AI at the Intersection of IP and Personal Branding:

New Frontiers in Branding Law

Entering 2026, generative AI remains the most significant area of IP and Branding Law, with a particular emphasis on personal branding. As set forth for the first time in Branding Law: Cases and Materials, there was a long-standing dichotomy between intellectual property law for the enforcement of corporate branding interests and the economic and dignitary interest torts of defamation and right of publicity for personal branding.1 However, with the growing interest in federal trademark registration by celebrities, our original delineation has become less clearly defined over the past several years. And as we’ll soon see below, generative AI is now sparking a further evolution, or even a revolution, in personal brand protection.

A. Bette Midler and Vanna White: Expanding the Traditional Paradigm

Based on right of publicity statutes currently adopted in twenty-seven states, plus common law recognition in over eight others for a total of almost forty in all, celebrities could file suit as an intentional tort for the misappropriation of name and likeness whether direct or implied with such rights often descendable after death.2 Currently, the No Fakes Act is making its way through Congress to provide federal right of publicity protections to combat generative AI misuse. If approved in its current form, rights holders will be granted a total of one’s lifetime, plus seventy years following an individual’s death to authorize use of voice or visual likeness within a digital replica.

On the state level, however, and particularly relevant to generative AI, right of publicity has even been extended to look-alikes and sound-alikes. Midler v. Ford Motor Company3 was a seminal decision in support of the latter. Holding that the defendant could not make use of a vocal soundtrack featuring the plaintiff's distinctive singing style as imitated by someone else, despite the defendant having properly licensed the copyright to Midler’s recording, this ruling vastly broadened personal brand protection and essentially outlawed implied celebrity endorsement without authorization, at least under California law. As later affirmed in Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc.,4 while California right of publicity law explicitly barred misappropriation of name, likeness and even voice, none of these were at issue here since it was not Midler singing on the defendant’s commercial, thereby expanding the scope of right of publicity judicially.

And as the Midler court concluded:

Why did the defendants ask Midler to sing if her voice was not of value to them? Why did they studiously acquire the services of a sound-alike and instruct her to imitate Midler if Midler's voice was not of value to them? What they sought was an attribute of Midler's identity. Its value was what the market would have paid for Midler to have sung the commercial in person.

A voice is more distinctive and more personal than the automobile accouterments protected in Motschenbacher. A voice is as distinctive and personal as a face. The human voice is one of the most palpable ways identity is manifested. We are all aware that a friend is at once known by a few words on the phone. At a philosophical level it has been observed that with the sound of a voice, "the other stands before me." D. Ihde, Listening and Voice 77 (1976). A fortiori, these observations hold true of singing, especially singing by a singer of renown. The singer manifests herself in the song. To impersonate her voice is to pirate her identity. See W. Keeton, D. Dobbs, R. Keeton, D. Owen, Prosser & Keeton on Torts 852 (5th ed. 1984).5

Likewise it was the same court just a few years later that extended right of publicity protection to celebrity look-alikes in White v. Samsung.6 Here, the defendant had released an advertisement humorously depicting a robotic version of the famed Wheel of Fortune co-host and letter-turner. Even though Vanna White’s human likeness was not being misappropriated, the defendant’s creative adaptation was at issue and considered similar enough to raise an actionable right of publicity claim to protect the plaintiff’s commercial identity from impersonation. Finally, in the landmark Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc. decision, personal brand protection was expanded to include catch phrases. So even with no direct reference to the plaintiff’s name or likeness, use of “Here’s Johnny” alone was enough to establish misappropriation of identity.7

B. Personal Branding in the Age of Sound-Alikes and Generative AI

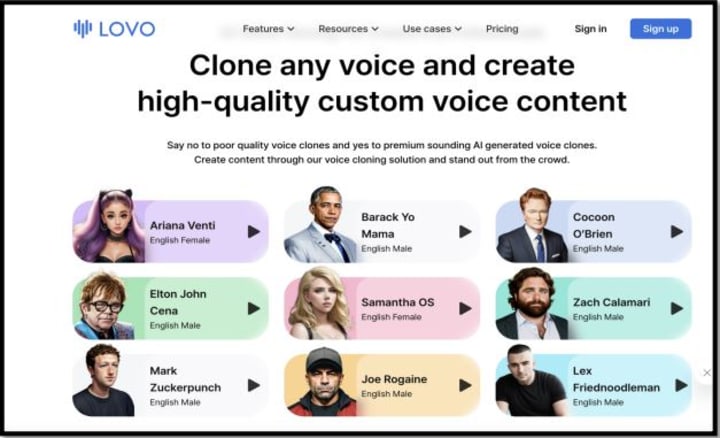

Under Midler, plaintiffs may have a strong cause of action against generative AI companies that are profiting from celebrity voice cloning models without prior authorization.. Just last year in Lehrman v. Lovo, Inc.8 this premise was tested against a defendant that was offering its subscribers text to speech voice generation for commercial applications, featuring unlicensed famous voices, brazenly-identified as “Ariana Venti”, “Joe Rogaine” and “Barack Yo Mama”, among others.

Unlike most generative AI lawsuits primarily alleging copyright infringement, this one featured state right of publicity claims and false association under the Lanham Act with the main copyright claims actually being dismissed as the AI-generated voices were deemed simulations rather than direct copies. As of this writing, the plaintiffs have amended their complaint as instructed by the court and motions are currently pending in advance of another trial, expected next year. However, what makes this case particularly distinct from Midler and White is that it’s being decided under New York state law.

While the defendant in Midler had actually hired someone with a similar singing style, now misappropriation of personal branding assets becomes much easier and more widespread through generative AI as the right of publicity claim here is based on unauthorized use of the plaintiffs’ actual voices, arguably being imitated through the defendant’s voice cloning models, rather than by another person. Rather than compensating entertainers for their endorsements, subject to prior approval and alignment with core values, marketers can circumvent the same through the use of generative AI, depriving celebrities of valuable revenue streams, while also potentially tarnishing or blurring personal brands.

Although a “voice” is widely-considered a figurative concept in the realm of corporate branding, speaking to what certain goods/services stand for in the consumer’s mind and forging a distinct emotional connection, it also applies literally in the area of personal branding. As such, it’s the individual’s actual voice that creates this special bond, while similarly serving as a source identifier.

As noted in Branding Law: Cases and Materials:

While privacy rights are widely-considered innate, publicity rights are acquired over time as a byproduct of fame and celebrity. In other words, publicity rights are also monetization rights. So while obtaining publicity often does not cost anything, protecting one’s right to publicity requires vigilance and sometimes lawsuits.9

One significant limitation as set forth in this decision, however, is how the various voices at issue were considered the product itself rather than a source identifier, despite the plaintiffs asserting false association under the Lanham Act in order to extend federal rights to their personal brands. Hence, the plaintiffs’ voices were not considered “marks” eligible for protection. Not to mention, there are certain limitations to right of publicity, including the commercial value and pecuniary interest requirements, whether actual or potential.

C. Matthew McConaughey and Sensory Trademarks: Revolutionizing Personal Brand Protection

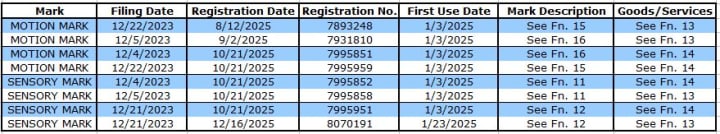

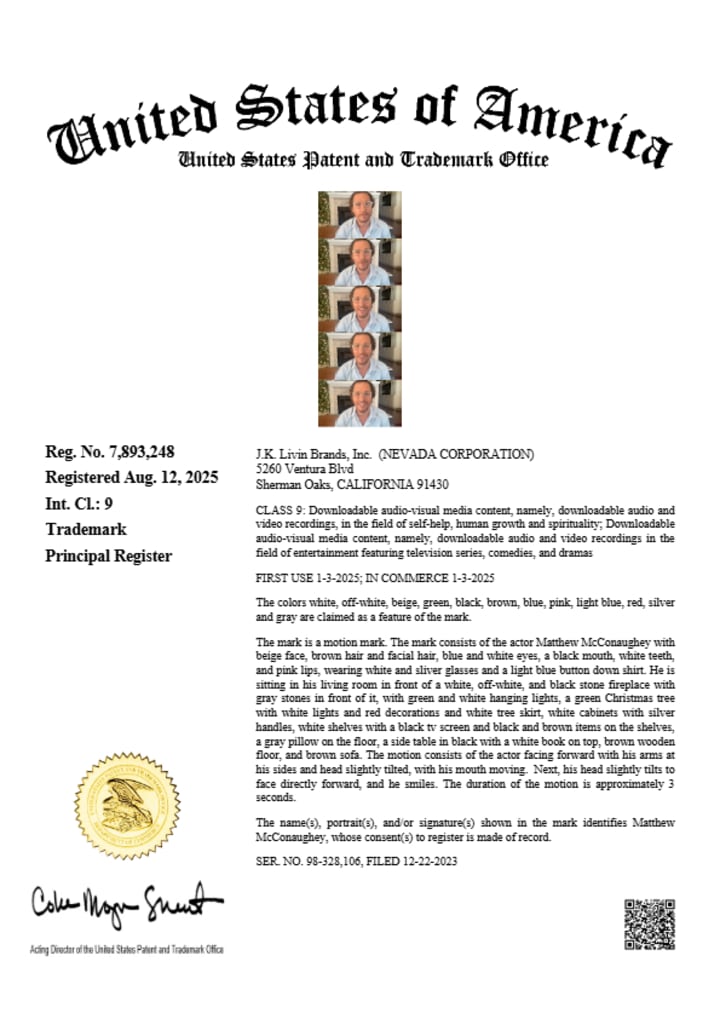

Anticipating these inherent limitations in right of publicity law relative to generative AI and the fundamental risks associated therewith, the original Lincoln Lawyer tried a completely different approach, having eight separate trademark applications filed on his behalf. And as of just last month, all of them have now been approved. What makes these particularly unique and quite important to future enforcement efforts is that we now see federal trademark law directly connected to personal branding, beyond merely applying for registration of one’s name or attempting to apply false association and unfair competition claims under the Lanham Act.

Capitalizing on last year’s AI strategic plan undertaken by the USPTO to loosen restrictions on sound and motion marks10, but since withdrawn for revision, McConaughey’s legal team successfully obtained registrations on various catch phrases, vocal cadences, and unique physical traits, essentially creating a trademark portfolio for the actor’s personal brand through both sound marks and motion marks, based on a series of short videos submitted to the Trademark Office.

Upon further analysis, four registrations are sensory marks with two representing a longer phrase11 and the other two featuring the actor’s signature catch phrase.12 Of these, one of each covers downloadable audio-visual content13 in International Class 009 with the other two identifying various entertainment services14 in International Class 041. Meanwhile, the final four registrations are motion marks with two representing an informal three second indoor video clip of the actor15 and the other two featuring a similar seven second outdoor video clip.16 Of these, they cover the same goods/services, respectively, and represent a broad protection strategy, overall.

Based on a thorough review of each application’s file history, all were initially refused due to various specimen deficiencies that were later corrected. Meanwhile the final registration, granted just last month, faced likelihood of confusion and non-distinctive sound challenges, both of which were successfully overcome. Curiously, 1/3/25 and 1/23/25 were claimed as priority dates even though first use likely occurred much earlier. And it’s surprising that only four marks are being applied for over two separate classes rather than adopting an even more comprehensive approach.

Theoretically, this strategy makes perfect sense as source indicators for products, such as brand names and logos, are commonly protected through trademark law for corporate branding interests. So it stands to reason that personal brand owners should be able to protect elements of their commercial identity, namely, voice and physical traits through trademark as well. However, as noted above, there is likely an element of notoriety needed to overcome a potential refusal based on non-distinctiveness. So this approach may be limited to those who have achieved at least a threshold level of fame to have acquired secondary meaning. Hence, in such instances it should provide a major deterrent against unauthorized AI-generated look-alikes and sound-likes, particularly as more celebrities begin doing the same for their own personas.

Furthermore, it will serve as a proactive tool in providing federal remedies should enforcement be needed, allowing plaintiffs to sue in federal court, while potentially entitling them to treble damages and attorney’s fees. Federal trademark registration for such sound and motion marks could also facilitate licensing opportunities for synthetic versions of celebrity voices, providing a valuable additional revenue stream for these entertainers. And unlike right of publicity, with trademark protection, plaintiffs will no longer need to establish commercial value and loss of pecuniary interest as likelihood of confusion provides a less rigorous standard. As such, rights holders could simply submit takedown notices to various online service providers, based on these federal trademark registrations, instead of litigating a costly right of publicity action and no longer needing to rely solely on Midler, White, Carson, et al.

Finally, celebrities could essentially live forever through lifelike recreations made possible by generative AI use of voice and image, along with 3D hologram technology. Under current right of publicity law there are wide variations from state to state as violations could potentially occur in some but not others. For instance, some states specifically include voice while others only protect name and likeness.17 Federal protection would ensure greater uniformity and predictability in regard to the above. Not to mention, many states still don’t recognize post-mortem rights at all, while there’s a wide variance in others, ranging from just forty years in NY to seventy years in CA, and as many as one hundred years under IN law.18 However, federal trademark law provides rights indefinitely as long as the mark is still in use and either registered to an entity from the beginning or assigned from the individual owner prior to death.

Given the potential wide-ranging effects on IP and Branding Law in particular, this protection strategy is certainly something worth following throughout the current year and beyond. So we’ll soon see whether federal trademark registration is truly an effective barrier against generative AI misappropriation, particularly if it’s eventually tested in court.

__________________

1 William Scott Goldman, Branding Law: Cases and Materials (2d ed. 2020).

2 See https://rightofpublicity.com/statutes.

3 Midler v. Ford Motor Company, 849 F.2d 460 (9th Cir. 1988).

4 Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc., 978 F.2d 1093 (9th Cir. 1992).

5 Supra note 3 at 463.

6 White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc., 971 F.2d 1395 (9th Cir. 1992).

7 Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc., 698 F.2d 831 (6th Cir. 1983).

8 Lehrman v. Lovo, 790 F. Supp. 3d 348 (S.D.N.Y. 2025).

9 Supra note 1 at 1174.

10 “Finally, the USPTO will analyze AI’s implications for trademark and associated unfair competition law and policy, assessing whether current laws sufficiently address the unauthorized AI-generated content that replicates existing proprietary content or mimics individuals’ names, images, voices, likenesses, and other indicia of identity (Name, Image, and Likeness, or NIL).” Artificial Intelligence Strategy, USPTO (Jan., 2025).

11 Trademark description - Sensory Mark: The mark is a sound. The mark consists of a man saying “JUST KEEP LIVIN’, RIGHT?” followed by a pause, “I MEAN” followed by another pause, and ending with “WHAT ELSE ARE WE GONNA DO?”

12 Trademark description - Sensory Mark: The mark is a sound. The mark consists of a man saying “ALRIGHT ALRIGHT ALRIGHT”, wherein the first syllable of the first two words is at a lower pitch than the second syllable, and the first syllable of the last word is at a higher pitch than the second syllable.

13 Claimed recitation of goods per trademark registration: Downloadable audio-visual media content, namely, downloadable audio and video recordings in the field of self-help, human growth and spirituality; Downloadable audio-visual media content, namely, downloadable audio and video recordings in the field of entertainment featuring television series, comedies, and dramas.

14 Claimed recitation of services per trademark registration: Entertainment services, namely, personal appearances by an actor and celebrity; entertainment services, namely, acting services in the nature of live performances and personal appearances by an actor and celebrity; entertainment services, namely, acting services in the nature of live visual and audio performances by a professional entertainer; entertainment services, namely, film and television show production service.

15 Trademark description - Motion Mark: The mark is a motion mark. The mark consists of the actor Matthew McConaughey with beige face, brown hair and facial hair, blue and white eyes, a black mouth, white teeth, and pink lips, wearing white and sliver [sic] glasses and a light blue button down shirt. He is sitting in his living room in front of a white, off-white, and black stone fireplace with gray stones in front of it, with green and white hanging lights, a green Christmas tree with white lights and red decorations and white tree skirt, white cabinets with silver handles, white shelves with a black tv screen and black and brown items on the shelves, a gray pillow on the floor, a side table in black with a white book on top, brown wooden floor, and brown sofa. The motion consists of the actor facing forward with his arms at his sides and head slightly tilted, with his mouth moving. Next, his head slightly tilts to face directly forward, and he smiles. The duration of the motion is approximately 3 seconds.

16 Trademark description - Motion Mark: The mark is a motion mark. The mark consists of the actor Matthew McConaughey with beige face and hands, brown hair and facial hair, white teeth, and black eyelashes, wearing a white button down shirt, silver necklace, silver watch, and silver rings. He is standing outdoors on a porch with brown wooden slats and a silver metal fence, with green trees and bushes, tan sand, white clouds, blue sea, and blue sky in the background. The motion consists of the actor standing and facing forward with his arms raised and palms open. Next, his arms open further wider. Then he glances to the side and places one hand on his hip and lowers the other hand out of the frame, with his body positioned at an angle, and turns his face forward. The duration of the motion is approximately 7 seconds.

17 See supra note 2.

18 Id.

About the Creator

WILLIAM SCOTT GOLDMAN

Senior IP counsel/founder of Goldman Law Group; ranked #5 in the world with 8,000 USPTO filings for creative clients in all 50 states and internationally; thought leader/author of "Branding Law Cases and Materials". Representing Innovation.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.