Allowing Yourself To Be Surprised By The Obvious

Is seeking to describe "happiness" limiting what we can learn from it?

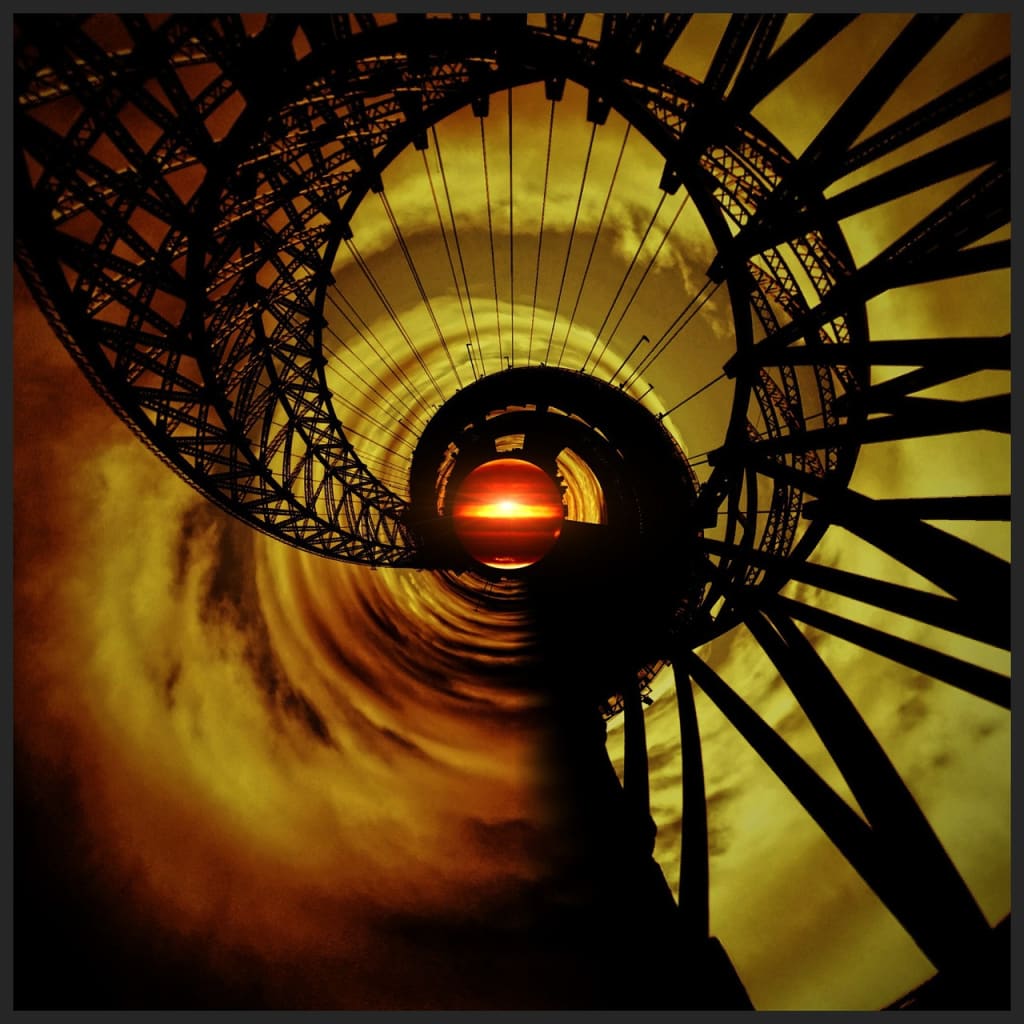

The Awe of It All

Think of a time you were truly captivated by an experience.

Maybe it was something spectacular. Imagine the view from a mountain’s summit after a grueling trek. It could be something more tame, like connecting with a memory through a deeply rooted sense of nostalgia. Perhaps it was the exhilarating moments of inner stillness after leaping from a rocky precipice into the swimming hole thirty feet below. Certainly, and without any implied shame, it could just as easily be time spent watching a particularly engaging Ted Talk.

Words lack the exactitude and particular grandiosity to capture these experiences. With words comes interpretation. Implication. Structure. Tone. These things are all at once separate from the moment itself; arising after-the-fact in the mind like a polaroid camera taking a snapshot (and we know how poorly images tend to represent the scale of the ‘actual’ thing). The conveyance of any personal encounter or feeling is plagued by the shared (or worse: not shared) attachment to the symbols we employ. The predictive brain favors well-identified specificity over considering the ineffable.

However, that well-identified specificity relies on a thousand different synaptic shortcuts accrued over time. As we grow older, the brain gets better at “filling in the blanks,” essentially providing educated guesses as to the nature of our experience in each moment. Instead of stopping to marvel at the jungle gym in a playground, as children might do, we’ve come to understand what place a jungle gym has in our lives and why it’s probably okay to place it lower on the adult priority list.

Offloading our interest in playgrounds makes sense as we mature. But this can go a bit further. There are many who would gasp at the sight of a wide river, weaving through lush meadows of foxtails and lavender beneath a great slope blossoming with rich evergreen trees… but for others, that’s just the dull background on their commute to work.

On one end, there are people encountering genuine awe in situations others deem to be mundane. At the other end, there are those who not only fail to see this grandeur, but actively reject the notion of it. Stop daydreaming, there are more important things to do!

The latter case is a rational endpoint to a societal structure that requires a quieting of sudden, impulsive fascinations. There’s no time, and (perhaps more importantly) no immediate perceived need to ponder the things we do not fully understand. We have a ‘good enough’ assessment of the way things are (at least, we tell ourselves that). We can get to work, raise our children, eat and be entertained on a structured schedule without the flowery pretentions of seeking beauty in things — why rock the boat?

Despite potential resistances, just about everyone knows what it’s like to be truly awe struck. To be left without words, or to feel a deep serenity during an experience. Even the most stubborn can be swayed through a perfect moment of clarity into striving to be a better family member, friend, or individual (at least from their own view — which is key).

In fact, it may be that ineffability and our individualized, phenomenological circumstances provide worthwhile insight regarding the way we interpret ourselves, others, and the world around us. Awe seems to be a critical component to one’s capacity for compassion, ability to affect behavioral change, and sense of satisfaction in life.

The mundanity of that work commute is by all rights its own negative feedback loop patterned around the predictive models of our brain. The more dilute our attention between schedules, phone engagement, and the heightening state of disaffectedness taking root in our day-to-day, the less resources we allocate to fully deriving awe from our surroundings.

You can’t feel what you’re not opened up to sensing.

A Problem With Language

In attempting to advocate for the things we find meaningful, we are liable to trivialize or convolute them in others’ perceptions.

Put another way, laboring to give something a solid form necessarily exposes it to the world of best guesses and conditioned shortcuts mentioned earlier. Now that the indescribable has been condensed into a bite-size dimensional morsel, it can be targeted, compared, criticized, graffitied, slandered, referenced, and categorized in a box alongside everything else in the easy access storage container we call the intellect.

This is often how passion (that has not been tailored for its audience) is quickly dismissed as rambling. First impressions, after all, are notoriously tenacious once adopted.

More insidious, an application of this categorical methodology — either vilifying or sycophantically adulating a given passion — cultivates a biased, looping internal system. As above, so below. Rather: as within, so without. The way we describe something we’ve experienced to ourselves is just as vulnerable to the rigid discernment of our own mind as it is to the judgment of others.

Finding Awe

“Rational people are not doing the things they should be doing to be happier due to misconception.” — Laurie Santos, Making Sense Podcast #196

Laurie Santos is a professor of psychology at Yale University and host to The Happiness Lab (a podcast covering research regarding happiness, wellbeing and quality of life). She is renowned for her study of the variables underlying a “good life,” happiness and positive behavioral conditioning.

The yield of her research has been non-intuitive, to say the least. In fact, intuition — as we tend to employ it — appears to be haplessly ineffectual in guiding us to happier states of mind.

Intuition is the ability to comprehend something without a concerted, conscious effort. Recall the polaroid analogy. Intuition may be compared to a photo book complete with color-coded sections for ease of retrieval. The more we retrieve a specific image, the more habitual its retrieval becomes. We find ourselves turning to the page autonomously in response to an increasing number of situations, extending its range of application. What we practice eventually becomes the contextual basis of our intuition. This is how some are able to correlate the events in their life to an emotional outcome, whether joyful or depressive. “I deserve this,” “I don’t deserve this,” “This is one more reason I should be [happy]/[sad].”

Dr. Alvaro Pascual-Leone, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical, illustrates the metaphor more robustly (an excerpt from “The Brain That Changes Itself,” by Norman Doidge):

“The plastic brain is like a snowy hill in winter. Aspects of that hill–the slope, the rocks, the consistency of the snow–are, like our genes, a given. When we slide down on a sled, we can steer it and will end up at the bottom of the hill by following a path determined both by how we steer and the characteristics of the hill. Where exactly we will end up is hard to predict because there are so many factors in play.”

“But,” Pascual-Leone says, “what will definitely happen the second time you take the slope down is that you will more likely than not find yourself somewhere or another that is related to the path you took the first time. It won’t be exactly that path, but it will be closer to that one than any other. And if you spend your entire afternoon sledding down, walking up, sledding down, at the end you will have some paths that have been used a lot, some that have been used very little.”

The research conducted by Dr. Pascual-Leone and Professor Santos points toward a truth that transcends the superficial into more ineffable territories. The conditioned intuition often sponsors behaviors that act against the grain of scientific markers for happiness, contentment and (by association) awe. The tendency is to prioritize wants over what we would genuinely like. This isn’t cause for self-blame. We may simply lack the tools to track what an emergent “like” scenario would resemble.

You don’t know how you’ll feel after a marathon until you run one.

This notion of precognizant, pre-knowledge fulfillment aligns both with Professor Santos’ research and the Harvard Happiness Study. In a number of studies and meta-analyses dating to the 1930s, researchers have found a spectrum of positive emotional correlates relating to:

- Sincere, earnest perception of others

- Actively wishing wellness / kindness upon friends, acquaintances, and strangers

- Ordinary positive interactions with strangers (e.g. saying hi, thank you, you’re welcome, good day)

These seem obvious.

But that’s the problem with the obvious. It’s out in the open all the time, fully realized on its own. It’s uninteresting. It’s easy to walk around. We assure ourselves there is nothing about the obvious that can surprise us.

Awe is obvious. It’s right there in front of you on the hundred-thousand year technological result of human achievement with which you’re reading this. It’s in the wood of your kitchen table that’s older than you are. It’s in the thousands of miles of raging, merciless wilderness between me and you; and the hundreds of miles of urban empires interspersed therein. We’ve simply practiced blindsight. If we can see that, we can practice lifting the veil again, too.

About the Creator

Bryson Peacock

Writing as communion.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.