyone whose story was told in the film - and all those whose life-stories were implied not told - was somehow more than mere death of the individual. This is death of the entire civilisation: all of the cultural understandings and artifacts that we hold dear and take for granted; all of society's networks and dependencies; and all of the learned and carried down knowledge on which civilisation itself has been built.

This to me is the 'greater death': it is 'more death' than merely our own death.

However terrible for any survivors, this is not all to consider. As the stories of those who survived the 1945 nuclear bombs in Japan show, the impacts on them of even this comparatively limited unimaginable hell weren't limited to health effects. The victims, called 'bomb affected people' or 'hibakusha' - people who had witnessed victims for whom "most of their clothes had completely burned away and their flesh was melting" - were shunned, discriminated against; not allowed to marry into other families. The 'death' they had experienced was too much for some who feared too close an association, lest they be affected too.

Of course, we've seen this plenty of times since. The AIDS epidemic, for one.

If you've managed to follow me all the way to this point, well done. Contemplating these almost unimaginable horrors that nuclear war can inflict on hundreds of millions, billions, of innocent people is utterly gut-wrenching. No-one with any shred of conscience can possibly stand to one side and let the build up to nuclear war happening without feeling torn apart inside.

But the thing is, there is such a glaring contradiction here: so obvious that it actually defies logic. On the one hand, there is hardly a person that would disagree that nuclear war is too terrible to contemplate. On the other, nearly all of us perpetuate behaviours that inescapably lead humanity towards all out war. We seem, at best, to be circling the drain; barely able to hold ourselves out of the clutches of the spectre of annihilation.

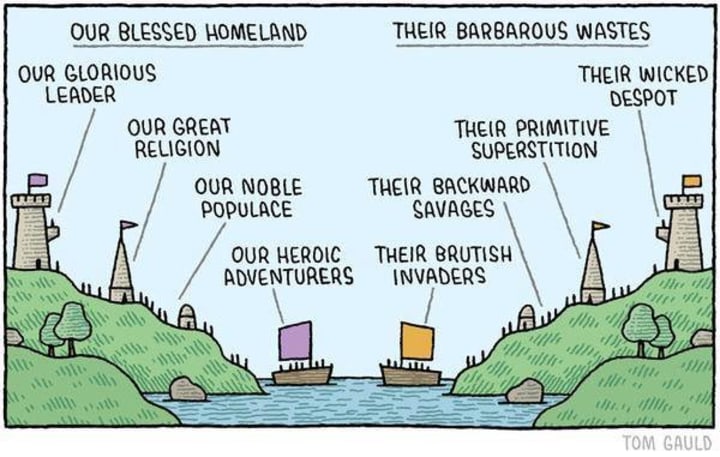

Look at what many of us do. We seek hope in political parties, and brand those who disagree with us as 'idiots'. We look for simple answers to complex issues, and blame others - especially decision makers - when inevitably the answers aren't that simple. We revere strong, powerful, capable leaders, decisive and forceful enough to get things done. We find comfort in the country and culture we know, and grow fearful of those who apparently threaten our peace and calm. We 'worship' cultural idols - pop singers, sports stars, mindful gurus - who seem if not entirely perfect then better than us in so many vital ways.

Before saying "but I don't do that, it's all about them" think carefully about how our thoughts betray those self-same attitudes to our fellow human beings. This speaks for all of us - we have all, at one time or other, sought comfort in groups, and excluded others. Myself included.

Professor Ernest Becker, who flourished in the 1960s and early 1970s, explored the existential reasons why many of us are driven to behaviours that promote group-think, exclude others, and encourage the worship of cultural heroes in his Pulitzer prize winning best seller, "The Denial of Death".

I've written elsewhere about how overcoming our fears of death can lead to increased feelings of connectedness with others across time and space, and how dealing with this repressed fear of death can drive increased motivation to deal with humanity's seemingly intractable challenges. I've also explored a perspective which may help us understand and ultimately deal with our tendency to worship cultural icons and heroes, in an article that showed how "we are prepared to tear each other - and the world - apart for the sake of preserving our immortality wish."

Life and death - the enormity of the world, and our powerlessness to control events within it - drive the transference of our immortality wish onto the strong leader, the political party, and so on. Should something happen to this icon or organisation (as inevitably it must) then we feel threatened by it, deep in our subconscious:

The people apprehend, at some dumb level of their personality: 'Our locus of power to control life and death can himself die; therefore our own immortality is in doubt'

In our continuing efforts to deny death, we immortalise the leader who died by renaming streets after them, building monuments in their image, or clinging even tighter on to the ideologies that they espoused or represented. More so, by transferring our immortality wish onto a powerful figure or group, we attempt to imbue our lives with significance and transcend our perceived limitations.

Humanity is unique in this way, as Becker describes it, by being self-aware, aware of our own impending demise, hence driven by our terror of death. This terror, though denied, is so powerful that it is the 'mainspring' that has driven so many of the cultural manifestations that we are surrounded by, from materialism through exclusion of others to hero worship. Like locusts, we lay waste to the world in order to justify ourselves.

We readily embrace collective delusions that offer a sense of security, meaning, and heroic purpose. This is manifest in phenomena like 'groupthink' and blind obedience to authority. It gives 'permission' for us to participate in destructive acts while displacing responsibility onto leaders or organisations.

We therefore create elaborate worldviews and belief systems to shield ourselves from death anxiety - such as those promoted by political parties, institutions, or cultural movements. While they provide a sense of belonging and purpose, they also fuel intolerance, conflict, and violence through the threat mechanism: whatever threatens our object of transference feels like a personal threat to our own survival.

It is therefore this denial of our own mortality, which we transfer onto others, which in turn perpetuates dangerous and destructive behaviours that bring us ever closer to nuclear annihilation and Armageddon. This profound contradiction can best be addressed to dealing with its root cause: the fear of death.

The articles linked to earlier address this topic in more detail. I will therefore constrain myself to a brief summarisation.

Careful and systematic explorations of the themes found in so-called 'peak experiences' provide profound evidence that challenges very commonly misconceived notions of human reality. The collected evidence - and systematic studies that have been completed to date - show that these themes transcend time and place, culture, personality and background. They show that the reality of human beings persists beyond death, and that this reality connects us, one with another, with bonds that cannot normally be discerned.

While a surprisingly large proportion of adults have themselves witnessed these peak experiences for themselves, a change in perspective does not rely on having had the experience. It is not just personal in such a way that it cannot be shared; on the contrary a careful and systematic sharing of their themes can itself lead to many of the benefits that experiencers themselves have had, most notably a long lasting reduction in the fear of death.

This knowledge of ourselves and each other, by reducing fear, increases the courage needed to connect with each other, across both generational boundaries and geographical divides. Reducing this fear reduces the kinds of irrational prejudice that we have been exploring. This promotes peace by creating the conditions in which human potential can flourish. By helping us to realise that we are by our very nature connected by bonds of unconditional love in oneness, this knowledge of our natures motivates us likewise to take on the challenges, like the spectre of nuclear war, that lay before us.

To hold that the spirit is annihilated upon the death of the body is to imagine that a bird imprisoned in a cage would perish if the cage were to be broken, though the bird has nothing to fear from the breaking of the cage. This body is even as the cage and the spirit is like the bird: We observe that this bird, unencumbered by its cage, soars freely… Therefore, should the cage be broken, the bird would not only continue to exist but its senses would be heightened, its perception would be expanded, and its joy would grow more intense.

The final irony then is that solving our in built contradiction that drives us to destroy ourselves and each other involves overcoming our fears of annihilation.

About the Creator

Andrew Scott

Student scribbler

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.