How to Respectfully Wear Cultural Ethnic Wear If You're Not from the Community?

A Guide to Honoring Traditions with Sensitivity and Style

South Asian traditional clothing, such as the sari, lehenga, salwar-kameez, kurta, and sherwani, has become increasingly visible in global fashion and travel contexts. This can be a form of cultural appreciation, but if done without understanding it may cross into cultural appropriation. Experts stress that wearing another culture’s dress with respect demands education, context, and credit.

For example, a University of Wisconsin scholar notes that certain South Asian styles “we have been shamed for or even outlawed” are suddenly “celebrated as chic or exotic when…worn by non-South Asians”.

In her view, “appreciating” South Asian dress is acceptable only if one learns its history and significance: “that appreciation…requires education, it requires context, and it requires respect. And you cannot just aesthetically borrow things without understanding the culture”.

Throughout this report, we outline the history and meaning of key garments, highlight insider perspectives (designers, community members, academics), and give detailed guidance on how outsiders can wear South Asian ethnic wear in a respectful way.

Traditional South Asian Ethnic Garments and Context

Sari (Women’s Draped Dress)

The sari (also spelled “saree”) is one of the most iconic South Asian garments. It is an unstitched long cloth, typically 5–9 yards, that is wrapped around the body in various regional styles.

As textile historian Rta Kapur Chishti observes, the sari “has filled the imagination of the subcontinent,” serving both as a daily dress and a symbol of feminine grace; its flowing drape can “conceal and reveal the personality of the person wearing it”. The word sari itself means “strip of cloth” in Sanskrit, and women in South Asia have been wearing sari-like drapes for millennia.

National Geographic notes that the first mention of a sari appears in the ancient Rig Veda (c.1500 BCE), and sculptural evidence from early Indian art (1st–6th centuries CE) depicts women in draped garments akin to saris.

Today saris are worn in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere; different regions have distinct draping styles (e.g. Bengali, Gujarati, Maharashtrian styles).

Sarees may be plain or richly decorated, and color choices can carry meaning (for example red saris are traditional bridal wear, while white is often reserved for mourning in Hindu cultures).

Notably, even the common practice of wearing a fitted blouse under the sari is a colonial-era innovation: British-era modesty norms once compelled Indian women to add a stitched blouse and petticoat to the ancient drape.

Lehenga/Choli (Women’s Skirt and Blouse)

The lehenga (also called a ghagra) is a long embroidered skirt worn by women, usually paired with a fitted blouse (choli) and a dupatta (long scarf). Its origins lie in ancient draped garments (the antariya and stanapatta of antiquity) that evolved into a stitched skirt around the waist.

By the Mughal period, elaborate lehenga-choli ensembles were courtly fashions for North Indian royalty. Today the lehenga-choli is a common outfit for brides and for festive occasions in many parts of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. It is often lavishly embellished with embroidery, mirrors or beads.

Because the lehenga historically signaled Mughal and Rajput royal heritage, outsiders should be especially careful not to treat a wedding lehenga as a mere costume or fashion piece; for example, wearing a red bridal lehenga in a casual or seductive way would likely be seen as insensitive.

Salwar-Kameez and Anarkali Suits (Women’s Tunic-and-Trousers)

Introduced to South Asia by Persian and Mughal influence, the salwar-kameez is a stitched ensemble of a long tunic (kameez) over loose trousers (salwar), often accompanied by a dupatta.

It became widespread in the Punjab region from the 13th century onward and is now a staple for women (and men) in northern India and Pakistan. Pakistan’s national dress, for instance, is the salwar-kameez for both genders.

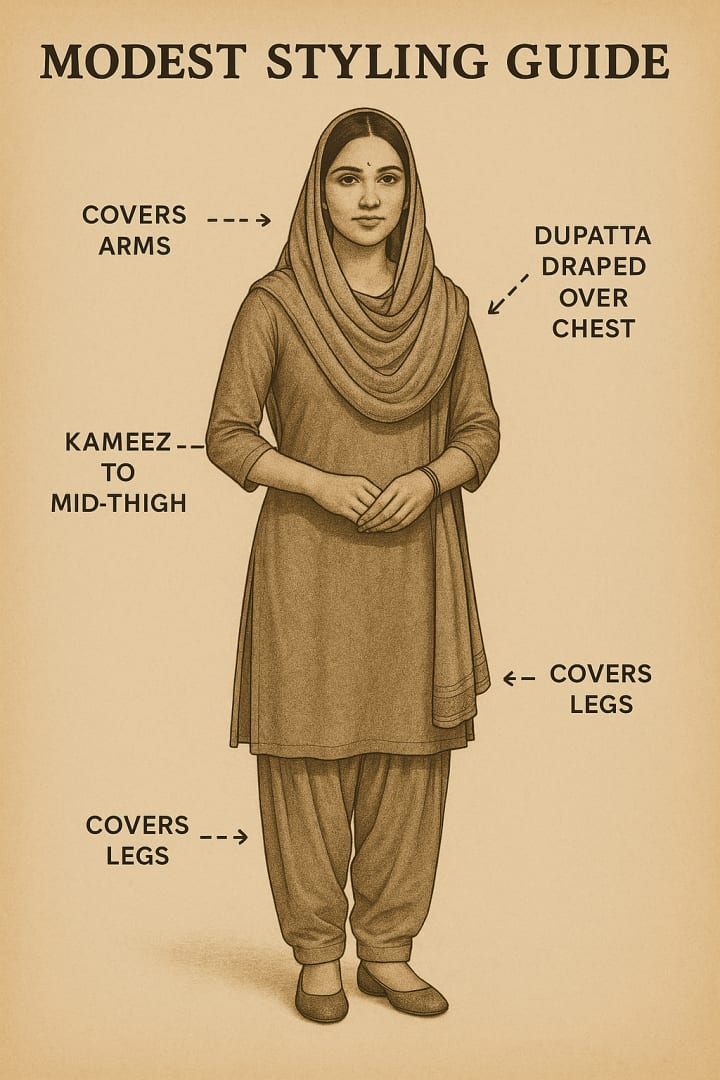

Anarkali suits, with floor-length, frock-style kurtas, are a South Asian variant that dates to the Mughal era (the name Anarkali comes from a legendary Mughal courtesan). These outfits are generally modest (the kameez may cover the body to mid-thigh or lower, and a dupatta can be used to cover the chest or head).

When worn by non-South Asians, a salwar-kameez or churidar suit is usually considered respectful if it is well-made, covers appropriately (see below), and is worn in an occasion-appropriate context (wedding, festival, etc.), rather than as a random exotic costume.

Kurta and Pajama (Men’s Tunic and Trousers)

The kurta is a loose collarless tunic for men (and sometimes women) that extends roughly to the knees, paired with pajama-style trousers or fitted churidar pants.

The kurta has deep roots in Central Asian tunics of the late ancient and medieval era. It evolved through Mughal times into everyday and formal wear for South Asian men. Kurtas can be made of cotton, silk or linen, and may be plain or decorated with embroidery.

For formal wear, men may also wear a Nehru jacket or achkan over the kurta. In most settings in South Asia today, a well-tailored kurta-pajama is an acceptable and even appreciated choice of dress for foreign men (e.g. at a wedding or festival), provided it is worn neatly and with modesty (see below).

Sherwani and Formal Men’s Wear

The sherwani is a long, fitted coat worn over a kurta, buttoned down the front, often made of silk or brocade with embroidery. It originated in the 19th century as a fusion of Mughal and Victorian styles: historians note it evolved from the Mughal angarkha (a Persian-influenced wrap coat) by adding European tailoring (buttons, mandarin collar).

Early on it was the dress of Muslim aristocracy during British India. Today a sherwani (often paired with a matching churidar pajama and turban) is a traditional wedding or formal outfit for men in India and Pakistan. Foreign guests at South Asian weddings sometimes rent or purchase a sherwani for the occasion.

When non-South Asian men wear sherwani-style coats at weddings, this is generally seen as respectful formality, but it should be done sincerely (e.g. properly fitted, not as a silly costume) and often with guidance (hosts or designers will typically assist).

Religious and Regional Variations

Certain garments have religious or regional significance. For example, Hindu priests may wear a dhoti (a wrapped lower garment) and bare-chest in rituals; many Sikhs wear turbans as a religious symbol.

Non-South Asians should not adopt these items as fashion: wearing a Sikh turban or Hindu priest’s shawl, for instance, would be seen as deeply inappropriate. Similarly, some communities use specific colors: white and black are traditionally funeral colors in Hindu and Sikh culture, so wearing white/black at a celebratory event can be jarring.

Regional variations are vast (South Indian pavadai, Pakistani shalwar-kameez, Nepalese gunyo-choli, etc.); a respectful visitor should either select mainstream outfits or, if wearing something region-specific, learn the local norms. When in doubt, it is wise to ask a local host what is appropriate.

Cultural Appropriation vs Appreciation in South Asian Dress

Conceptual Distinction

Many scholars define cultural appropriation in dress as the uncredited or disrespectful borrowing of a minority culture’s clothing by a dominant culture, especially when power imbalances exist.

FIT sociologist Jung-Whan Marc de Jong explains that cultural appropriation typically involves a dominant group adopting elements of a marginalized culture “without consent, recognition or financial compensation”.

By contrast, cultural appreciation is said to occur when another culture’s clothing is adopted with understanding, respect, and acknowledgment. As Mushtaq (UW–River Falls) put it: appreciating South Asian dress is fine, but it “really requires education, it requires context, and it requires respect”. Importantly, insiders note that intent matters but is not the only factor: even well-meaning adoption can offend if it overlooks the item’s meaning.

For instance, one Indian American commentator observes, “It’s okay to appreciate the culture of South Asia… but you cannot just aesthetically borrow things without understanding the culture and without understanding the context”.

Community and Designer Perspectives

South Asian insiders offer nuanced guidance. A Pakistani-American university columnist writes that “there are parts of my culture that make me uncomfortable when non-Desi people participate in them,” but she also acknowledges, “there are some parts of my culture I’m glad to share, given they are experienced in a respectful context”. Her advice: if someone from the culture expresses discomfort, listen to them.

Similarly, a 2023 interview with South Asian American youth quoted one young woman saying it is “really nice when people are wearing Indian clothing” but drawing a line at misusing sacred symbols (she cited Rihanna’s photo shoot wearing a Hindu deity pendant as unacceptable). These voices convey that many South Asians welcome outsiders wearing their ethnic dress as long as it’s done respectfully and in appropriate settings.

South Asian designers echo this. Fashion designer Anita Dongre (and colleagues) emphasize that any cultural borrowing must be accompanied by mindfulness and credit: “Like anything in life, respect is key,” says Dongre (Mohan), and wearing another culture’s traditional outfit “is a huge compliment to take inspiration from something, but at the end of the day it’s up to you to interpret it with integrity”.

Similarly, designer Dhruv Kapoor (Milan Fashion Week) notes that cultural mixing on the runway is inevitable and “we are all entitled to our opinion,” but cautions: “when we’re referring to a specific culture, all we need to ensure is that we’re doing it respectfully”.

Kelvin Goncalves, a New York boutique owner, likewise observes that most cultural borrowing “can be done” if done with “respecting the traditions… and acknowledging the inspiration”; but if one “claims it as yours without giving credit… you’ve definitely gone too far”.

In sum, insiders urge non-South Asians to learn and credit the origins of garments, to acknowledge the artists and communities behind them, and to wear the clothes with sincerity rather than as a cheap “costume.”

Social Media and Celebrity Influence

In recent years, social media and celebrities have amplified both positive and negative examples. On one hand, influencers and stars like Zendaya, Priyanka Chopra, and Selena Gomez have popularized saris and bindis in high-profile settings, often meeting with applause.

On the other hand, TikTok and Instagram have become platforms for critique. For example, in early 2025 dozens of South Asian content creators pointed out striking resemblances between Western fast-fashion designs and traditional South Asian garments.

Reformation’s 2025 spring collection (worn by model Devon Carlson) included a co-ord set of skirt, camisole and scarf that many noted was “unmistakably like a South Asian lehenga,” prompting online commenters to demand credit to South Asian fashion. Likewise, H&M and other brands have released kurta-like tunics over pants that South Asians say mirror the shalwar kameez.

These incidents revived debates over who profits when cultural dress is popularized: a Week magazine article reports that critics argued Western brands are “turning traditional attire into a tool to perpetuate fast fashion,” selling “our lehengas…as ‘fashionable’, only [with] the cultural significance…stripped away”.

At the same time, media coverage has pushed for better acknowledgment. The Washington Post highlights that South Asians “appreciate learning about garment history,” saying brands missed an educational opportunity by not explaining how designers like John Galliano were inspired by Indian dress.

Scholars stress that power imbalances matter: FIT professor de Jong comments that what makes appropriation different is that the adopting culture typically dominates or is wealthier than the source culture, profiting while ignoring the garment’s origins. South Asian social-media figures themselves express frustration.

For instance, YouTuber Maryam Siddiqui says, “Our culture means so much to us… the jewelry, the dresses… it’s just not a dress”, underscoring that ethnic clothing carries deep meaning beyond mere aesthetics.

The overall media narrative urges non-South Asians to proceed with humility: to be mindful of the history behind each garment, to credit inspirations, and to engage respectfully rather than treat the clothing as a superficial trend.

Respectful vs. Disrespectful Use (Illustrative Examples)

In practice, respectful wearing means treating the garment with sincerity and context. For instance, a foreign wedding guest who asks a bride or family how to drape a sari, and then wears it elegantly to the ceremony, is often warmly received.

As one travel blogger noted, Indian hosts and even airport officials have complimented her when she wore a properly-wrapped sari with modest blouse and dupatta. Similarly, non-South Asians who don salwar-kameez or kurta-pajamas at local festivals (with appropriate modesty) generally find their effort appreciated.

By contrast, disrespectful instances tend to involve stripping the garment of its meaning or wearing it in trivialized ways. Examples cited by South Asians include using religious symbols as mere accessories (e.g. Rihanna’s lingerie photo with a Ganesh pendant, which one young woman called “not OK” because “you can’t wear our gods in that situation”).

Likewise, when celebrities or advertisers have treated cultural dress as a costume, such as a Western singer in a sari-and-bindi for a pop video, or retailers marketing bindis as “fashion stickers” for Halloween, critics have called out these acts as appropriation.

In one high-profile case, actress Vanessa Hudgens was mocked on social media for wearing a red bindi (a decorative forehead dot), prompting writer Aarti Olivia to remark on the double standard: “When I wear the bindi… it makes me traditional, but if Vanessa Hudgens wears a bindi, it’s ‘cool?’”.

An online retailer (ASOS) even placed bindis under “Halloween accessories,” sparking swift consumer backlash and a product recall. These incidents illustrate that treating sacred or traditional items as cheap fashion, without credit or understanding, is widely seen as disrespectful.

Guidelines for Non-South Asian Wearers

In light of these cultural nuances, the following practical guidelines can help ensure respectful appreciation:

Seek Local Guidance. When possible, consult someone familiar with the culture. If you are attending a South Asian wedding or festival, ask your host or local friends about appropriate dress. Many South Asians appreciate curiosity: one student columnist observes that “our elders love seeing foreigners wearing South Asian attire,” as long as it is not done arrogantly.

Be prepared to have your outfit adjusted by a local tailor or helper (for example, many sari shops will let you try on a sari and give a small tip for draping help).

Listen if any insider expresses discomfort: as noted above, outsiders should “listen” if a South Asian person says your dress or style is inappropriate. In many temple or mosque visits, follow local protocols (remove shoes, cover head or shoulders as required). In sum, approach the garment as you would any cultural tradition, with deference and a willingness to learn.

Dress for the Occasion. Understand the context before choosing an outfit. At a Hindu or Sikh wedding, bright festive colors (reds, golds, greens) are customary; guests typically avoid white (the color of mourning) and black.

Women might wear a sari, lehenga, or anarkali suit; men may wear a kurta-pajama or suit (adding a silk scarf or shawl is a nice nod to traditional style). For Muslim celebrations like Eid, modest suits or salwar-kameez with a hijab for women are appropriate.

During religious ceremonies (Diwali puja, temple visit, church/mosque), modesty is key: cover the shoulders and knees, and use a dupatta or scarf to drape respectfully.

If attending a cultural festival or tourist event (e.g. Holi festival, cultural show), you can don South Asian dress in the spirit of participation, but still be modest, for example, wearing cotton clothing that you don’t mind getting colored or dusty.

When in doubt at any site, err on the side of modesty and ask permission if you’re unsure about certain garments (e.g. temple priests’ attire or ceremonial robes).

Modesty and Styling. South Asian norms of modesty tend to be more conservative than typical Western fashion. Women are expected to cover their chest (with a full blouse) and often their midriff, depending on the style of clothing.

If wearing a sari or anarkali dress, ensure the blouse is snug and the dupatta (long scarf) covers the décolletage or drapes over one shoulder.

At religious or formal events, women commonly cover their heads with the dupatta; this is not always required, but doing so can be a sign of respect in some communities.

Men should avoid very short sleeves or shorts in religious settings, a kurta-pajama naturally covers to the knee or lower, which is usually appropriate.

In general, choose clothing that is well-fitted (but not tight) and clean; for example, a neat kurta with churidar pants is preferable to a crumpled T-shirt and jeans if the event is semi-formal. Footwear should also respect the venue: temples often require removing shoes, and some mosques or gurudwaras expect sandals.

Accessories and Behavior. Traditional South Asian attire is often worn with specific jewelry and accessories (bangles, earrings, bindis, anklets, etc.). Non-South Asians may wear such jewelry if it complements the outfit, but should avoid religious symbols unless invited (e.g. do not wear a sacred tilak or Sikh kara unless you have cultural ties).

Applying mehndi (henna tattoo) to the hands or feet is generally fine and can be seen as appreciation (henna is widely admired). The bindi (forehead dot) can be worn stylistically, but one should understand that for many women it signifies marital status or religious tradition.

If choosing to wear a bindi, do so in good spirit (for instance, as a sign of祝福 at a wedding) and not as a fashion gimmick. Above all, carry yourself with respect for the garment: do not wear a sari or sherwani sloppily or in a mocking way.

Allow South Asians to see that you value their clothing, for example, compliment the craftsmanship, ask for help with draping with humility, and avoid any joking or stereotypical behavior (like pretending to speak broken Hindi) while wearing the outfit.

Sourcing Garments Ethically. Where and how you obtain the clothing can also reflect your respect. Supporting South Asian artisans and fair-trade platforms helps ensure that wearing these garments is not just a one-way benefit for outsiders.

Experts note that every traditional outfit has a labor history: today, much of South Asian textile production is done by underpaid workers. One report warns that factories in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan often produce export garments under dangerous conditions and low wages.

To counter this, favor handwoven or hand-embroidered items directly from reputable South Asian designers or cooperative artisan groups. For instance, a specialist retailer notes that buying directly from weavers or fair-trade collectives “sustains traditional Indian crafts,” creates rural livelihoods, and “ensures fair wages and ethical working conditions” for craftsmen.

In practical terms, this means shopping at trusted boutiques (often found in ethnic enclaves or online), paying artisans directly (if possible), or even renting garments from companies that work with local tailors. Avoid impulse purchases of cheap knock-offs or “festival costumes” that strip cultural meaning and do not benefit the creators.

In short, let the purchase itself be as conscientious as the wearing: by wearing South Asian dress in solidarity with its makers, you honor the whole tradition rather than just the label.

Final Word

Wearing South Asian ethnic attire as a non-South Asian can be a meaningful gesture of cultural appreciation, but it requires awareness and sensitivity. A respectful approach involves learning about each garment’s history and symbolism, listening to South Asian perspectives, and choosing appropriate circumstances and styling.

As several insiders emphasize, taking inspiration from another culture is a “huge compliment” if done with respect and integrity, but claiming it without credit or context crosses the line.

In the age of social media, even well-intentioned acts are scrutinized, so non-South Asians should embrace guidance from community members, give due credit in conversation (e.g. “I love your sari style, may I try one?”), and wear the clothes with genuine admiration rather than as a novelty.

When travelers ask questions, source authentically, and dress with modesty and courtesy, they are often received warmly. In this way, cross-cultural dress becomes a form of exchange and learning, aligning with the view that “fashion, if used in the right way, can be a great unifier”.

Ultimately, South Asian ethnic wear is not merely a costume, it carries centuries of artistry and tradition. By honoring that heritage through informed, ethical, and respectful choices, outsiders can truly pay tribute to South Asian culture rather than appropriate it.

Sources: Historical and cultural details drawn from scholarly and journalistic sources on South Asian dress nationalgeographic.com en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org. Perspectives on appropriation/appreciation are taken from interviews with South Asian designers, academics and community members tatlerasia.com vogue.in washingtonpost.com. Fashion industry incidents and debates are documented by media reports elle.com.au washingtonpost.com theweek.com.

About the Creator

Nawab Parker

With 40 years in the making, Nawab Parker has earned its place as a leading name in premium men’s ethnic fashion. Shop the latest men's ethnic wear trends at Nawab Parker. Discover kurta pajamas, sherwanis, Indo-western styles, and more...

Comments (1)

It's great that South Asian traditional clothing is getting more attention. But like you said, it's crucial to understand its history and significance before wearing it. I once saw someone wearing a sari without a clue about its meaning, and it just didn't sit right.