The War of the Currents and the Man Who Lit the World

It Was More Than a Bulb. It Was a Battle for the Future Itself.

For most of human history, the night was a dominion of shadows. Fire—from a candle's weak flicker to a gas lamp's smoky glow—was the only defiance against the dark. It was dim, dangerous, and fleeting. Taming the night required not just a new kind of light, but a new kind of power.

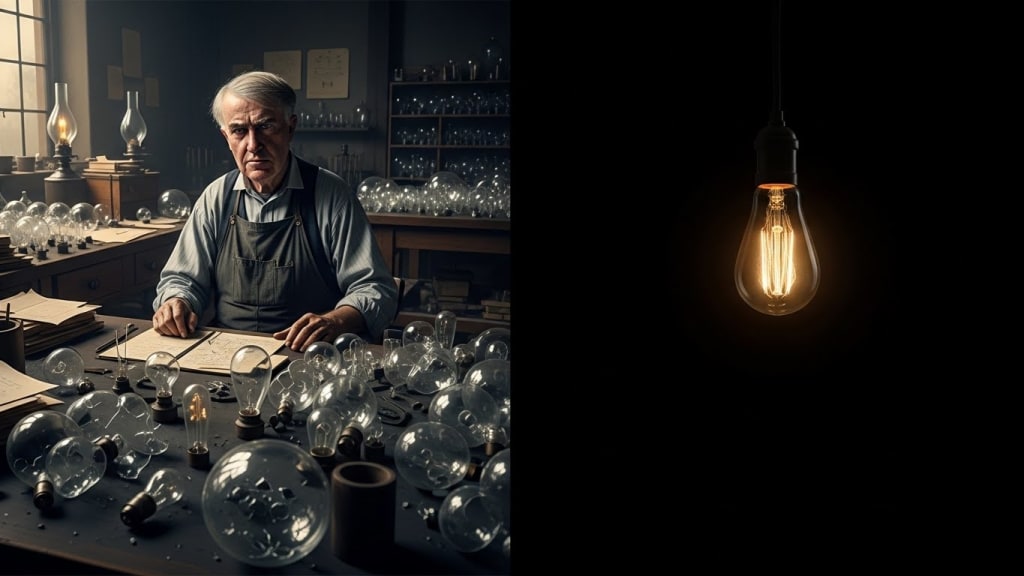

The race was on, and its most famous protagonist was Thomas Alva Edison. He was not a lone, solitary genius in a garret; he was a general, and his laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, was his factory of invention. He famously said, "Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration," and he was prepared to sweat. His method was brute-force experimentation, testing thousands of theories and materials to find one that worked.

The challenge was the filament. What material could glow white-hot inside a vacuum-sealed glass bulb without burning up? For months, the "Wizard of Menlo Park" and his team tested everything—platinum, carbon, even a hair from a colleague's beard. The lab was a graveyard of shattered glass and scorched dreams. Each failure was a step in a dark forest, but Edison, with relentless optimism, believed he was simply finding all the paths that didn't work.

The breakthrough came in 1879 with a carbonized piece of cotton thread. It was humble, almost absurdly simple. On October 22nd, they sealed it in a bulb, pumped out the air, and sent a current through it. The room held its breath. The filament began to glow—a steady, unwavering, and brilliant light. It lasted for over thirteen hours. They had done it. The incandescent electric light was born.

But inventing the bulb was only half the battle. To truly light the world, people needed a way to get that light into their homes and factories. This sparked the "War of the Currents," a fierce and sometimes brutal battle between Edison and the brilliant, enigmatic inventor George Westinghouse.

Edison championed Direct Current (DC). It was safe, he argued, but it had a fatal flaw: it couldn't travel long distances without losing power, requiring a power station every mile.

Westinghouse, backing the work of Nikola Tesla, promoted Alternating Current (AC). AC could be transformed to high voltages, sent over vast distances with little loss, and then stepped down to safe levels for home use. It was clearly the superior technology for a national grid.

Desperate to win, Edison waged a vicious public relations campaign, resorting to fearmongering. He publicly electrocuted stray animals, and even helped design the world's first electric chair using AC, trying to brand his rival's system as the "executioner's current." It was a dark chapter in the history of innovation.

But technology, in the end, cannot be bullied. The efficiency and scalability of AC were undeniable. When Westinghouse’s company won the contract to light the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, illuminating the "White City" with a breathtaking display of electrical wonder, the war was effectively over. AC had won. The world would be powered by Tesla's vision, delivered by Westinghouse.

The invention of the practical electric light did more than just push back the night. It rewired human civilization. It extended the productive day, giving us more time to work, read, and socialize. It made cities safer and streets more alive. It enabled the creation of new appliances, new industries, and new forms of entertainment. It was the foundational technology for the modern world.

So, the next time you flip a switch without a second thought, remember the war that was fought for that simple privilege. Remember the perspiration in Menlo Park, the flash of a cotton filament in a vacuum, and the battle of currents that decided how power would flow across the planet. It was more than a bulb; it was the dawn of a new age.

About the Creator

HAADI

Dark Side Of Our Society

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.