The "Pervert" Who Saved Millions: The Bloody Truth of the Pad Man

Subtitle: He lost his wife, his mother, and his dignity to solve a problem no man dared to talk about. This is the raw story of Arunachalam Muruganantham.

The true story of Arunachalam Muruganantham, the man who wore a sanitary pad, lost his family, and endured public shaming to spark a menstrual hygiene revolution in India.

Introduction: The Man With the Bloody Bladder

Imagine a man walking through a village in rural India. It is 100 degrees Fahrenheit. He is sweating. He is walking funny, shifting his hips uncomfortably.

Underneath his clothes, he is wearing a sanitary pad.

Strapped to his waist is a hollowed-out football bladder filled with goat’s blood. A tube runs from the bladder to his underwear. Every time he walks, he squeezes a pump, forcing the blood onto the pad.

He is doing this to test absorption rates.

He smells like copper and sweat.

He looks insane.

The villagers don't call him an inventor. They don't call him a hero.

They call him a pervert. They call him a sexual deviant. They hide their daughters when he walks by.

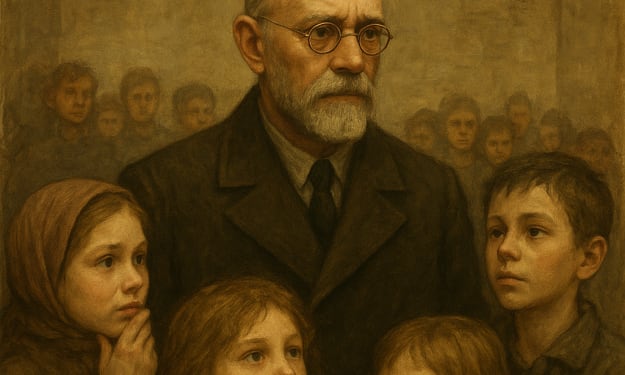

This is Arunachalam Muruganantham.

Today, he is listed as one of TIME Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People. He is the subject of Bollywood blockbusters and Oscar-winning documentaries.

But before the red carpets and the TED Talks, he was just a school dropout who lost everything—including his wife and his mother—because he dared to touch a subject that was considered "dirty."

This isn’t a story about a business. This is a story about the price of caring.

Part I: The Dirty Rag that Started a War

It started in 1998, in Coimbatore, South India.

Muruganantham was newly married. One day, he saw his wife, Shanthi, hiding something behind her back. She was trying to be discreet.

He asked what it was. She refused to show him.

He insisted.

What he saw shocked him. It was a rag. A nasty, dirty, blood-stained cloth that she had been washing and reusing for months.

He asked her, "Why are you using this? It’s unhygienic. You’ll get an infection."

Her answer was a slap in the face of reality:

"If I buy sanitary pads for myself, we won’t have enough money to buy milk for the family."

That was the math. Milk or hygiene. You couldn't have both.

Muruganantham went to the local pharmacy. He bought a pack of pads. He held it in his hand. It felt like cotton. It weighed nothing.

Then he looked at the price.

The raw materials cost pennies. The selling price was 40 times higher.

It wasn't a product; it was a robbery. The multinational corporations were making a killing on women’s shame.

He decided then and there: I can make this cheaper. I can make this safer.

He didn't know he was about to ruin his life.

Part II: The Rejection

He started simple. He bought cotton. He cut it into rectangles. He wrapped it in thin cloth.

He made a prototype.

He gave it to his wife.

"Test this," he said.

She tested it. And she gave him the feedback that every inventor fears:

"It’s useless. I’m going back to the rags."

The cotton didn't absorb. It leaked. It was a mess.

He needed to know why. He needed to test different materials.

But he had a problem. His wife only had her period once a month.

Waiting 30 days for feedback was too slow.

He needed more volunteers.

In rural India, asking a woman about her period is like asking for her banking password while holding a gun. It is taboo. It is silent. It is "impure."

He asked his sisters. They kicked him out of their house.

He went to a local medical college. He begged female students to test his pads. They looked at him like he was a predator. Some agreed, but were too shy to give real feedback.

One day, he found his prototypes in the trash bin. The students hadn't even used them. They were too embarrassed to be seen with his "home experiments."

He realized then: No woman is going to help me.

If he wanted to solve this, he had to become the user.

Part III: The Descent into "Madness"

This is where the story separates the hobbyists from the obsessed.

Muruganantham decided to wear the pads himself.

He built the "uterus" out of the football bladder. He filled it with goat blood mixed with an anti-coagulant to stop it from clotting too fast.

He wore it for days. He walked. He cycled. He ran.

He felt the wetness. He felt the chafing. He felt the humiliation of a leak staining his trousers in public.

He was a man in his 30s, washing blood-stained underwear at the village well.

The village turned on him.

Rumors spread like wildfire.

* "He is doing black magic."

* "He is suffering from a sexually transmitted disease."

* "He is a vampire."

* "He is a pervert chasing women."

He didn't care about the village. He cared about his wife.

But the pressure was too much for Shanthi.

She couldn't walk down the street without people mocking her husband. She couldn't visit her family without them telling her to leave him.

She begged him to stop.

He refused.

So, she did the only thing she could to save her own dignity.

She left him.

She packed her bags and went back to her mother’s house. She filed for divorce.

A few months later, his own mother walked out on him. She couldn't stand the shame of having a son who washed bloody rags.

He was alone.

He was living in a shed.

He was eating on the floor.

The world had declared him a failure.

Part IV: The Secret of the Pine Wood

Most men would have quit here.

Your wife is gone. Your mom is gone. You are the village joke.

But Muruganantham was possessed by a question: Why do the corporate pads absorb, and mine don't?

He sent samples of the corporate pads to a lab. The results came back: It wasn't cotton.

It was cellulose derived from pine wood pulp.

It was a specific material that swelled when wet, locking the liquid inside.

The problem? The machines required to process pine wood pulp cost $500,000. They were massive industrial monsters imported from the West.

That’s why the pads were expensive. The barrier to entry was half a million dollars.

Muruganantham didn't have $500,000. He had a welding torch and a brain that wouldn't quit.

He spent four years re-engineering the process.

He broke it down.

* A machine to de-fiber the wood pulp.

* A machine to compress it into shape.

* A machine to sterilize it with UV light.

He built a machine that did exactly what the million-dollar plants did.

But his machine was simple.

It was manual.

It was the size of a refrigerator.

And it cost $950.

He had done the impossible. He had democratized the technology of hygiene.

Part V: The Anti-Capitalist

When he finally produced a perfect pad—one that was sterile, absorbent, and cost 2 rupees instead of 10—the sharks started circling.

He showed his invention at IIT Madras (India's MIT). The scientists were floored.

His innovation won the National Innovation Award from the President of India.

Suddenly, the "pervert" was a genius.

Corporate investors called him.

"We will buy the patent," they said. "We will give you millions. Just sign here and we will handle the distribution."

He could have been rich. He could have bought the biggest house in the village and laughed at everyone who mocked him.

He said no.

He realized that if he sold the patent to a corporation, they would just use his machine to make cheap pads and sell them for a high profit. The price for the women wouldn't drop. The cycle wouldn't break.

He didn't want to make money. He wanted to make change.

He open-sourced the design.

He refused to trademark it.

His business model was radical: He sold the machines directly to rural women's self-help groups.

* He gave them the machine.

* He gave them the raw pine wood pulp.

* The women made the pads themselves.

* They sold the pads to other women in their village.

It was a double victory.

* Women got cheap pads.

* Women got jobs.

He wasn't just solving hygiene; he was solving poverty.

Part VI: The Redemption

Today, Muruganantham’s machines are installed in 23 of India's 29 states. They are in 106 countries around the world.

He has created thousands of jobs for women who previously had no income.

Millions of women who used dirty rags, ash, or newspapers now use sterile pads.

And the village?

The village that called him a pervert now calls him "The Legend of Coimbatore."

But the most important return wasn't the fame.

Five years after she left him, Shanthi called him.

She saw him on TV. She saw the award. She realized that his madness had a purpose.

She came back.

His mother came back.

He accepted them. He didn't hold a grudge. He understood that society had blinded them, just as it blinds us all.

Part VII: The Uncomfortable Lesson

Arunachalam Muruganantham is not a typical CEO. He still wears simple clothes. He speaks broken English. He drives a modest car.

He travels the world telling people one thing:

"Don't chase money. Chase problems."

His story is a violent correction to the modern idea of "entrepreneurship."

We think entrepreneurship is a laptop, a coffee shop, and a pitch deck.

Muruganantham shows us that real entrepreneurship is suffering.

It is being willing to look like a fool.

It is being willing to lose your status.

It is being willing to stand alone in a room, wearing a football bladder of blood, because you know that if you don't solve this, nobody else will.

Conclusion: The Man Who Wore the Shame

Why does this story matter?

Because menstruation is still a stigma. In many parts of the world, women are banned from temples, kitchens, and schools during their periods. They are treated as "untouchable."

Muruganantham didn't just invent a machine. He invented a conversation.

By acting like a "pervert," he forced society to look at what it was hiding.

He forced men to say the word "period."

He forced husbands to buy pads for their wives.

He took the shame onto himself so that millions of women wouldn't have to carry it anymore.

He proves that you don't need a PhD to change the world. You don't need millions of dollars.

You just need the courage to care about something that everyone else ignores.

And you need the guts to keep walking, even when the whole world is laughing at you.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.