What Singing Feels Like

Things Between a Mother and her Baby

Sophie wouldn’t stop crying. Her sobs periodically tightened to a dissatisfied screech, and I gave up scrambling in the diaperbag to lift her with her blanket out of the carseat, pivoting in my squat on very non-sensible shoes. She flailed her chubby arms in slow, jerky, underwater circles as I rose and eased down in the booth again. One arm lightly bounced her and held her against my belly. The table edge left little room and she tore and smeared my sweater. I hated that I was worrying about my sweater again. The other hand fiddled the blanket over my shoulders, adjusting for the friction’s catch, until my lap and its squirming noise were properly pavilioned, and then felt for the buttons. They had been a little taut anyway. I could hear Sophie still upset, and she wouldn’t take. There, Sophie, what do you need? I caressed her head under the blanket as she twisted it this way and that. The cafe still echoed with her screams. I sighed. Glancing to the left I caught the eye of a woman across me from before we both turned away. Her look of impatience hung in my mind. I glared for a second at the paper cup on the table in front of me, froth still visible through the lipstick-stained lid.

Waiting at the bar two women six feet apart from each other looked at each other, and then met eyes over masks with a bemused momentary sisterhood. A young man in a soft scarf closed his laptop and left. Just left. I lowered the covering to look at Sophie, into the squinch of her eyes, questioning. She looked back in all the confusion of the recently born. I didn't want this, mama. I don't even know what's happening. I took a deep sigh, deeper than I thought I could, and gathered myself up, again, then gathered our things up, again, to settle her somewhere more soundproof.

Sophie's crying changed pitch, like a creek leveling out, when she saw me start to bustle, and then shrunk to whimpers when I finally began to straighten her in her carseat and stroke her warm, thin hair. The cafe sensed my imminent departure and eagerly anticipated the coming calm. As we rose to leave, I noticed that it was a mirror across from where I tried to set up camp. I equipped my mask, hoisted the bag over my shoulder like an artillerist, hefted the carseat in the crook of my arm, and waddled to the door. I could feel glances on me. The challenge of the pressbar was approaching - then the scum of salt and snowmelt, the parking lot's long tundra, and the puzzlebox of cardoors, which I had all navigated only eight minutes ago.

"Here, let me get that for you."

I could have wept. Do we absolve her, Sophie? "Thanks."

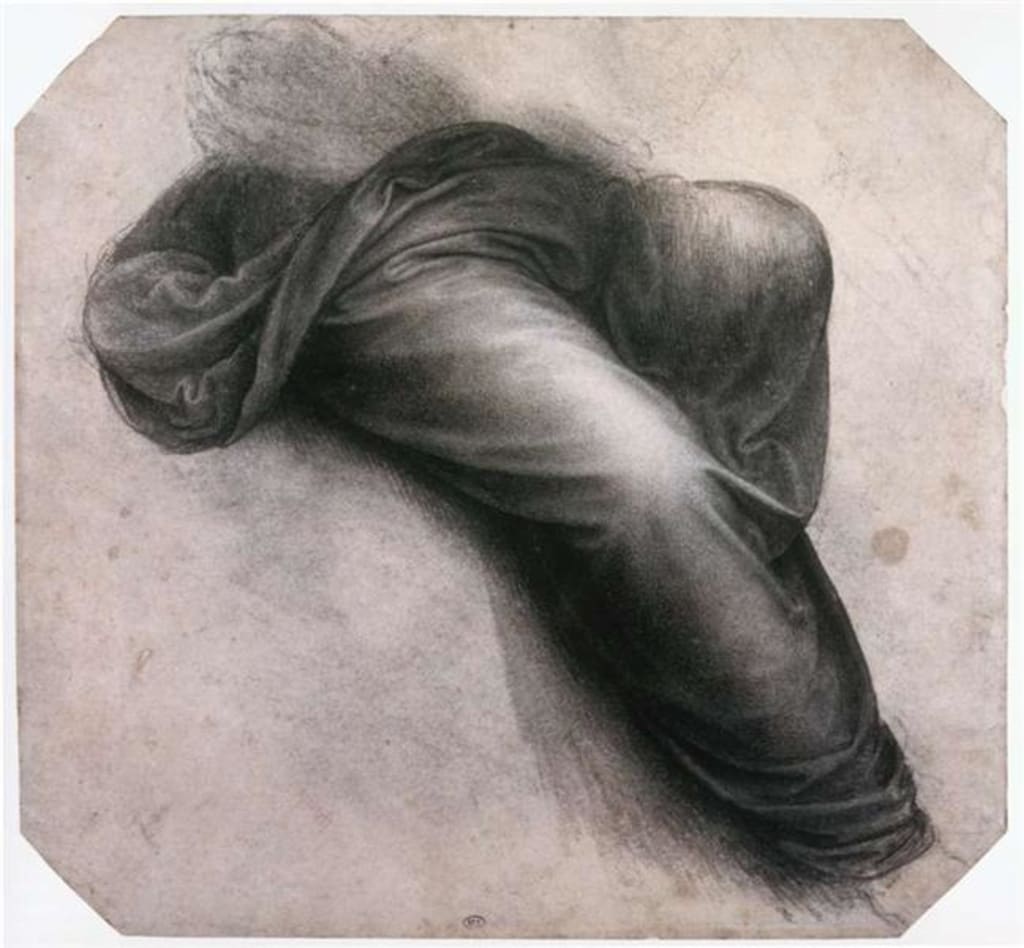

With a sincere gaze from behind curled balayage and a cute fern-patterned fabric mask, she stood to the side with her hand pressing the door open as wide as it went. Her wrist bent beautifully, and a bracelet dangled from its arc. I tried to squeeze through the door, too young to wear the word "matronly."

"Thanks," I said again out on the sidewalk. The other woman kindly crinkled her eyes - what did she want to say? - then turned to go back to her quiet seat in the now quiet cafe.

Sophie was already gurbling between sniffs, glad it was just her and her mama again. I walked with a lopsided swagger to keep the carseat from swinging. Glad you're feeling better, Soph. Between grunts I debated with myself if this counted as a workout. I had to take a rest near the shopping cart dock before the next set.

"Ma'am!" I heard someone call over the parking lot's slush. "Ma'am!" It was closer, and I turned. The woman from the door. I was ma'am.

"Excuse me, ma'am. I think you left this?"

My latte. I almost broke down again. "Thank you." I grabbed the cup. It already felt only warm.

"And your journal." She held out a thin black book, its pages clasped by a stretchy black band. It looked new.

I looked at it for a moment, as she looked at me. Did she mean it as a gift? Was it an honest mistake? I was actually flattered that she thought I had brought the notebook to a cafe, as if I were the sort to collect precious thoughts and story them into something worth sharing. Switching the coffee to my carseat hand, I plucked the book from her extended arm, as if I might discover it were mine, or maybe just to live a few seconds more in the fantasy. I wouldn't manage with all this weight to look inside the covers gracefully. Sophie, I promised you would have an honest mother.

"I'm sorry," I admitted, examining the book from the outside, "I don't think it's mine."

The woman's eyebrows furrowed finely, and she politely reached out again and undid the strap of the book I still held, opening it to the last written page.

"Are you sure?" she suggested graciously, pointing to the page and tilting her head as if she stood right next to me.

The page was filled with what looked like my writing. And not just my writing: it was clean and even, the neatness I use when writing a card. I squatted to set down Sophie, realized I would have to juggle the coffee, stood up again to switch hands, realized I still held this strange book, then gave up and started to read. Poetry. Not a poem, exactly, but a beautiful telling of my exact morning, how I wished I could afford a maid or three, how my husband is doing his best, how Sophie is so big but still doesn't understand me, how I hoped the cafe would revive me, how it failed.

The queen mother has a cotton-gloved footman for every room’s teacups

She wouldn’t miss one to tidy my floor, make my bath a salon, tend the noise

I would form a tentacle and dangle it over and snatch maybe three

If only my body monstrified its flesh for my own sake

Instead of always for others

What I can afford is to leave clothes on the floor

The unperishables next to the sink

And let Roger be fully at work while at home

The dear, the damn lucky bastard

My bones are drained, my heart is a circus tent in a windy wedding venue

Can’t someone just let me implode, commune with my pieces,

Reform into solids, and walk once again without thinking of insides

Can’t I just settle and stare at the sky’s new star without being the nighttime too

I looked at the woman. She only looked a little sheepish for having opened it to check, for having been unable to stop reading, hoping I would feel more complimented than violated. I was simply befuddled. I hadn't been able to stop either.

I wobble, like the earth

With a diaperbag moon

Bumping between overgrowth and gravity

Roger appears and retreats down our hallway

Saying he loves me, with his detachable heart

Sophie washes me with her tides.

Solitude is for angels, silence for fossilized beasts

I need to hear the singing in the scream

Become it fully and respond

Love has bones made of many things

Appearing because of love

And yet they aren’t the love

And yet they hold it

It was clearly my life - and yet here it was profound. I tried to say thank you.

"I think you should publish it," the woman said, with a light in her eye. "When it's finished, at least."

"You would read this?" She nodded earnestly.

"I wish I could feel like you."

Like me. How do I feel? We stood on the wet asphalt for a second more.

"Well, keep it up!" And she began to hurry back towards the shops.

"Thank you!" I fervently called after her, and she turned her head, hair bouncing, to throw me a wave.

I glanced back at the journal, then looked at Sophie under my cup. How did they know? She looked up at me waiting for my decision, ready to howl if it was an unpreferred one. How does anyone know, Mama? I'm cold and you're getting distracted by something not me. I started my wobble towards the car again, my elbowpit aching and my heart spinning.

In the quiet of the car, with Sophie strapped in and reunited with Bunny, I opened the little black book again.

The scent of your body my body has made

Is an answer to all my life

I did not know the machinery of love

Until I clean you, rebundle you, and smell

Beneath powder and fresh terrycloth

What my elements respond to as truth

My own mother would look at me across the casserole

Sudden in a timeless sympathy

And I did not know how to speak to her in then

How do you speak to yourself?

I now know what she saw, but still not what to say

How do you speak to yourself?

This time I did cry. I screamed. I squeezed the covers I held open and forced them against the steering wheel. The car honked. Sophie had immediately started wide-eyed to wail with fright. I didn't want to care - but could not bring myself to scream again if it meant that Sophie would feel it leave through her lungs, too. I panted a moment, the rage and despair still pent-up and seeking escape, and suddenly the page of the journal, this strange journal, this invasive journal with its knowledge of my soul, received all my emotion. I tore the page right out of the binding. And there, with Sophie halted in her wailing, I froze in my passion about to crumple the page which was no longer a page. It was a bill. A hundred dollars. The journal still had the ragged edge of the uprooted poem, but in my hand was the crisp money. Is this an answer to prayer? I turned to another page.

My heart behind its tired eyelids

Knows it is enough

Sophie sings at my nipple

Roger sleeps at my side

Like a priest at an altar

I repeated the words as I tore the page. They sounded good in my mouth and made me shiver. The paper was thick and green, embossed with UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Another hundred. I twisted to look at Sophie. Her mouth still hung open in its little frown, not sure if she should be ready to cry. Are we okay, mama? The book had 200 pages. That's twenty thousand dollars. I could take care of you, Sophie. I mean, I could pay someone to take care of you. I could have time for myself. The poem's image of Roger sleeping collapsed on my shoulder after working and running our errands and making my dinner came to mind. He had rubbed my feet that night, too. I could also take care that Roger didn't need to work those long hours. He could spend more time with you, too. I turned in the driver's seat again to show Sophie the two bills.

She looked at me, eyes moving around my face and trying to focus. I released my mask to hang from one ear, and she brightened a little. My elements respond to the truth. How did that poem go? I looked down at the journal, spine broken and missing pages, then at the bills in my hand. The poem was gone. I looked at Sophie again. She held my gaze, then wiggled in her seat, then watched me again. What do you need, mama? I turned forward again and put the bills in the pocket at the back of the book, then closed the book with a squeak as the spine settled, and pulled the band around the front again. The book I set in the passenger seat, and I opened the door, opening the back door before closing the front, and got in next to Sophie. The sound of the parking lot stopped again when the door fell shut, and I immediately undid the carseat and the sweater. What do I need? I looked at Sophie as she nursed.

Just you, my love, just me

Just us, which for now is the same

And the things which will help you become

You, and help me to remain

About the Creator

Vincent Tavani

Many-fingered poet

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.