Julio Aguirre

Julio Aguirre, remarkable life journey, a highly accomplished and resilient long-distance runner. (Advice and Inspiration for Senior Runners)

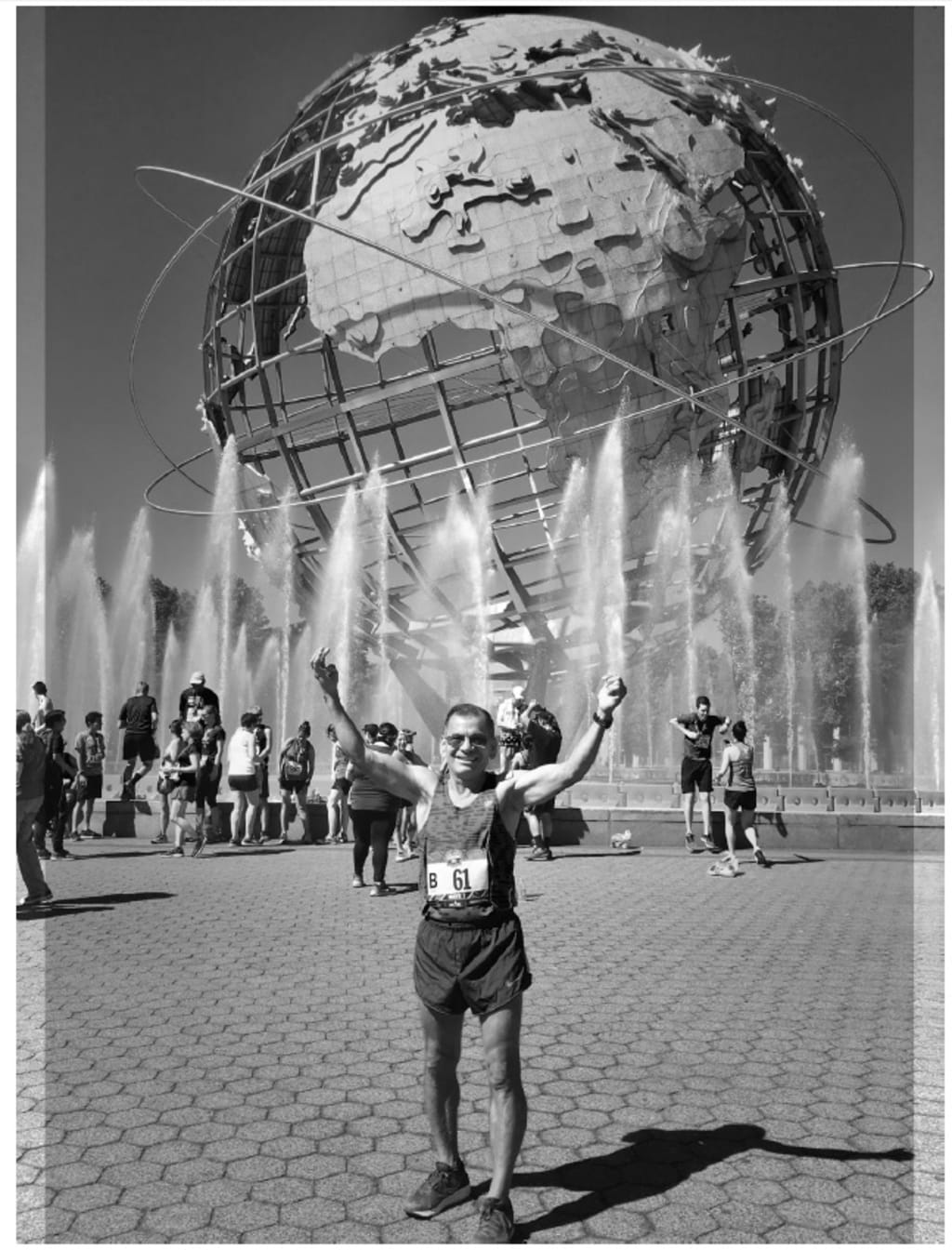

Julio Aguirre

DOB: June 16, 1946

Residence: Perth Amboy, New Jersey

Everyone adores Julio.

Julio Aguirre arrives for our interview dressed in a dark blue suit and tie, looking suave with a wicked sparkle in his eye, as if he's about to reveal a secret. He is quite charming. I knew this interview would be different than others, and I was in for a treat.

When I called him, he stated he'd rather meet in person because his English isn't that good and he enjoyed meeting people. I was familiar with his exceptional running career. Since he has thirteen times won his age division at the esteemed New York Road Runners (NYRR) Club Night, which recognizes the organization's top runners by age group. Until we sat down together, I was unaware of his backstory, even though I was aware of him and how enthusiastically the crowds support him at every event. I now have the highest regard for Aguirre, not only as a very talented runner who has completed 65 marathons, but also as a modest individual who has overcome great adversity in his life and is currently seventy-two years old and at the top of the world. One of six children.

Julio Aguirre was born in Ecuador in 1946. His family was impoverished and his father passed away when he was quite small. He says, "I was a street kid." "I made money for food by selling anything I could find on the street." He was destitute, but his mother insisted on sending him to school. Her suspicion was correct; education would be the means by which he would escape poverty. Aguirre discovered that he had the intelligence to excel academically and rank first in his class. His will to succeed and be the greatest would come in handy in the future.

He went on to teach arithmetic in high school. However, he fell in love with one of his students in a storyline straight out of a romance book; she was seventeen and he was twenty-five. To maintain their relationship, he left his work. She relocated to the US after graduating and made a vow to come back for him. She gave him $800 to come live with her in New York, but she never came back. He planned his admission into the US, flying to Mexico City first and then traveling to the US border in California, full of excitement at being reunited. Since Aguirre lacked a passport and documentation in 1977, he would have to enter the country illegally. He told the customs officer he was carrying $800 in cash as he breezed through the process in Mexico City, both anxious and happy. The events that transpired next are straight out of a thriller: when he was traveling in a taxi to the bus station to catch a bus to the border, two automobiles crashed into his taxi, and guys wearing masks and guns burst out, demanding money. Aguirre gave the money to the man, stunned and terrified, and was abandoned by the side of the road. He received assistance from onlookers at the incident and enough cash to cross the border.

I'm sitting here glued to my seat as Aguirre tells me this story. I find it hard to believe that this well-dressed man, who is adored by New York City runners and a national hero, has such an interesting life.

.. Using a "coyote," who was constantly on the lookout for border patrols, it took him two weeks to cross the border. He lost seventeen pounds traveling with little food or water. Upon reaching Tijuana, the coyote placed him in a car's trunk and drove him six hours to Los Angeles. All he could afford to eat was bananas while his girlfriend sent additional money for a four-day train trip from Los Angeles to New York City. But when his true love found him at Manhattan's Penn Station, it was all worthwhile. They got married two weeks later. His green card arrived three months later.

Despite his happiness in love, he was unable to speak any English and was forced to work menial jobs. He eventually lost his temper and started to feel lonely, longing his family in Ecuador. "I was sweeping floors and pushing carts around here, and I came from a professional background in my country," he claims. After thirteen years of attempting to provide for his three children while living in a Queens’s basement apartment, he felt as though there was no way out of the hole in his life. His days grew gloomier as he began to drink and smoke. After thirteen years, his wife moved the children back to Ecuador when their marriage collapsed.

"I had lost my identity," Aguirre claims. “I wanted to die because I was so miserable. He began spending every weekend drinking with his friends. He once went drinking in Central Park with several pals, and after a wild night, he passed asleep. He yells, "I woke up and saw all these people running." He reportedly saw a NYRR race pass him in Central Park when he woke up. It reminded him of the day he placed first in a 5K back in high school. Even though Aguirre is not religious, realizing that race that morning was a revelation. "I wanted to run, something stirred inside of me."

He remembers. He began running at Flushing Meadow Park the following day. He started out not getting very far because of his drinking and smoking, but he persisted every day, jogging a little bit farther each time. And he gradually stopped drinking and smoking. When he joined a 5K a year later, in 1992, at the age of 45, he raced 22:13, or 7:10 miles per mile, and finished thirteenth in his age group. He was overjoyed. He claims, "I was up for the challenge. I knew I had a lot of work to do to get to first place for my age." He completed a 10K at a speed of 6:56 three weeks later. He trained by himself and advanced through the ranks, winning his age group, with a steely determination. In his debut year, he competed in nineteen races. He was nominated for Runner of the Year in his age group three years following his debut 5K. That year, he didn't win, but he could taste it. He joined the West Side Runners because he believed he would run faster if he had a team and a coach. Both his life and his running began to blossom.

Sleek, fit, and employed as a janitor, he returned to Ecuador to see his family in 1994. He spent time with his own family, made apologies with his ex-wife and their children, and fell in love with a new woman. This time, she stayed behind and he returned to America. They were married two years after she showed up at his front door. She urged him to seek for citizenship, earn an English degree at Queens College, and purchase a car and driver's license so he could drive to his races. Cheering for him, she stood at the finish lines. "I was elated, feeling truly blessed," Aguirre beams. Gradually, he emerged as a running legend in New York.

Julio is now well-known to all. He became a racetrack icon for whatever reason—his charisma, his smile, his gregarious personality, or all of them put together. That undoubtedly had something to do with the fact that, even in extremely cold weather, he constantly dresses in a singlet and shorts. "It helps me run more quickly," he smiles.

Ten years ago, Aguirre was approached by Gary Muhrcke, the 1970 winner of the inaugural New York City Marathon, while he was receiving another NYRR Runner of the Year award. Muhrcke, the man behind the Super Runners Shop chain of running businesses, was inspired by his perseverance and offered him a position selling running shoes after learning about his life story. Aguirre approached his work with the same tenacity and devotion that he gives everything else in his life, and before long, he was the top salesman.

Be not misled into believing that Aguirre's endearing demeanor extends to the starting line. He competes aggressively. He acknowledges, "I can't sleep when I don't win." "I work harder after I'm beaten, so that person never beats me again." He occasionally sustains injuries from his demanding workout regimen. At fifty-three years old, he prepared for the Staten Island Half by doing the following during the week before the race:

Monday: 1:04 for 10 miles

Tuesday: 1:03 for 10 miles

Wednesday: 1:02 for 10 miles

Thursday: 1:11.01 for 10 miles

Friday and Saturday. Rest

Sunday: 1:19:43 for a half marathon PR

Aguirre admits, "I sometimes kill myself in my workouts, but I have to." "Someone is going to beat me if I'm not giving it my all."

Aguirre almost killed himself in 2002 when he was "killing himself" by running 400-meter intervals. He was really exhausted after the workout and found it difficult to go home. He passed out in the hallway as soon as he arrived. He was diagnosed with a heart attack at the hospital after his wife drove him there in a hurry. He had a stent put because clots in his leg had entered his heart. After fifteen days in the hospital, the physicians recommended that he give up running. He didn't. He sneaked out and jogged around the block a week after feeling well enough to return home. Maintaining this, he won his age group in a half marathon a few months later. He smiles and says, "I told my wife a little white lie." "Instead of running the race, I told her I was just going to watch it." Clots or no clots, I refuse to just watch my life pass me by. I don't believe his spouse was duped.

He is still troubled by the clots in his leg. Every time he races, according to his doctor, he is running a danger. His wife expresses concern for him and assures him he doesn't require any more medals to demonstrate his worth. The issue returned with a vengeance in 2013. His sprinting suffered as his physique grew larger. He took a two-year hiatus in order to manage them. "I detested those two years," Aguirre declares vehemently. "I ran a few twelve-minute test runs and questioned if I would ever be able to return." Yes, he did. At NYRR's Club Night in 2018, he was crowned Runner of the Year in his age group once more. He's vowed to avoid doctors. He is running races at a regular pace of 7:07 as of this writing.

How does he accomplish it? The first to admit that he doesn't do anything exceptional is Aguirre. He hardly drinks water, doesn't stretch, and doesn't follow any special diet. (He drank nothing during his first twenty-four marathons.) For what reason does he do it? He says, "Running saved my life." "God knows where I would have ended up if I hadn't seen the race in Central Park that morning, nearly thirty years ago. Most likely deceased. He acknowledges that he is a running addict. "If I haven't run, I can’t sleep." I would prefer to die if the day ever comes when I am unable to run.

Aguirre lives for running and eats and sleeps. He is able to click off statistics like learning the alphabet and race times. He has to reassess his objectives now that he is older and no longer pursues a personal best. "My goal is to improve upon my time from the previous year," he states. "It challenges me continuously."

Julio is well-known to all. He makes me think of the joke in the cult about Benny, the person who knows everyone. He wins a $1,000 wager from a friend one day that he doesn't know the pope. They then visit the Vatican. The companion of Benny is astonished when he suddenly finds himself standing with the pope on the balcony with a view of Vatican Square. He hears a man in the throng ask, "Who's the guy standing next to Benny?" and it gives him a double shock.

Aguirre tells me about a recent race expo where he waited in line to obtain an autograph from Bill Rodgers, one of his heroes whom he had never met, as like he is reading my mind about that joke. When there are only a few people left in front of him, a security guard approaches and informs him that Bill isn't signing any more autographs and that his time is over. Despite his disappointment, Aguirre acts like a gentleman and begins to walk away. That's when Bill glances up, recognizes him, and tells the guard, "Oh, that's Julio." He is welcome to remain.

In his seventies, Aguirre is aware of how fortunate he is to be running at this level. He remarks, "I do think I am starting to consider my age and try not to go beyond my ability." "Yet I do wish to succeed. I just know life as it is in my running.

It's not entirely accurate. Aguirre is not all that he seems. He writes and performs poetry, and he has read all of the classics. His children provide him great pride. One daughter is a teacher, and the other holds a PhD in English. His son is a real estate agent. His four-year-old granddaughter isn't far behind her eleven-year-old grandson, who is already winning races. He sheds tears when talking about his children. The president of Ecuador gave him the Ecuador Medal of Honor for International Sports Activity in 2014. His telling me all of this is not an act of arrogance or boasting. I can see the pride in his eyes, and it comes from the heart.

He had continued to speak the entire while we were speaking. He seems like a happy child who wants to share with you all the details of his incredible day and include you in it. However, he pauses, leans back, and takes a minute to respond when I ask him to summarize his life. "I'm not religious, but I do think that fate exists." Running entered my life for a purpose, and I must respect that.

Aged runners should not look up to Aguirre. He takes chances that could endanger his life or, worse, cause him to lose his running. He must prevail. He says, "The thought of running for pleasure is yet to cross my mind," in response to the question of whether he could ever reach a stage where he enjoys running only for the enjoyment of a simple outing. Right now in my life, consistency in victory is more important than winning any given time. The primary source of my inspiration is my winning attitude.

About the Creator

Nasir Nabil

Nasir Nabil: an economist and writer.

Comments (2)

Interesting

Well written