Genetic Health Testing

Its value and its limitations

Every so often, I like to come back to the idea of genetic health testing. There's so much to talk about that I'm certain this won't be the last time. Health testing is a big deal in dog breeding. Before we had access to canine DNA, breeders were trying to improve breed health through hip x-rays and cardiac/stress testing, usually performed in a veterinarian's office and eye/vision and ear/hearing tests, often performed at dog shows. Careful pedigree analyses were made to prevent or at least reduce inbreeding. Conscientious breeders avoided pairing dogs with extreme body types or visible flaws. Pedigree research can still give us a better understanding of where certain traits were established and of what recessive genes might be lurking, undetected due to markers not yet being established for them, but understanding a dog's pedigree is now only part of being a responsible and ethical breeder.

The end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century saw the marked shift in the understanding of hereditary traits. It cannot be said enough that, if a breeder pays attention to all of these external features (the phenotypical traits) and then gains understanding of these features through supporting them with genetic information (the genotypical traits), a better breeding program can be formed. This kind of informed breeding can result in healthier dogs. Of course, it's not enough to have awareness of any of these things. Any testing of any kind is only useful if the breeder acts upon the information that they've received.

How do Breeders use DNA Testing?

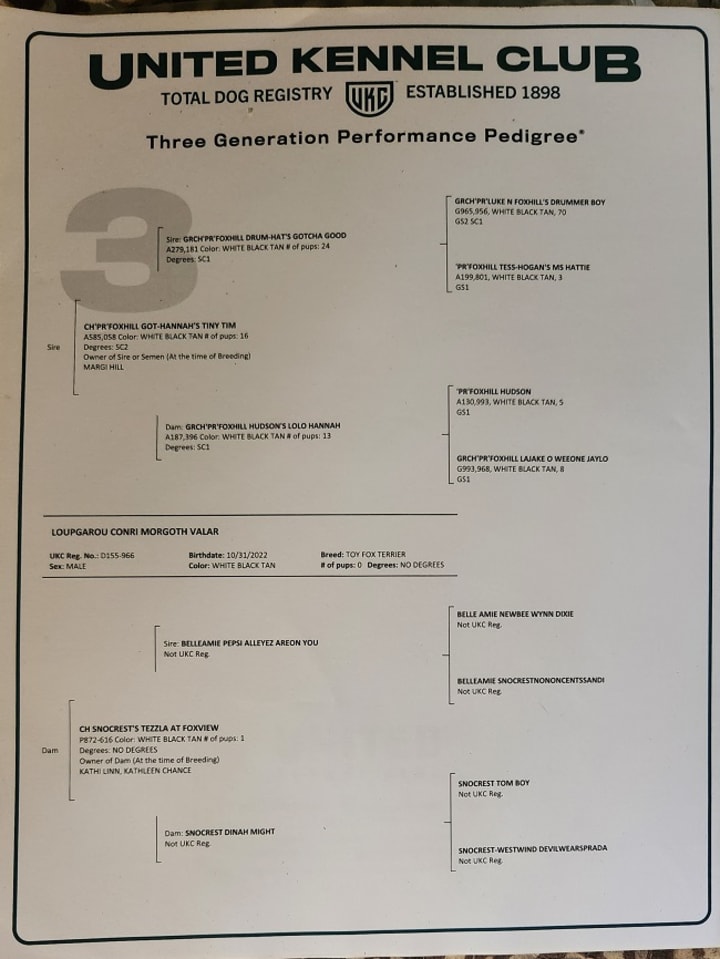

For the individual breeder, genetic testing is an ongoing process as new dogs--and new traits--move into the breeding program. Kathleen and I believe that every dog needs its own "paperwork," even if the sire and dam were previously tested and show up clear. New diseases, syndromes, and conditions are identified all the time and recessive genes or previously unknown genetic mutations can emerge over generations. We recently tested a dog whose parents tested clear on all major issues for the breed. This dog did, too, but it turned up carrying a gene that had previously appeared only in the one of its ancestral breeds. It's not an issue for the dog's continued health. Neither will the health of its puppies be affected. The dog is an excellent example of its breed and is a candidate for "breeding for replacement." The gene is simply one we must watch for and breed carefully around to eliminate it from our gene pool.

In order for a dog breeder to properly utilize genetic testing, he or she must be familiar with the breed standard and health profile for the breed in question. Not all genetic alerts are of equal importance. Learning to identify the breed's problem areas, as well as learning to work with or around them, is the fault of living in a technological age--as well as the fault of animal rights activists, but that's another article. It's not that dog breeds are unhealthier than they were (although, some are), it's that we have more ways of determining why a dog might be what our ancestors may have called "unthrifty" or "a hard keeper." Although rudimentary understanding of hereditary traits existed in early breeding efforts, decisions were often based on a dog's instinct, it's external features such as coats or leg length or type of ear, particularly when developing a type or a breed. Failures were often thought to be physical in nature, linked to hard use as working dogs. For example, when a dog lost the use of its hind legs as it aged, people once blamed "hips," without thinking of other causes.

At the time, we had no idea that it could be anything else. We only had hip x-rays to give us information. Even PennHIP was about 30 years in the future. Looking back, my grandfather's German Shepherd Dog developed symptoms that I now suspect, 50 years later, were indicative of degenerative myelopathy (DM). If I had Champ's pedigree in front of me today, as well as pedigrees and breeding records of GSDs who were in existence at that area at that time, I might be able to establish who the dogs were that produced puppies with similar symptoms as they aged. I could trace it down generations and determine to a degree whether the trait had genetic factors or whether it was based on environmental factors. Unfortunately, that kind of information provided only post facto information, after the dog was mature or after several generations of breeding had produced serious issues. Genetic testing, for all its flaws, can be done as soon as the puppies are weaned. That ability gives the breeder a big jump on the decision-making timeline.

Issues with Genetic Testing

Genetic health testing can be an arduous affair. It's slow. It's expensive. Sometimes, it means shopping different labs for tests for which your "regular" lab has no test. As with anything else, some laboratories are better at testing than others. Some tend to take a scattershot approach to testing, performing all tests on every individual sample, regardless of whether a marker appears for the trait or condition in the breed or not. This approach can be helpful in the long run, as it might help identify outliers in the breed who are affected by a previously unknown problem. Other laboratories prefer to specialize in breeds or traits or regions. Some laboratories only offer individual tests, which can be grouped for a profile on individual dogs. Finding a single laboratory that meets all the needs of a particular breed can be slow and sometimes difficult. Still, it's a darn sight better than when we first started testing and had to go to the individual scientists who were developing their own specialized tests for the traits. *Shout out to Dr. John Fyfe (Michigan State University) who pioneered congenital hypothyroidsim with goiter testing in the Toy Fox Terrier. His actions saved many a future TFT puppy.*

In addition, there are times when a lab simply can't process a sample properly. I should note that the breeder is almost always the weak link in all of the laboratory testing issues. Labs have protocols that usually prevent sample contamination or loss. However, when you're by yourself wrestling with a 25-pound Teddy Roosevelt Terrier who has suddenly grown four additional legs that are all pushing against you at the same time, things can happen. One time, I actually mixed up two samples that were being processed at the same time. Fortunately, the dogs were of two different breeds, so when a Teddy came back as a TFT, I knew I had a problem! In any case, on occasion, I've found a post in my account: "Unable to Process." The labs have been awesome, sending new brushes and allowing me a second chance to wrestle canine Sleipnir into submission.

Other Benefits of Testing

One fascinating thing about dog genetic testing is that it can help human beings. Scientists can develop models for testing based on canine genetics, giving insight into human diseases. One good example of this process is how the testing done on Bedlington terriers for liver disease led to insight on two different diseases in human beings.

Copper Toxicosis and Wilson's Disease

Bedlington terriers are prone to liver disease. When genetic testing became available, responsible breeders tried to seek out why it was occurring. They found, after a lot of work with animal geneticists, that Bedlingtons have a genetic flaw that prevents normal copper storage in their livers. Basically, they were getting poisoned by normal levels of copper in their diets! While many Bedlingtons are still plagued by the problem, breeders have been able to test their dogs and selectively breed away from the problem, lessening its impact over time.

The really neat thing about this is that, while breeders might have perceived this storage issue to be a singular issue in the breed, other dogs and mammals--including humans--can be plagued by copper toxicosis! Molecular biologists were working with rats to build potential models for understanding both Wilson's disease and (Asian) Indian childhood cirrhosis. However, the genetic testing on Bedlington terriers provided insight into the genetic mapping, as well as the defects, for both. It turns out that the Teddy Roosevelt Terrier might well be on the fringes of affected breeds, so it's something new for which we Teddy breeders must establish awareness.

Overall, genetic testing has more benefits than drawbacks when used in dog breeding. It's a tool that is continuously evolving and finding new discoveries that can help us improve the health of our beloved dogs. While there will never be a perfect dog in existence, whether genetically or in terms of the breed standard, DNA testing helps us move ever closer to that impossible ideal.

About the Creator

Kimberly J Egan

Welcome to LoupGarou/Conri Terriers and Not 1040 Farm! I try to write about what I know best: my dogs and my homestead. I'm currently working on a series of articles introducing my readers to some of my animals, as well as to my daily life!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.