Octavia E. Butler’s Positive Obsession

Using mind control to achieve purpose against the odds

Octavia E. Bulter’s writing is known for its strident and tangible female characters, of which there have been historically few in the genre of science fiction.

I’ve looked to her protagonists for guidance since I first picked up Parable of the Sower as a teenager: In the Earthseed series, Lauren taught me the benefit of returning again and again to community; in Dawn, Lilith transformed how I view humankind’s relationship with other living creatures; in Wild Seed, Anyanwu showed me what it looks like to heal together from trauma; in Fledgling, Shori reminded me of the fundamental grounding of family and kin; and in Kindred, Dana found resilience in the face of volatility and injustice.

Despite this wealth of role models, more often than not, I turn to the author herself for advice and inspiration.

In Positive Obsession, an essay in her short story collection Blood Child and Other Stories, Butler wrote that at its best, science fiction stimulates our imagination and creativity. "It gets reader and writer off the beaten track, off the narrow, narrow footpath of what 'everyone' is saying, doing, thinking--whoever 'everyone' happens to be this year." Her writing has done just that for me, and countless others.

In a post-script reflection on this essay though, Butler said, “I have no doubt that all the best and the most interesting parts of me is my fiction.” Here, I have to disagree.

Butler’s writing may have changed how I see and interact with the world, but it was Butler herself who changed me.

My Negative Obsession

The first time I read Positive Obsession, I had been searching for an answer to my own negative obsession. My mind, when presented with open space, had/has a tendency to fill it with worry or self-undermining ridicule (stuff I would never say or think about other people).

There are moments that I’m more susceptible to this negative obsession, such as falling asleep at night, seeing something that reminds me of a past pain, and pretty much any time after (and for years following) public speaking.

When I reflected on this at a retreat a few years back, author Julie Pham described it as “spinning.” And the truth is, my spinning costs me time, sleep, health, and life. I knew I shouldn’t keep reliving the negative, but until reading Positive Obsession, I had no idea how to get off that train.

The Destructive Assumption

If you haven’t read Blood Child (or Butler’s other books), particularly if you’re a writer or a human experiencing modernity, I recommend every page. Positive Obsession is a personal favorite, because in it, Butler gave a glimpse into her journey to becoming a full-time writer, as well as a roadmap for wielding obsession for our own good.

She reflected on the first time she entered a bookstore, after practically living in the library and owning some hand-me-down books. Having saved up five dollars, she entered the bookstore full of “vague fears” and eager to buy a new book that she herself had chosen, and one which she could keep.

“Can kids come in here?” I asked the woman at the cash register once I was inside. I meant could Black kids come in. My mother, born in rural Louisiana and raised amid strict racial segregation, had warned me that I might not be welcome everywhere, even in California.

The cashier glanced at me. “Of course you can come in,” she said. Then as though it were an afterthought, she smiled. I relaxed.

For Butler, as was the case with her protagonists, the world presented longshot odds and structural injustice. Thankfully, she was too positively obsessed to let reality derail her. Many of her characters also shared her steadfast trait, shown in this excerpt of dialogue between Butler and her aunt.

“I want to be a writer when I grow up,” I said.

“Do you?” my aunt asked. “Well, that’s nice, but you’ll have to get a job, too.”

“Writing will be my job,” I said.

“You can write any time. It’s a nice hobby. But you’ll have to earn a living.”

“As a writer.”

“Don’t be silly.”

“I mean it.”

“Honey… Negroes can’t be writers.”

“Why not?”

“They just can’t.”

“Yes, they can, too!”

I was most adamant when I didn’t know what I was talking about. In all my thirteen years, I had never read a printed word that I knew to have been written by a Black person. My aunt was a grown woman. She knew more than I did. What if she were right?

I’m grateful to have grown up in a world where writers like Octavia Butler, Anne McCaffrey, and Sheri Tepper were available in my library and on our family bookshelf; they make it easier to think of myself as someone who can be a writer. They make it easier for women to be writers.

Thanks to them, I don’t have to struggle against a genre or industry that doesn’t want me. I have only to struggle against myself, and the doubts that take root when I allow myself to spin.

Butler didn’t have that luxury though. There was no proof that Octavia’s obsession could pay off, and plenty of reasons to believe it would not.

Why aren’t there more Science Fiction Black writers? There aren’t because there aren’t. What we don’t see, we assume can’t be. What a destructive assumption.

In addition to the societal norms vying to steer her away from writing, Butler’s own internal “spinning” had things to say about herself:

I believed I was ugly and stupid, clumsy, and socially hopeless. I also thought that everyone would notice these faults if I drew attention to myself. I wanted to disappear. Instead, I grew to be six feet tall.

Doubts, Octavia tells us, show themselves in all sorts of ways. She exemplified though that doubts can be transformed. Doubt may be chiseled into a powerful and positive obsession.

Finding the Target

In introductory remarks that she gave at MIT for a discussion on science fiction and modern culture, Butler reflected on the moment she realized she wanted to be a science fiction writer: while watching a terrible movie called, “Devil Girl from Mars.” In the film, the men of Mars have died off and a female Martian comes to earth to bring more men back for the remaining Martians.

As young Octavia watched, she had a number of revelations:

The first was that "Geez, I can write a better story than that."

And then I thought, "Gee, anybody can write a better story than that."

And my third thought was the clincher: "Somebody got paid for writing that awful story."

So I was off and writing, and a year later I was busy submitting terrible pieces of fiction to innocent magazines.

Like Butler, I took an interest in writing at a young age; though for me, it was sparked by a book about rainforests. There, mixed in amongst the pages of lush trees and warnings of deforestation, I first learned about the toucan, and more specifically, the bills of toucans. Their astoundingly large beaks inspired my first writing as a child, in a series of “books” starring Squeaky the Toucan (published in Elmer’s glue bound single print editions by Reid Elementary School).

Throughout Octavia’s home and notebooks, she posted motivational messages and reminders helping her keep aim. On the back of one such notepad, she wrote:

I shall be a bestselling writer. After Imago, each of my books will be on the bestseller list of LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My novels will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them hard or not, whether I’m paid a high advance or not, whether I ever win another award or not… my books will be read by millions of people! So be it! See to it!

She described this approach in Positive Obsession, defining obsession from her old Random House dictionary as, “the domination of one’s thoughts or feelings by a persistent idea, image, desire, etc.” More often than not, society thinks of obsession in the negative sense (my “spinning” for example), but Butler saw opportunity in obsession, if it could be used positively.

Using it is like aiming carefully in archery… I saw positive obsession as a way of aiming yourself, your life, at your chosen target. Decide what you want. Aim high. Go for it.

To help me take aim, I use a tool that wasn’t available when Butler was writing: the Passion Planner. Every year, month, and quarter, it prompts me to reflect upon my priorities and passions:

After using Passion Planners for the better part of a decade, I’ve amassed a wealth of self-reflection on where I’m able to meet goals and where I miss the target. At the end of 2020, I reviewed years’ worth of these reflections and found a persistent theme:

- When asked whether I was happy with how I spent my time, I almost always said: “I didn’t write enough.”

- When asked what I could improve on in the coming month, I almost always said: “Write every day.”

Month after month, year after year, I had taken note of the gap between what I was taking aim at (becoming a writer) and what I was (a person obsessively spinning about how they could fail as a writer). Seeing this trend so clearly laid out helped me initiate a change.

With Octavia's roadmap, I identified my positive obsession: write every day.

The pages of my Passion Planners and the back of Butler’s notepad show the bullseye we each had in view. But aiming an arrow isn’t the same as firing it or hitting the target.

Firing the Arrow

For a while, Butler did just as her aunt had suggested. She worked to pay the bills and wrote to feed her obsession.

I got up at two or three in the morning and wrote. Then I went to work. I hated it, and I have no gift for suffering in silence. I muttered and complained and quit jobs and found new ones and collected more rejection slips.

In response to Butler’s disciplined obsession, she was met for years by rejection from publishers. Moments of affirmation were few and followed by periods of apparent stagnation.

I was twenty-three when, finally, I sold my first two short stories… I didn’t sell another word for five years.

For me, barren stretches with no positive feedback offer endless opportunities for spinning. Octavia Butler modeled an alternative to this mentality: Become so obsessed with your desired vocation that there is no option but to continue toward it, despite evidence suggesting such a thing may be foolhardy. In other words, make spinning obsolete.

Positive obsession can supersede rejection slips, cultural norms, and even paralysis-inducing doubt.

Mind Control

While discussing Positive Obsession in a recent writing group, fellow writer Norea Hoeft commented that “to persist toward a vision that no one else is validating does require us to become a little insane.”

Octavia’s Positive Obsession essay articulated a structure for this insanity: mind control. Not mind control like Mary the Patternmaster or Wanda the Chaos Witch might employ in fictional tales. Rather, self-mind control: the dominance over our own thoughts and doubts.

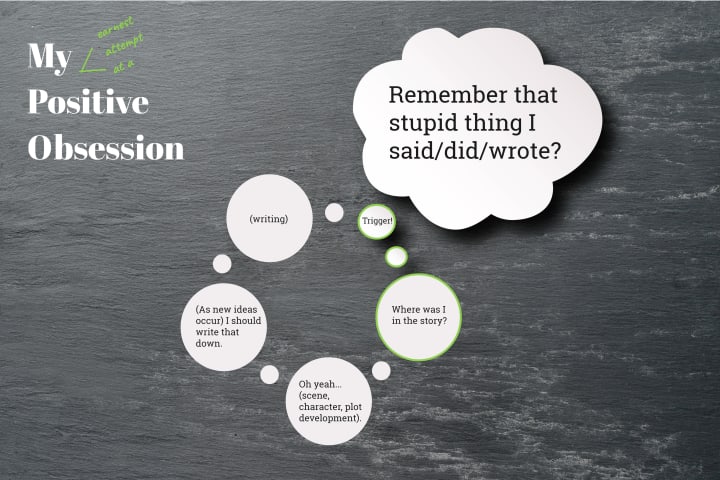

For myself, I’m working to turn my moments of negative obsession into a trigger: when I find myself spinning, I try to interrupt the thought and refocus the (often emotional) momentum toward my positive obsession: writing.

When I succeed, my mind is like a train switching tracks. The engine is still moving, but its heading in an entirely new (and much more productive) direction.

At first, this was just a method to stop my negative thought cycle. After a few years though, I’ve come to rely on pre-sleep to discover key elements of characters and scenes. Most days now, I wake up early enough to write before work, often jotting down the ideas I cooked up the night before. Starting days with my positive obsession also gives me a sense of a “win.” For no matter what else this day might bring, at least I got to write.

Does this make me less critical of myself? Perhaps not, and maybe that’s ok. But overall, I’m spending less time on self-condemnation, and more of it doing better this next time around.

Hitting the Bullseye

Octavia’s resolute obsession was with becoming a writer of science fiction, a target she hit in her 30's. She would later go on to be honored with many awards, including being the first science fiction author to win the MacArthur “Genius” fellowship; and just as she hoped, readers eventually flocked to her stories regardless of these honors.

She lived to see her goal of making lists for L.A. Times Bestsellers and Publisher’s Weekly Best Books, and 14 years after her death, Parable of the Sower would finally make the NYT Bestseller list. Today, an asteroid, a mountain on a moon of Pluto, and an LA maker-space carry her name.

Even as I write this, the Perseverance rover is taking its first test drive on Mars, departing from a touchdown site that mission team scientists have informally named the “Octavia E. Butler Landing.” Butler may be gone, but her stories continue to reshape our narrative.

Bylines and Precedent

At the time of her writing Positive Obsession, Butler noted that, “As far as I know, I’m still the only Black woman who does this.” That isn’t the case today, and Butler played a critical role in changing that. In addition to her personal goals, Butler focused her obsession on overcoming genre and systemic barriers to Black writers. On the back of a notepad, she wrote:

I will send poor black youngers to Clarion or other writer’s workshops. I will help poor black youngers broaden their horizons. I will help poor black youngers go to college.

Here too, Octavia is hitting her target, though sadly she’s not around to read the manifestation of it. In their book exploring the influence and legacy of Octavia Butler, author Nisi Shawl and scholar Rebecca Holden wrote:

Butler herself crossed many boundaries—perhaps to ensure a certain kind of survival for herself and her ideas of what we might become. In the most obvious of these boundary crossings, she, an African-American woman, crossed into the then mostly white, male arena of science fiction in the 1970s, demonstrating that women of color could successfully inhabit the worlds of science fiction.

At the same time, she refused to let either herself or her writing be solely defined by her race or her gender—though both affected her subject matter and overall themes. In this way, she also crossed into the mostly white, middle class arena of 1970s feminism.

Countless individuals have opened their horizon to writing thanks to Butler’s example. Beyond this, following her death in 2006, the Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship was established to enable writers of color to attend one of the Clarion writing workshops.

Clarion workshops are credited by many of today’s sci fi writers as central to their career advancement. In addition to attending Clarion, Butler taught at Clarion West here in Seattle, and gave generously to help others enter the field. To date, more than 20 writers have attended Clarion thanks to the Butler Memorial Scholarship.

On Becoming Dandelions: Scaling Positive Obsession

Inspired by Octavia Butler’s collective works, Adrienne Maree Brown’s book Emergent Strategy converts Butler’s fiction into a relationship-based approach for creation and change making. She writes:

Octavia Butler, one of the cornerstones of my awareness of emergent strategy, spoke of the fatal human flaw as a combination of hierarchy and intelligence. We are brilliant at survival, but brutal at it. We tend to slip out of togetherness the way we slip out of the womb, bloody and messy and surprised to be alone.

Brown argues that there are examples of Butler-style emergence everywhere: in birds flocking, in oak trees holding tight to one another in a storm, in the Black Lives Matter movement. My favorite of her examples was of the dandelion which grows boundlessly regardless of how the human world perceives it.

Dandelions don’t know whether they are a weed or brilliance. But each seed can create a field of dandelions. We are invited to be that prolific. And to return fertility to the soil around us.

These days, I think of the dandelion often, and try not to worry whether my writing is perceived as a weed. Not only do I enjoy writing more with this mindset, but I’m seeing improvements in my writing abilities with each subsequent story. Hopefully, one day, this obsession will earn my writing a place near Octavia Butler on bookshelves. But even if not, I will still fill this field with stories.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.