The Midnight Dance

People will leave, but their love remains.

“Hello?

Oh.

Hello Tony.”

Then silence. Poppy continued rolling out the biscuit dough on the high kitchen table, trying with every crumb of concentration to roll it evenly and to ONE CENTIMETRE like Mummy had instructed. Eventually, the silence drew Poppy’s attention away from the sand-coloured dough. From her kitchen-chair perch, she glanced at Mummy, across the tabletop resembling a battlefield of bags, flour, gaping eggshells. Mummy’s face was angry. Not surprising as it was Uncle Tony who had called. Poppy went back to rolling, back and forth. She must be very close to one centimetre now.

Mummy’s face grimaced in bemusement.

“What?” she spat. She was watching Polly across the battlefield, but another fight entirely mirrored across her eyes.

“Split equally? After all I’ve done for her?”

Another silence. Another grimace.

“Oh. You’ve done sod all! You did the least of us, swanning off-”

Polly crouched on the chair at eye-level with the dough, which was now, in her professional flour-dusted opinion, looking a little bit too thin.

“OK. Yes, I’ll come in. Then we’ll see. I want to have a proper look at the whole thing.”

Poppy put down the rolling-pin that rumbled across the table into an open bag of flour, from which a little cloud erupted on impact. Time to start cutting, then! Selecting the biggest star, she pressed its flashing blunt-knife edges into the not-so-thick dough.

“Can’t do Wednesday… I’m picking Poppy up from school.”

* * *

Poppy had been swinging her legs from the chair for what felt like a whole year. What if she’d aged in that time? Missed her birthday? She occupied herself with this existential conundrum, frowning down at her feet. Her shoes were scuffed and her little white socks dusty from playing outside during lunchtime break, under the hot blue bowl of June. She felt even hotter in this formal room, even with its blinds slicing the sun into vertical lines that striped across the empty far wall.

“But,” Mummy said firmly to the Will man, “equal distribution between four will leave us with – well - nothing worth having.”

“Ms. Stoneman, that may be the case, but my job is simply to inform you as to the contents of your mother, Margherita Broughton’s, Will and ensure fair distribution between the beneficiaries.”

He looked up at the four siblings, then at the clock behind them, hanging on a shaft of sunlight. They’d been going over this for an hour now. They were difficult, this lot.

Auntie Kath sighed loudly, almost groaned. Poppy copied her, thinking it must be the heat, and pitied Auntie Kath as an extension of her own self-pity.

“Well. That’s that then,” said Auntie Kath.

“Yeah,” agreed Auntie Pol with a bitter laugh. “Pennies, we’ll get, if we even manage to sell the house.”

“I doubt we’ll even get pennies after paying for the funeral and everything else on top of that,” chipped in Uncle Tony.

“Well, all I know is that I want that blue tablecloth, and the crockery set,” said Auntie Kath. “I’ve always wanted those, you know that. But I cannot face going through all her stuff in that damp house. You lot can share the rest out.”

“Excepting, of course, as previously stated, the specific legacy left to, as written: whichever family member finds it,” said the Will man.

The siblings shared a sarcastic laugh. The sentimental old woman must have left something symbolic, perhaps from their childhood, in an attempt to bring them together from beyond the grave. What a joke! The Will man continued.

“This item is specified as a painting by James Browning. The Midnight Dance. Are you familiar with his work?”

The four adults shook their heads in unison.

“He is a relatively sought-after artist, and The Midnight Dance has been missing for decades, so, if it turns out to be true, it could easily reach up to $20,000, or £14,500. However, it falls to you to determine the whereabouts of the painting.”

Uncle Tony laughed again - this time in disbelief - and looked at Mummy, who had already grabbed Poppy’s arm, heading for the door.

* * *

August was hot and dry. The summer holidays were long and luscious. This year Poppy spent more time than usual playing in the neighbour’s garden, because Mummy was spending a lot of time at granny’s house, or on the phone, or elsewhere. Auntie Pol had come over one afternoon, but Poppy heard them shouting in the kitchen while she played in Rose’s paddling pool. She splashed loudly to cover it up.

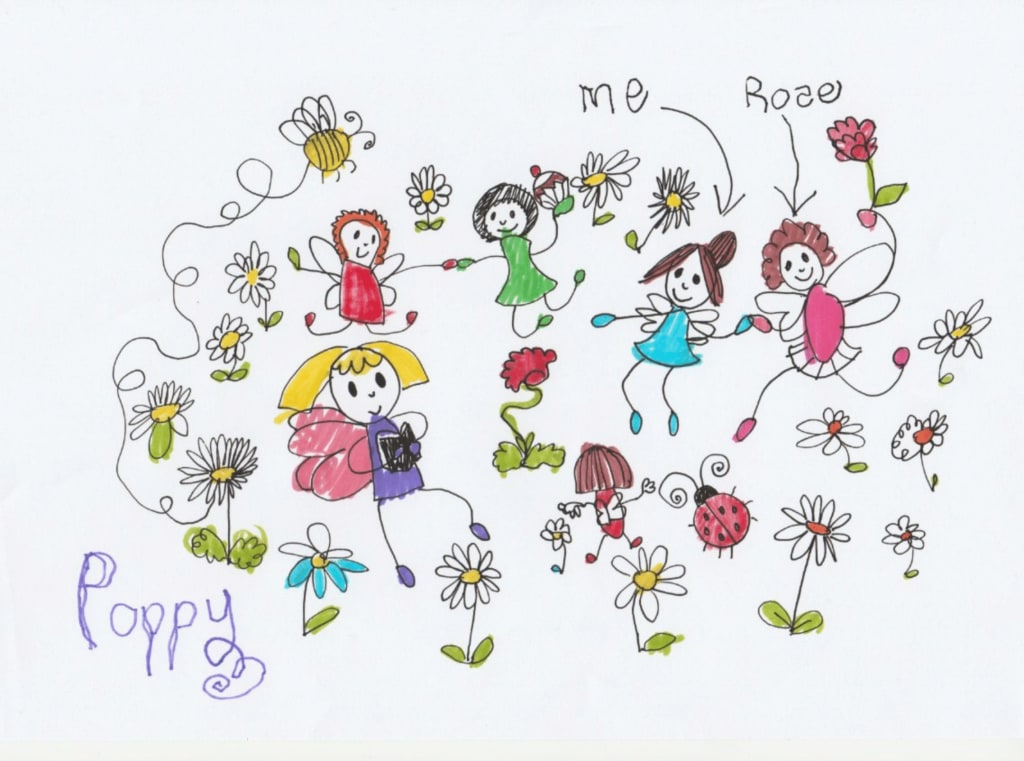

“Do you girls want to come inside and have an ice lolly?” asked Rose’s mummy. Inside the quiet kitchen, Poppy sucked the juice out of the ice gratefully. Then they did some colouring on the kitchen table. Rainbow crayons everywhere. Rose got out a little red notebook.

“I’m writing a story.”

“What about?”

Rose put her pencil to her mouth and looked up thoughtfully. “I don’t know yet. Do you want to write one?”

She gave Poppy some lined paper, but it reminded Poppy of school, and her mind became as barren as the page, as if it had sucked her ideas through its lines to where she could not reach.

That Wednesday, Mummy said “right”, and they got in the car to granny’s house. The sky had deviated from its flat summer blue, to a textured cotton-wool grey. Despite this, the air was warm and thick. They parked outside the house in its cul-de-sac, as grey as the sky save for the gardens all around. Granny’s was overgrown, but still enchanting to Poppy. Behind its picket fence, two roses stood sentinel either side of the gate: one pink, one red. Their benevolent blooms were plump, but some had already wilted to brown crisps under the sun, unpruned, stuck to the FOR SALE sign behind. Poppy stood on tiptoe to inhale an explosion of candyfloss pink. They marched down the concrete path, watched by elderly neighbours behind hedges and twitching net curtains. Daisies littered the grassy space either side of the concrete like confetti. Poppy gasped.

“A fairy ring!”

She ran up and crouched next to it, enthralled. The daisies raised their golden faces from fronds of lace bonnets. Poppy jumped delicately into the centre as if passing from one world to another, crouching there. Mummy jangled the keys like a jailor, and eventually opened the peeling front door.

“Come on. Haven’t got all day.” Extricating herself from the emotional pull of the fairy ring and running to the house, Poppy crossed the threshold into its dark hallway. It smelled funny. Mummy closed the door and put the key next to a bowl of pot pourri. Inside, the house looked like it had been turned upside down and right ways up over and over. It looked sleepy; curtains drawn, so that darkness emanated from every doorway, especially upstairs. Poppy didn’t want to go upstairs. As she moved nervously, her reflection flashed like a spirit in a mirror down the hallway.

“Right,” said Mummy, “We’ll do the loft one more time. Tony’s been rummaging, but he might not’ve checked the floorboards. That’s where it is, I reckon.”

Poppy didn’t want to go to the loft, let alone upstairs.

“Oh, for God’s sake, Poppy,” said Mummy. But Poppy wouldn’t. They opened all the curtains upstairs and it started to look a bit better in the warm grey light. But the wooden steps from the loft creaked like a pirate ship when Mummy pulled them down, and the black hole above was the gaping mouth of a monster. Mummy brought a box down and put it on the hall carpet.

“You make yourself useful, then. Don’t go wandering off!”

Poppy sat down, surrounded by a jagged shipwreck of dismantled furniture, and looked through the box. There were some random things. China figurines of a shepherdess and an owl. A basket of porcelain flowers. A jewellery box, with a ballerina inside. A memory came back from the previous autumn. Granny had shown this to Poppy. Turn the key at the back, and the ballerina pirouettes in her lace skirt, to a magical chiming tune. Try things on, my dear, I don’t wear them much these days: rings hanging like hoops on Poppy’s fingers, long beaded necklaces like daisy chains, earrings that she couldn’t wear but held in the palm of her hand like jewels. In the box were a few books, too: My First Poems, children’s stories with dog-eared dust jackets, a little black notebook. The ballerina song slowed and stopped. She felt the notebook’s soft leather in her hands, stroking its spine. Then she opened it. A delicate watercolour picture of a poppy had been taped carefully onto the inner cover, and she glowed with recognition. On the first page was written something in beautiful handwriting, and Poppy pored over this, her beaded necklaces tapping on the page like droplets of water.

To my Dearest Poppy, it began. She glowed again like a match, feeling the words with her finger as if her touch would bring them to life.

This is for you.

Try as she might, she couldn’t make out any more. She was only on the green level reading books at school, and found those difficult, although she loved making up stories in her head. She turned its smooth little pages one by one, until she reached the inside back cover. On this was stuck an image of a daisy.

Suddenly, the front door was unlocked noisily. Someone barged in.

“Hello?” Uncle Tony shouted into the silent home. Poppy peeked through the banister.

“Oh. Poppy. Where’s your mother?”

He had a shovel.

“The attic? Been through that. Kath and Pol even looked under the floorboards. Nothing. I’m going to dig over the front garden. It’s the last place I can think of. Don’t tell Mummy. I want a head start.”

* * *

“What are you doing up there? Been absolutely ages!” shouted Poppy’s mother.

“Nearly ready!”

Poppy stood in her bedroom, admiring her reflection. She fizzed with excitement as the prom dress threw out a thousand sparkles in the June sunlight. Rose would come over soon, and they would take photos. Makeup carefully applied; Poppy now just needed to choose the perfect earrings. She brought out her jewellery box from behind a pile of notebooks – a mess of journals, short stories, her precious notebook from her grandma - and opened it to the chiming ballerina, wound up and waiting patiently to be freed. Smiling, twirling to the chiming in her own swishing dress, she selected her favourite pair of imitation pearl earrings, each surrounded by petals of faux diamonds.

Poppy couldn’t see her shoes in the reflection of granny’s mirror. She took down the heavy looking-glass and propped it up to see the full image. She pressed her hands prayer-like to her ruby lips with excitement. Lifting the mirror back onto the wall, she looked behind it for the hooks. A strange outline was visible. She turned it round. Something stuck underneath? Poppy tore the backing away just an inch, which loosened something inside.

“Time, Poppy! Come downstairs!”

She lay it down and ripped off the brown backing paper. Underneath, a beautiful painting: a dancing party, twirling in a night-time circle. Poppy knelt in her small room, surrounded by golden skirts, a thousand sparkles on the walls, and The Midnight Dance in front of her.

* * *

To my Dearest Poppy,

This is for you.

I’m sorry I haven’t been able to see you much. That’s how it goes, sometimes. But I know you. I know that you will get all that you can from life. Give all that you can, too.

Use this notebook to write all your dreams for life. They will change. get bigger, or smaller, as you change. But it will be a nice reminder to see them written down. A reminder that freedom lies in them, and within you!

Your loving nonna,

Margherita

About the Creator

Katharine Amphlett

Full-time student, full-time dreamer.

New to Vocal... hoping it will give me wings!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.