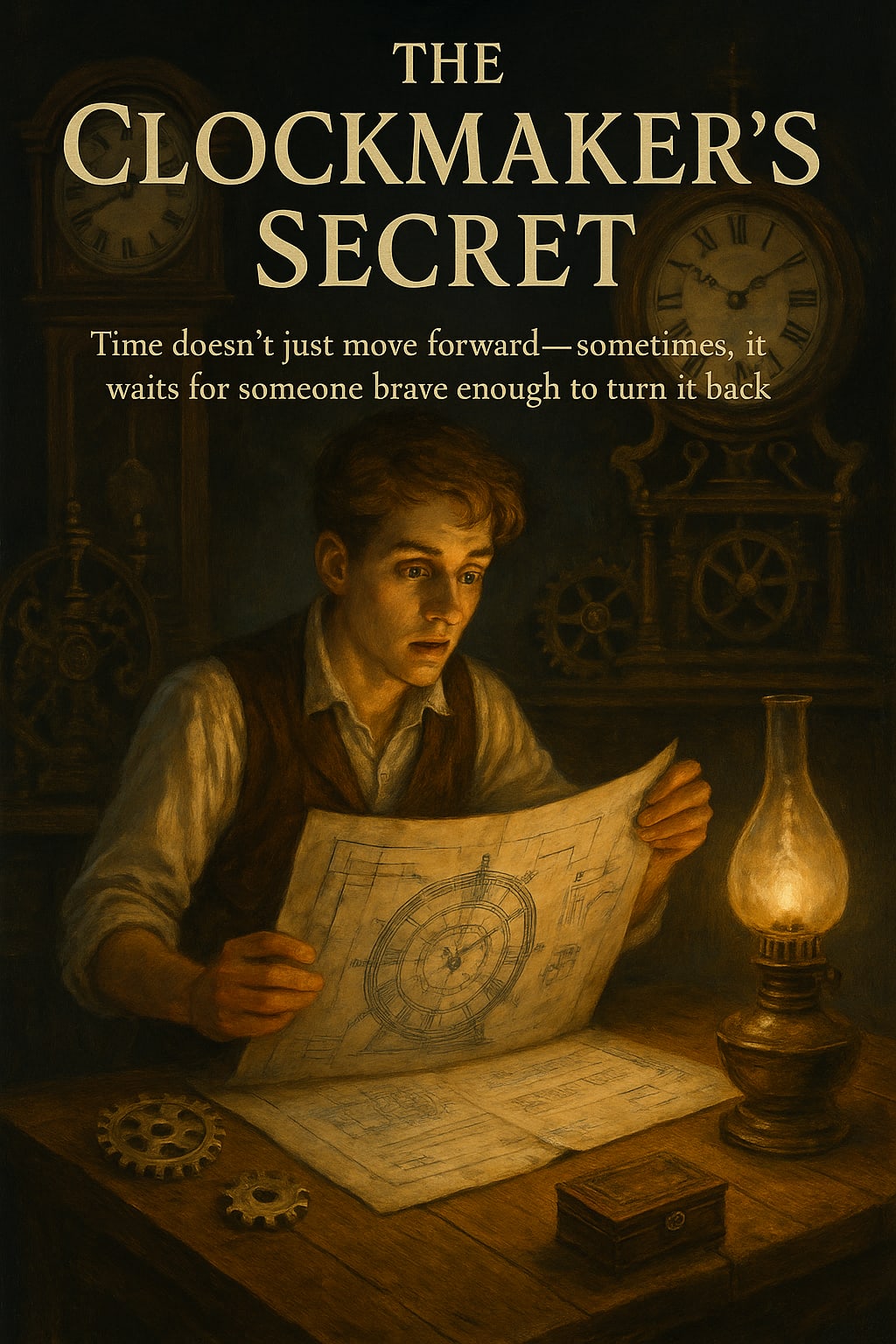

The Clockmaker’s Secret

Time doesn’t just move forward — sometimes, it waits for someone brave enough to turn it back.

London, 1889

The air inside Thatcher’s Timepieces always smelled of oil and old wood. Gears clicked softly in the background like whispering voices. Henry Lane, age 17, had worked as Mr. Thatcher’s apprentice for three years, and though he’d swept every inch of the shop, there was one thing he’d never seen: what was inside the old oak cabinet marked PRIVATE.

Mr. Thatcher was a peculiar man—brilliant with machines, cold with people. He didn’t speak much, except when he explained how time worked. Not as a straight line, he’d often say, but as a circle waiting to be cracked open.

The day Thatcher died, everything changed.

Henry found him slumped at his desk, hand resting over an open journal and a strange brass gear clenched in his fist. A gear with 13 teeth — an impossible number in any known clock mechanism.

The constables came and went. The death was ruled natural. But Henry couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong. Thatcher had always feared something. He’d lock the door even in daylight, and his eyes always lingered on the large grandfather clock that stood silent and unwound.

With the shop now his, Henry did something he had never dared.

He opened the PRIVATE cabinet.

Inside were stacks of yellowed blueprints, broken watches, and at the very back — a small, locked box. It had no keyhole, only a narrow slit that looked exactly the size of the strange gear Thatcher had clutched.

Henry inserted it.

Click.

The box opened.

Inside was a folded letter:

> To whoever finds this,

I was wrong. Time is not bound by our laws. I have seen it move backwards. This gear is the key to a machine that was never meant to work — and now it does.

It must never be started.

– R. Thatcher

And beneath the letter: a blueprint titled Chronoportus: Mark I.

---

That night, Henry worked by candlelight, reconstructing the machine from the blueprint. The pieces were all there — buried in the backroom, forgotten under cloth and dust. It took him three days to assemble it: a large, clock-shaped device with dozens of spinning arms, a seat in the center, and a dial labeled with dates instead of hours.

He powered it with the gear. The moment it clicked into place, the machine hummed with unnatural life.

On impulse, Henry set the dial to March 4th, 1885 — the day his little sister, Anna, died of fever. He had always blamed himself for playing in the river that week, even though the doctor swore it wasn’t related.

He pulled the lever.

The world shuddered. The ticking of clocks around him halted — then resumed, all at once, backward.

---

Henry woke in his childhood bedroom. He could hear Anna’s laughter in the next room. It worked.

For two days, he lived again in that time. He warned his mother of the fever symptoms. He kept Anna indoors. By the week's end, she was alive and healthy.

But when he tried to return to the machine — hidden beneath Thatcher’s shop, which didn’t yet exist — it was gone.

Time would not let him leave.

---

Months passed. Years. Henry grew up again. He watched steam give way to electricity. He never built clocks. He never found Thatcher.

But one day in 1912, as a gray-haired man, Henry passed by a curio shop in London and froze.

In the window was the 13-toothed gear.

And inside, working the register, was a boy who looked just like a young version of himself.

---

Henry stepped inside. The boy looked up, startled.

"Can I help you, sir?"

Henry smiled sadly. "No. But I can help you."

He handed him a small, worn box. The same box that once opened everything.

"You’ll find your answers in there. Just don’t forget — time is a gift, not a toy."

And with that, he vanished into the fog.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.