Communism, an ideology born in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, supported in its various forms a project of radical transformation of society. As a result, communist parties and regimes necessarily had an effect on gender relations, involving women and men (by juxtaposing images of man and woman) in a way that challenged - and simultaneously reproduced - existing roles.

Following Karl Marx (1818-1883), Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) did not see gender as having a specific order, hierarchy, or domination: men and women were considered neutral subjects. Male domination was reduced to a variant of economic domination, which was doomed to disappear after the revolution (Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, 1884). This belief was expressed in the activist practices of political parties, as well as in certain policies of communist regimes, especially in the beginning. These regimes provided constant support for women's suffrage, such as the French Communist Party, which fielded female candidates in the 1930s, at a time when women could neither run nor vote. They also established or confirmed the right of women to vote and run for office on their rise to power, beginning with the Russian Revolution of 1917. Communist parties were therefore among the most feminized in Europe, while some of the their activists rose to positions of responsibility, such as Germany's Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), Spain's Dolores Ibárruri (1895-1989) and France's Jeannette Vermeersch (1910-2001), all three elected to their respective parliaments.

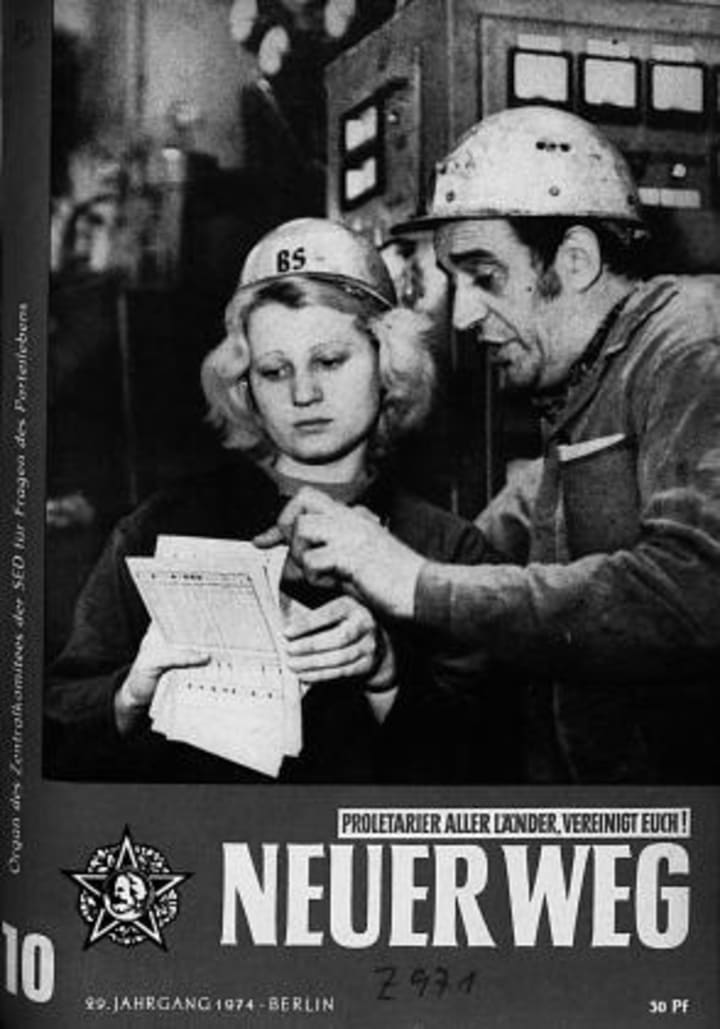

Combining economic and ideological considerations, communist regimes also massively encouraged paid employment of women and spread new representations, including those of the worker, tractor driver, and later engineer. With the Bolsheviks of the 1920s and sometimes the Communists in power in Central Europe in the 1950s, women's paid work went hand in hand with the management of the domestic work community, including childcare and education, which eventually had to be done. leads to the end. of traditional family roles and, according to Engels, "the decline of the family as an economic unit."

Communist regimes and parties, however, acted as if the roles they allowed women to assume were neutral, without exploring their androcentric dimension, hence the limits of emancipatory policies, and the resurgence of gender differences and hierarchies in communist parties. and in the societies they dominated. In parties, the proportion of women in positions of responsibility decreased as the level of the hierarchy increased, which was true in both the East and the West. In the GDR and Romania, the share of women in the party was 36% in the late 1980s, but was lower in the Central Committee (12% in the GDR, never reaching the desired 25% in Romania). As women, they were activists in mass organizations of a pacifist, charitable, cultural or local nature, rather than in the party itself. At national level, they have fulfilled their responsibilities in the fields of social affairs and education, which by their nature were considered to be feminine and therefore legitimate.

Moreover, the entry of women into the workforce has met with strong resistance within companies and has been selective in favoring sectors that had long been feminized (light industry, sales, administration, agriculture, education), namely those affected by mass unemployment after 1989.

This reproduction of traditional gender relations was joined by the failure of communist regimes to implement a genuine management of domestic tasks by the community, in addition to the opening of canteens for employees, nurseries and kindergartens, which were spread late and unequally, women are German being the best. The time spent on domestic work in the USSR remained unequally divided between the sexes when both worked (27 hours per week for women, 10 hours for men in 1970). In the absence of a real evolution of household roles, this failure, which was never offset by the unlikely arrival of a socialist consumer society, caused the daily dysfunction of the planned economies to fall on women.

Not only have communist regimes and parties failed to go beyond gender categories, but they have sometimes reaffirmed them, depending on the circumstances. This movement was first seen in the USSR, where the rise of "socialism" in the 1930s called into question the legislation of the 1920s, with the tightening of the law on divorce, the cessation of access to contraception and abortion, the dissolution of the zhenodtel. (The "women's section" of the Central Committee specifically on women's issues) and the renewed value given to the nuclear family in a pronatalist perspective.

The official discourse, conveyed through considerable iconography, dramatized men in roles such as workers, soldiers (to which partisans joined after 1945) and managers, while women personified mothers (often associated with the representation of peace after World War II). World) and peasants. This female figure very surprisingly replaced that of the bearded mujik in the 1920s. Some activists used these representations for political purposes: during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Dolores Ibárruri emphasized her role as a mother. while during the repression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Júlia Rajk (1914-1981) did the same in her role as widow of Interior Minister Laslo Rajk (1909-1949), who was executed on the orders of the secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party, Mátyás Rákosi (1892-1971).

The conservative sexual morality of the Stalinist period has gradually eroded since the 1960s (although Romania pursued a pronatalist policy, banning abortion, among other things), in line with ongoing developments in the West. This development took place in parallel with the increase in the level of education and the increase in women's employment, Poland after 1956 being a particular case, suffering a real traditionalist reaction that combined nationalism and hostility towards women's work. However, pronatalist concerns remained, as in Eastern countries there was a trend during maternal policies in the 1970s (eg Muttipolitik in East Germany) that made up for the lack of places in nurseries with generous parental leave.

Communist parties and regimes thus strove to liberate women, but without confronting the issue of gender relations. Therefore, it was difficult for them to politically defend specific women's interests or even propose a gender analysis without contesting the overall communist project, hence the difficult 1970s relations between feminist movements and communist parties in the West and their common opposition to of regimes. In the east. Communist regimes, however, allowed a less visible but widespread feminism to flourish, led by women in a variety of institutions - from works councils to the WIDF (International Federation of Democratic Women) - where they used their agencies to defends specifically feminine claims. In this sense, one could speak of feminists without feminism.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.