Stop Celebrating Your Series A: The Ponzi Scheme of Modern SaaS

How to Escape the “Exit Liquidity” Trap and Build a Customer-Funded Fortress

Open LinkedIn right now, and what do you see?

Founders holding oversized checks. Team photos with “We just raised $5M!” captions—an endless parade of vanity metrics masquerading as success. The startup world has been brainwashed into believing that fundraising is a milestone.

I used to be one of them.

Five years ago, I closed a seed round that valued my SaaS company at $8 million post-money. I felt like a god. I hired three “VP” level executives, moved into a brick-and-mortar office in SoMa, and spent six figures on user acquisition.

18 months later, we were dead.

We didn’t die because the product was bad. We died because the capital acted like a painkiller — it masked the symptoms of a terminal illness. We were bleeding cash on customers who didn’t actually love us, but the money in the bank made us feel healthy.

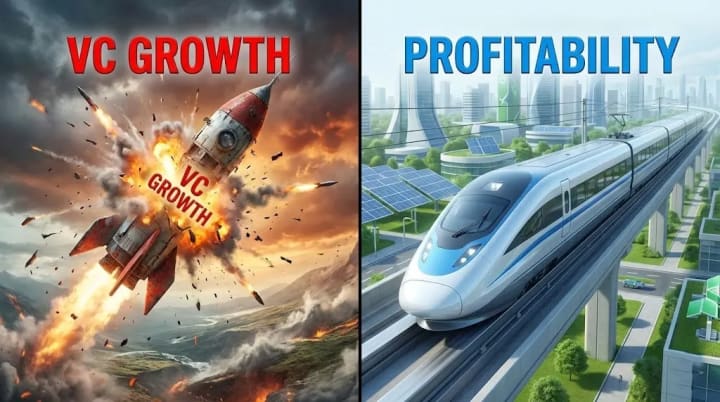

Raising venture capital is not a badge of honor. While high-risk capital has its place in the free market, in the SaaS world, it has mutated into a game of hot-potato passing.

It’s time to challenge the religion of “Blitzscaling.”

The Great IPO Pump and Dump

Let’s be clear: In a truly free market, Risk Capital plays a vital role. Investors betting on unproven, capital-intensive technologies — such as fusion reactors or space exploration — are essential to progress. They take massive risks for massive rewards. That is healthy.

But that is not what is happening in the software industry today.

The Venture Capital model has shifted from funding innovation to manufacturing “Exit Liquidity.”

Here is the playbook:

- VCs pour money into a startup to artificially inflate growth metrics (not profit).

- They hype the “story” to boost valuation in private rounds.

- They push for an IPO not to raise capital for the business, but to open a door for themselves.

By the time the company rings the opening bell, the goal isn’t sustainable value. The goal is to offload overpriced stock to public-market retail investors.

The IPO is no longer a beginning; it is the cash-out event for the insiders.

If you are a SaaS founder, you are the fuel for this machine. You are pressured to burn cash to create a growth narrative that looks good in a pitch deck, even if it destroys the long-term viability of your product.

“They don’t need your company to last 20 years. They just need it to look explosive enough to sell to the next guy.”

The Alternative: The “Sound Money” SaaS

If you are building hardware or biotech, you need their money. But if you are building Software as a Service (SaaS), you have zero excuse.

Cloud computing has driven the marginal cost of replication to near zero. You don’t need factories. You don’t need inventory.

This allows for a different path: The Customer-Funded SaaS.

This is a philosophical stance that values consumer sovereignty above all else. It is the belief that the only honest vote on your value proposition is a customer pulling out their credit card.

Here is the 3-step framework to build a Sound Money SaaS:

1. Sell Before You Code (The Validation Gap)

In software, the risk is not “Can we build it?” The risk is “Will anyone buy it?”

Engineers love to build. But writing code before getting a commitment is a form of vanity.

- The Action: Create a high-fidelity landing page or a clickable Figma prototype. Pitch it to 50 prospects.

- The Rule: If you cannot get a deposit or a signed Letter of Intent (LOI) on a promise, your value proposition is weak. No amount of VC money will fix a product nobody wants.

2. Day 1 Profitability (SaaS Only)

Since your marginal cost of goods sold (COGS) is virtually zero, your unit economics must be positive immediately.

The “Amazon Strategy” of losing money for 20 years does not apply to your B2B CRM tool. When you sell a subscription for $50/month, it shouldn’t cost you $300 in ads to acquire that customer unless your retention is ironclad.

- The Discipline: If (CAC + Servicing Costs) > LTV, you don't have a business; you have a charity subsidized by investors. Stop scaling the losses.

3. Low Time Preference

This is the core of sound economic thinking. Low time preference means delaying immediate gratification for long-term compounding.

VC-backed SaaS founders have high time preference — they need to hit 3x growth this year to unlock the next tranche of funding. This forces short-term hacks, spammy marketing, and churning customers.

A Sound Money founder builds for the next decade.

- The Result: You build features that actually solve problems, not features that look cool in a press release.

Real World Case: Look at Basecamp. Jason Fried and DHH have famously rejected the VC treadmill. They kept their team small, focused on profitability from the start, and ignored the “growth at all costs” mantra. While their competitors burned out or were acquired and shut down, Basecamp remains a profitable fortress.

“But I Need a Moat!”

I know the objection. “If I don’t raise $10M, a competitor will copy my software and outspend me.”

This is the great lie of the software industry.

Capital is not a moat. In SaaS, trust is the moat. Switching costs are the moat. Data integration is the moat.

When you take the VC path, you are forced to compete on their terms — burning cash. When you bootstrap, you compete on your terms — customer intimacy and product obsession.

- Mailchimp dominated email marketing for years without primary funding.

- Atlassian grew into a giant primarily through cash flow, not cash burn.

The Freedom of Profit

When you rely on VC money, you are essentially an employee of a financial instrument designed to extract value for Limited Partners.

When you are profitable, you are free.

You can say no to features you hate. You can ignore the hype cycle. You can build a product that aligns with your values.

Stop looking for a savior with a checkbook. In the world of SaaS, the market is the ultimate judge, and the market rewards value, not valuation.

“Revenue is vanity, profit is sanity, but cash flow is reality.”

About the Creator

Cher Che

New media writer with 10 years in advertising, exploring how we see and make sense of the world. What we look at matters, but how we look matters more.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.