Questioning the Effectiveness of Iceland's Beluga Sanctuary in Ensuring Improved Welfare for Cetaceans in Captivity

A new study questions the effectiveness of cetacean sanctuaries for cetaceans living under human care.

In 2019, the SEA LIFE Trust established a beluga sanctuary in Iceland for two female beluga whales, Little Grey, and Little White, moved from Changfeng Ocean World in Shanghai, China. After spending over a year in an indoor quarantine facility, the marine mammals were moved to an open-water sanctuary in Klettsvik Bay the following summer. However, in August 2022, a boat sinking caused oil and fuel contamination in the bay, forcing the whales back to the indoor facility for two years of cleanup and repairs. Despite SEA LIFE Trust's assurances of their return to the sea pen, there have been no updates as of January 2025, raising public concerns about the project’s success and effectiveness.

A January 2025 Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens study, “Cetacean Sanctuaries: Do They Guarantee Better Welfare?” by Javier Almunia and Marta Canchak, scrutinized how well cetacean sanctuaries improve captive whale and dolphin welfare. Focusing on Iceland’s SEA LIFE Trust Beluga Whale Sanctuary and its two beluga residents, Little Grey and Little White, the study detailed the challenges of rehabilitating these whales into a natural, yet still human-managed, environment. The Trust aimed to provide a more natural environment but encountered difficulties.

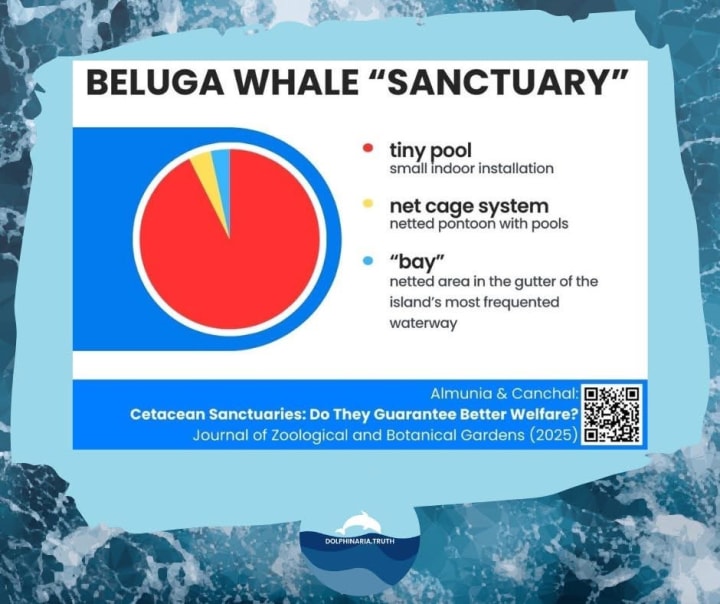

The Icelandic Beluga Sanctuary project faced many hurdles. The whales spent most of their time (92.6%) in an indoor facility because of the cold bay temperatures, which required careful weight management to ensure adequate blubber for thermoregulation. Acclimation to the open-water habitat was also problematic, causing distress and mild bacterial stomach infections, which delayed their transfer. Additionally, a contractor's diving boat sank, causing oil and fuel contamination, further impeding the project's effectiveness.

The study highlights that, because of these challenges, Little White and Little Grey spent a significant portion of their time in a conventional indoor poor than they did in the open-water sanctuary. The authors concluded that while cetacean sanctuaries are often viewed as a “middle ground” between human care and full release, the complexities that were observed at the Beluga Whale Sanctuary show that sanctuaries may not always guarantee improved welfare for cetaceans. They emphasized the need for refined sanctuary models, improved infrastructure, and structured adaptation programs that are tailored to the specific needs of individual animals to ensure their welfare.

The study questions the common belief that moving captive cetaceans to a more "natural" marine environment automatically improves their welfare. This idea, driven by public opinion and philosophical opposition to keeping marine mammals in captivity, suggests that sea contact—even in enclosed areas—inherently improves their quality of life compared to pools. However, the authors argue this is unsupported by scientific evidence and should be considered speculation. They point out that transitioning cetaceans from sterile, concrete pools to natural sea pens introduces potential stressors like fluctuating water quality, exposure to marine pathogens, and severe weather. These factors can negatively affect both animal well-being and potentially disrupt local marine ecosystems.

Several attempts have been made to create cetacean sanctuaries as alternatives to conventional enclosures, but many of these projects remain unfinished or lack the authorization and infrastructure. For example, The Whale Sanctuary Project (launched in 2015) currently consists only of a shop and interpretation center, with no animal habitat or established construction plans. The National Aquarium in Baltimore proposed a dolphin sanctuary in 2014 but abandoned the plan in 2019 because of climate concerns. While the idea has been revisited, no location or plans have been disclosed. The Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary (started in 2015) has offices and veterinary facilities but lacks holding pools and authorization to construct sea pens.

The SEA LIFE Trust’s Beluga Whale Sanctuary and recent studies highlight the difficulties of improving captive cetacean welfare through sanctuaries. Although sanctuaries appeal to the public desire for humane marine mammal treatment, the Icelandic project shows that transitioning cetaceans to natural environments presents logical, environmental, and welfare obstacles. Sanctuaries need to move beyond good intentions to create scientifically based frameworks that address individual animal needs. As the debate on keeping captive cetaceans continues, these lessons should inform future sanctuary efforts to improve the animals’ quality of life and minimize harm.

Source:

Almunia, J., & Canchak, M. (2025). Cetacean sanctuaries: Do they guarantee better welfare? Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 6(1), 34-47. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-5636/6/1/4

About the Creator

Jenna Deedy

Just a New England Mando passionate about wildlife, nerd stuff & cosplay! 🐾✨🎭 Get 20% off @davidsonsteas (https://www.davidsonstea.com/) with code JENNA20-Based in Nashua, NH.

Instagram: @jennacostadeedy

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.