The Color Line Within the Color Line

How Colorism Sustains Systems of White Supremacy Across Cultures

Colorism is often described as a preference for lighter skin within communities of color. Yet this definition, while accurate, is incomplete. Colorism is not merely an aesthetic bias or cultural quirk. It is a social technology one that developed within colonial and racial hierarchies to maintain systems of white supremacy without constant direct enforcement. At its core, colorism is a structure that rewards proximity to whiteness and punishes distance from it. It operates through psychological conditioning, social incentives, and internalized hierarchies. Over time, it becomes self-sustaining: communities begin to reproduce the same divisions that were originally imposed upon them.

In this way, colorism functions as an internal engine of oppression; one that keeps the system running even when the architects are no longer visibly present.

Colorism as a Product of Racial Hierarchy

Scholars widely recognize colorism as a byproduct of colonialism and slavery. During these periods, racial hierarchies were not only enforced between white and non-white populations but also within colonized groups themselves.

Hunter (2007) defines colorism as a system in which “lighter skin is privileged over darker skin” due to historical structures that equated whiteness with power, morality, and intelligence. Similarly, Glenn (2009) describes colorism as a global phenomenon rooted in colonial encounters that elevated European features as universal standards of beauty and worth.

In many slave societies lighter skinned individuals were more likely to work indoors.They sometimes received better clothing, education, or food.They were occasionally granted limited authority over darker-skinned individuals. This created what some scholars call a “pigmentocracy” a social system organized around gradations of skin tone. The goal was not simply efficiency but was also control. By creating internal divisions, the ruling class reduced the likelihood of collective resistance.

The Psychology of Alignment With the Oppressor

One of the most complex aspects of colorism is the psychological phenomenon in which individuals align themselves with systems that marginalize them. Several theories help explain this.

1. Survival Adaptation

Throughout history, proximity to power increased the chances of survival. Those who appeared more acceptable to dominant groups often received safer working conditions, greater mobility and reduced violence. Over generations, this produced an unconscious association between whiteness and safety.

2. System Justification Theory

System justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994) proposes that people are psychologically motivated to see the systems they live in as fair, even when those systems disadvantage them. This reduces anxiety and cognitive dissonance. Thus, if lighter skin is rewarded, individuals may begin to believe

- Lighter skin is naturally superior.

- Darker skin is naturally inferior.

- The system is “just the way things are.”

3. Internalized Oppression

Repeated exposure to stereotypes can lead individuals to adopt those beliefs about themselves and others. This is known as internalized oppression. Paulo Freire (1970) described this process as one in which “the oppressed internalize the image of the oppressor and adopt his guidelines.”; it’s like Stockholm syndrome in a way.

A System That Sustains Itself

Colorism allows racial hierarchies to function without constant external enforcement. When lighter skinned individuals distance themselves from darker-skinned peers, communities adopt hierarchies based on complexion and social opportunities follow skin tone…the system becomes self-regulating. The divisions are maintained internally. The machine runs itself.

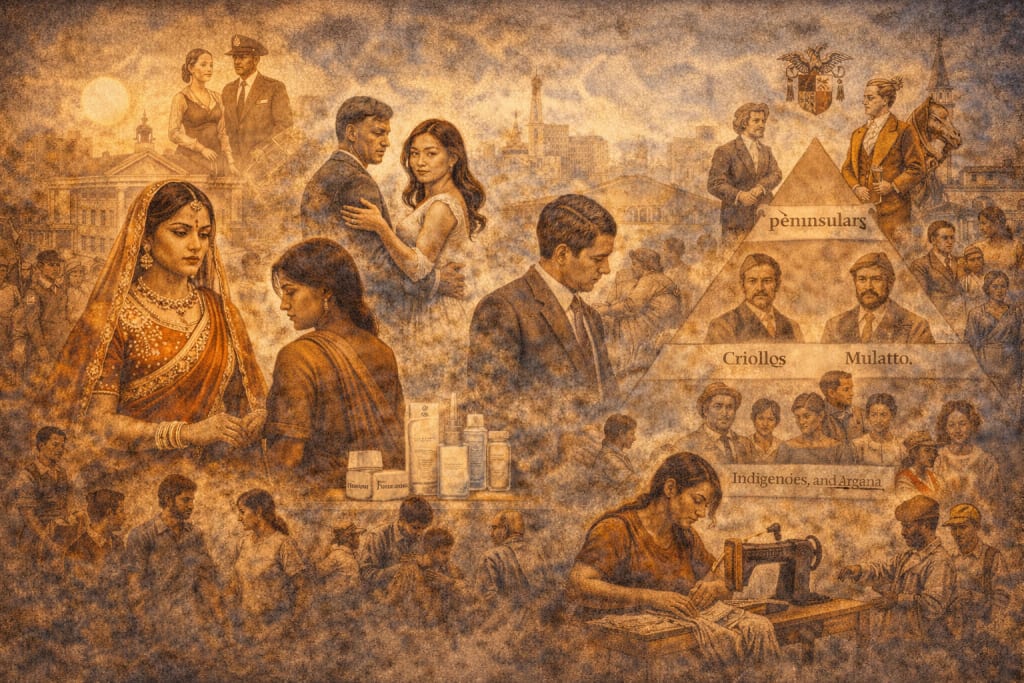

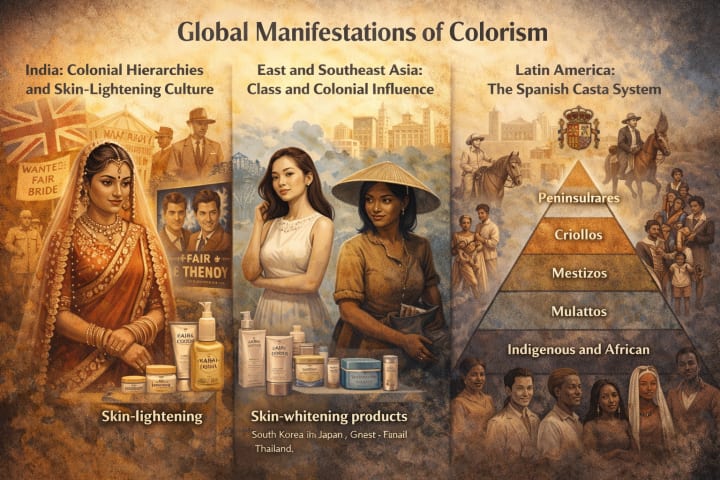

Global Manifestations of Colorism

India’s Colonial Hierarchies and Skin-Lightening Culture

In India, colorism intensified during British colonial rule. European features became associated with authority and refinement, while darker skin became linked to manual labor and lower status. Today, the legacy remains visible in marriage advertisements requesting “fair” brides, multibillion-dollar skin-lightening industry and media representation favoring lighter actors; especially as heroes and darker skin as criminal or ignorant. You’ll see this in Western media as well; hence why representation in media matters.

Scholars such as Parameswaran and Cardoza (2009) argue that colonial aesthetics reshaped indigenous beauty standards, embedding whiteness into modern Indian identity.

East and Southeast Asia: Class and Colonial Influence

In many East Asian societies, lighter skin historically symbolized wealth and indoor labor. However, colonial influence and global media intensified these ideals.

Skin-whitening products remain popular across South Korea, Japan, China, Thailand and the Philippines. These preferences are now tied not only to class but also to globalized racial hierarchies.

Latin America: The Spanish Casta System

Colonial Spanish America developed a formal racial classification system known as the casta system. https://cowlatinamerica.voices.wooster.edu/2020/05/04/the-casta-system/

People were categorized by ancestry

- Peninsulares (Spanish-born whites)

- Criollos (American-born whites)

- Mestizos (mixed European and Indigenous)

- Mulattos (mixed African and European)

- Indigenous and African populations at the bottom

Each category carried different legal rights and social privileges. This structure created a long-lasting association between lighter skin and upward mobility.

Personal and Interpersonal Colorism

Colorism is not confined to institutions. It operates within families, friendships, and relationships. In many communities siblings are treated differently based on skin tone, romantic partners are judged by complexion and parents encourage lighter partners for their children; I’ve witnessed it as many times as I overwhelmingly experience everywhere I go.

You described an experience in which a partner’s half-sister, who was half German and half Latin American and she demeaned him for being Puerto Rican and expressed hostility towards me because of my complexion. This is a direct example of colorism operating within intimate family dynamics. It illustrates how colonial hierarchies become internalized and reproduced at the most personal levels. Sometimes I wonder which half of her heritage she relates to nowadays with ICE around considering she’s not white presenting.

European Immigrants and the Shifting Boundaries of Whiteness

Whiteness has never been a fixed category. It has expanded and contracted over time, often for political and economic reasons. Groups once considered racially inferior were gradually absorbed into whiteness.

The Irish

In the 19th century, Irish immigrants were depicted in American media as ape-like, violent and intellectually inferior. They were frequently compared to Black Americans in racist cartoons and literature. Over time, however, many Irish communities gained acceptance into whiteness, particularly as they entered law enforcement and civil service, aligned politically with white power structures and distanced themselves from Black communities.

Italian Americans From “Enemy Aliens” to White Americans

Italian immigrants faced intense discrimination in the United States, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They were often portrayed as criminal, uncivilized and racially suspect. The 1911 Dillingham Commission described Southern and Eastern Europeans as inherently inferior.

Immigration Restrictions and Racial Classification

The Immigration Act of 1924 established quotas favoring Northern Europeans and drastically reduced immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. Italian immigration dropped by approximately 90 percent. During World War II, suspicion toward Italian immigrants intensified. According to U.S. government records approximately 600,000 Italian-born residents were classified as “enemy aliens.” Many faced travel restrictions, curfews, and mandatory registration and around 1,800 were detained under wartime policies.

Some were forced to relocate, barred from coastal zones, required to surrender radios and cameras and subjected to surveillance. Although Italian Americans were not interned on the scale of Japanese Americans, the policies reflected deep suspicion and racialized perceptions. By the end of the war, these restrictions were lifted, and Italian Americans were increasingly incorporated into the category of whiteness.

Urban Segregation and Neighborhood Violence

Throughout the early and mid-20th century, American cities were shaped by ethnic enclaves and racial boundaries.

In many urban neighborhoods Black and brown families were violently expelled from certain blocks; like my best friend who had been chased out of Italian neighborhoods. Housing covenants and redlining enforced racial segregation and ethnic white communities policed their neighborhoods aggressively. In parts of New York City, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, clashes occurred when Black families attempted to move into previously white or ethnic-European areas. These conflicts served a broader function. They kept working-class communities divided along racial lines rather than united along class lines.

Media, Law Enforcement, and the Reinforcement of Color Hierarchies

Colorism also appears in modern institutions. In media lighter skinned actors are often cast as leads while darker skinned individuals are overrepresented in villain roles. There’s advocacy to change it up but as a former partner stated “we tried it with your people and nobody wants to watch that” and heard many agree in silence and loudly.

In criminal justice, studies show darker-skinned defendants often receive harsher sentences than lighter-skinned individuals of the same race (Monk, 2014); even within institutions, alignment with authority does not always protect individuals.

There have been cases where people of color in enforcement roles were still subjected to racial slurs or hostility from white supremacists. These moments reveal a painful truth that proximity to power does not guarantee acceptance by it.

Colorism as a Self-Perpetuating System

Colorism sustains systems of racial hierarchy by creating internal divisions, encouraging competition for proximity to whiteness and redirecting anger horizontally instead of upward. This fragmentation weakens solidarity and reduces the likelihood of collective resistance. As a result, the system does not require constant enforcement.

It reproduces itself.

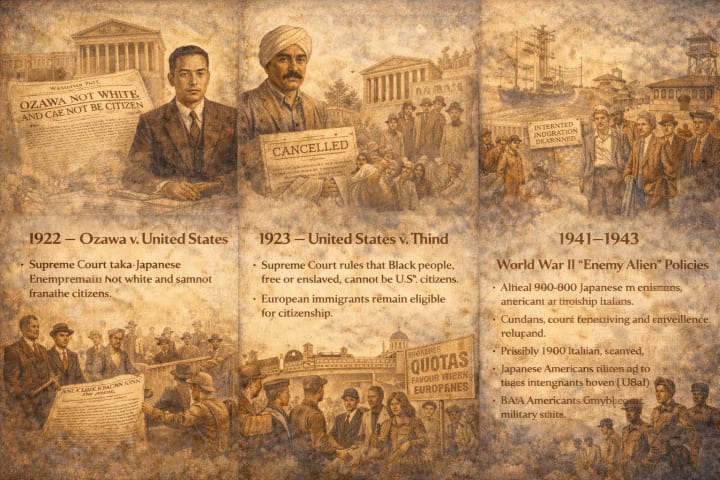

Whiteness, Citizenship, and the Unequal Path to Rights

Understanding the relationship between colorism and white supremacy requires examining how different groups were treated under American law. Not all marginalized communities experienced exclusion in the same way. Irish and Italian immigrants faced severe discrimination, violence, and legal restrictions, particularly during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, the nature of their exclusion was fundamentally different from that experienced by Black, Asian, and Indigenous populations. The difference lay not only in social prejudice, but in legal classification. European immigrants were seen as capable of becoming white, while people of color were structurally defined as permanently outside of whiteness.

From the founding of the United States, citizenship laws reflected this distinction. The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited citizenship to “free white persons,” establishing whiteness as a legal prerequisite for belonging. This meant that even when Irish and Italian immigrants were mocked, segregated, or described as racially inferior, they were still considered legally white. They were eligible for citizenship, property ownership, and voting rights once naturalized. By contrast, Asians were legally barred from citizenship, and Black Americans many of whom were enslaved were excluded from the political system entirely. Even after emancipation, Black citizens faced legal segregation, voter suppression, and systemic violence.

The Immigration Act of 1924 illustrates this difference clearly. The law imposed strict quotas that drastically reduced immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, including Italy. Italian immigration dropped by nearly ninety percent. However, these immigrants were not completely banned. They were restricted, but still recognized as part of the broader white European population. In contrast, the same law effectively prohibited all immigration from Asia. Asian immigrants were not merely restricted; they were excluded entirely. They were also barred from naturalization through court rulings such as Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Thind (1923), which declared that Asians were not white and therefore ineligible for citizenship.

The treatment of Italian Americans during World War II further illustrates this dynamic. Approximately 600,000 Italian-born residents were classified as “enemy aliens.” Many were subjected to curfews, travel restrictions, property seizures, and surveillance. Around 1,800 were detained, and some were forced to relocate from coastal zones. These policies reflected widespread suspicion and xenophobia. Yet, even in this moment of crisis, Italian Americans were not subjected to the same level of mass internment experienced by Japanese Americans. More importantly, these restrictions were temporary. By the end of the war, most limitations were lifted, and Italian Americans were increasingly absorbed into the category of whiteness.

For Black Americans and many Asian communities, however, exclusion was not temporary. It was systemic and enduring. Black Americans faced a racial caste system that extended from slavery into the Jim Crow era, where segregation, disenfranchisement, and violence were legally sanctioned. Asian immigrants were barred from naturalization, prevented from owning land in several states, and restricted to ethnic enclaves. Unlike European immigrants, these groups were not seen as potential members of the dominant racial category. Their exclusion was not framed as a stage of assimilation, but as a permanent condition.

Urban segregation further reinforced these divisions. In cities such as New York, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, neighborhoods were often divided along racial and ethnic lines. European immigrant communities, including Irish and Italian enclaves, sometimes violently resisted the arrival of Black families. Housing covenants, redlining, and mob violence ensured that Black and brown populations remained confined to certain areas. These conflicts were not only expressions of prejudice. They also served a structural purpose. By encouraging competition and hostility among working-class communities, the system prevented unified resistance against economic and political elites.

Over time, Irish and Italian Americans gained access to political power, public sector jobs, and suburban homeownership. They entered police departments, fire departments, unions, and city governments. Their integration into whiteness was gradual, but real. Meanwhile, people of color continued to face structural barriers in housing, employment, education, and voting rights. The difference was not simply one of prejudice, but of legal status and social mobility. European immigrants were positioned on a path toward inclusion, while people of color were structurally positioned outside the boundaries of the nation’s dominant racial identity.

This distinction reveals a crucial truth about American racial history. Irish and Italian immigrants were not initially treated as fully white, but they were always treated as capable of becoming white. People of color were not afforded that possibility. Their exclusion was embedded in law, culture, and social institutions. Understanding this difference helps explain how systems of racial hierarchy have persisted, and how colorism functions as a mechanism that sustains those systems from within.

Timeline of Citizenship, Exclusion, and the Boundaries of Whiteness in the United States …walk with me

1790 – Naturalization Act

- U.S. citizenship limited to “free white persons.”

- Irish and other European immigrants eligible for naturalization.

- Black people (many enslaved) and all Asians excluded from citizenship.

1857 – Dred Scott v. Sandford

- Supreme Court rules that Black people, free or enslaved, cannot be U.S. citizens.

- European immigrants remain eligible for citizenship.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/dred-scott-v-sandford

1865–1870 – Reconstruction Amendments (13th, 14th, 15th)

- Slavery abolished.

- Black men granted legal citizenship and voting rights.

- In practice, these rights are later suppressed through Jim Crow laws.

- Asians still barred from naturalization.

1882 – Chinese Exclusion Act

- First major federal law banning immigration based on race.

- Chinese laborers prohibited from entering the United States.

- Chinese immigrants barred from citizenship.

1890s–1910s – Height of Nativism

- Irish and Italian immigrants face social discrimination, violence, and job restrictions.

- Black Americans experience Jim Crow segregation and racial terror.

- Asian communities confined to segregated districts and restricted occupations.

1911 – Dillingham Commission Report

- U.S. government report labels Southern and Eastern Europeans, including Italians, as racially inferior.

- Despite this, they remain legally classified as white and eligible for citizenship.

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/dillingham-commission-reports/

1922 – Ozawa v. United States

- Supreme Court rules Japanese immigrants are not white and cannot become citizens.

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/takao-ozawa-v-united-states-1922/

1923 – United States v. Thind

- Supreme Court rules that Indian immigrants are not white under U.S. law.

- Many previously naturalized South Asians lose their citizenship.

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/thind-v-united-states/

1924 – Immigration Act (Johnson–Reed Act)

- Establishes national-origin quotas favoring Northern Europeans.

- Italian immigration reduced by about 90 percent but not eliminated.

- All Asian immigration effectively banned.

1941–1943 – World War II “Enemy Alien” Policies

- About 600,000 Italian-born residents classified as enemy aliens.

- Curfews, travel restrictions, and surveillance imposed.

- Roughly 1,800 Italians detained.

- Japanese Americans subjected to mass internment of over 110,000 people.

- Black Americans serve in segregated military units.

1945 – End of World War II

- Restrictions on Italian Americans lifted.

- Italian Americans increasingly absorbed into mainstream whiteness.

- Japanese Americans released from internment but face continued discrimination.

- Black Americans still live under segregation.

1952 – McCarran–Walter Act

- Immigration law allows Asian immigrants to naturalize for the first time.

- European immigrants fully integrated into white citizenship status.

1964 – Civil Rights Act

- Legal segregation outlawed.

- Black Americans gain formal protection against discrimination.

1965 – Voting Rights Act

- Federal enforcement of voting rights for Black citizens, especially in the South.

1965 – Immigration and Nationality Act

- National-origin quotas abolished.

- Immigration opened more broadly to Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- Marks a major shift away from explicitly race-based immigration policy.

Recognizing the Structure

Colorism is not merely about beauty standards or personal prejudice. It is a structural inheritance from colonial and racial systems designed to maintain control through division. Understanding colorism requires historical awareness, psychological insight, media literacy and honest intra-community dialogue. Only by recognizing the mechanisms behind these divisions can societies begin to dismantle them.

The Illusion of Protection Why Alignment With the Oppressor Does Not Guarantee Safety

One of the most persistent psychological effects of racial hierarchy is the belief that proximity to power will lead to protection. Within systems shaped by white supremacy, individuals from marginalized communities are often encouraged implicitly or explicitly to align themselves with dominant institutions. The promise is rarely spoken outright, but it is deeply understood: if you enforce the system, you may be spared by it. If you defend the structure, you may be accepted by it. Yet history repeatedly demonstrates that this promise is fragile, conditional, and often false.

Throughout different regimes and political systems, there have always been individuals from marginalized groups who were recruited into the machinery of control. In Nazi-occupied Europe, some Jewish prisoners were forced or coerced into administrative or policing roles within ghettos and camps. These positions were not signs of acceptance or safety. They were temporary, precarious roles within a system that ultimately viewed them as expendable. The structure did not change its fundamental ideology. It only used them as tools until they were no longer useful.

A similar dynamic appears in colonial and racial hierarchies across the world. Systems built on racial stratification often create intermediary classes—people who are given slightly more privilege, authority, or proximity to power in exchange for enforcing the system on others. These roles create the illusion of status and belonging, but they are structurally unstable. The moment these individuals are no longer useful, or the moment their racial identity becomes more visible than their institutional role, the system reminds them of where they truly stand.

Modern institutions are not immune to this pattern. In recent events in Minneapolis, federal immigration enforcement operations have sparked national controversy after multiple fatal shootings of civilians by federal agents. These incidents have intensified public debate over immigration enforcement and the role of federal agencies in local communities. In such moments, the contradiction becomes visible: individuals may serve the system, enforce its policies, and carry out its mandates, yet the racial hierarchies embedded within the society around them do not disappear. Institutional alignment does not erase racial identity, nor does it guarantee respect or protection.

The psychology behind this alignment is rooted in survival. When systems reward proximity to power, people naturally move toward what appears safer. If lighter skin, European features, or institutional loyalty are associated with opportunity, individuals may begin to internalize the belief that aligning with the dominant structure will improve their circumstances. Over time, this becomes a generational survival strategy. Parents encourage their children to “fit in,” to speak a certain way, to look a certain way, or to pursue certain careers that place them closer to the centers of authority.

But these strategies often come with a cost. Alignment may bring short-term benefits like employment, social mobility, or perceived respectability but it rarely dismantles the underlying hierarchy. Instead, it can reinforce it. The individual becomes a symbol of the system’s supposed fairness, a living example used to justify the structure. They are presented as proof that anyone can succeed if they simply work hard enough or align themselves correctly. In this way, they become what sociologists sometimes describe as a “token” someone whose presence is used to legitimize a system that remains fundamentally unequal.

History shows that tokens are rarely protected when the system is threatened. Their status is conditional, not secure. The same structure that elevated them can discard them. This is why alignment with oppressive systems does not guarantee safety. It may offer temporary access, but it does not change the underlying logic of the hierarchy.

In systems built on white supremacy, acceptance is often transactional. It depends on usefulness, obedience, and proximity to whiteness. It is not rooted in genuine equality. As a result, those who align themselves with the system may find that their position is always precarious. They are valued only as long as they serve a purpose.

This dynamic helps explain why colorism and internal divisions persist. When individuals believe that aligning with the dominant structure will save them, they may distance themselves from others in their own communities. They may adopt the biases of the system, enforce its rules, or participate in its institutions in the hope of securing a safer position. But this often strengthens the very structure that marginalizes them.

The lesson, repeated across history, is clear that systems built on racial hierarchy do not offer true protection to those they classify as inferior. They offer conditional acceptance at best. Alignment with such systems may provide short-term advantages, but it rarely leads to genuine security, dignity, or equality. Instead, it often turns individuals into instruments of a structure that does not ultimately value their humanity.

Maybe try looking up…

Equality is not oppression

Colorism thrives on division, but the system it serves has always depended on keeping ordinary people from realizing they were never meant to be enemies. Only by recognizing the mechanisms behind these divisions can societies begin to dismantle them.

*********************************************************************

References

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Glenn, E. N. (2009). Shades of Difference: Why Skin Color Matters. Stanford University Press.

Hunter, M. (2007). “The Persistent Problem of Colorism.” Sociology Compass.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). “The Role of Stereotyping in System Justification.” British Journal of Social Psychology.

Monk, E. P. (2014). “Skin Tone Stratification Among Black Americans.” Social Forces.

Parameswaran, R., & Cardoza, K. (2009). “Melanin on the Margins.” Journalism & Communication Monographs.

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/italian/under-attack/#:~:text=From the late 1880s, anti,than 20 Italians were lynched.

https://sytbt.davidson.edu/soc105/italian-immigration/

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/02/opinion/illegal-immigration-italian-americans.html

https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2868&context=nmhr

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/dred-scott-v-sandford

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/60/393/

https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2008/10/06/negative-stereotypes-of-the-irish/

https://thomasnastcartoons.com/irish-catholic-cartoons/irish-stereotype/

https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/640

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/dillingham-commission-reports/

https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/stories-from-the-archives/highlights-from-the-library-collection-immigration-commission-reports

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/takao-ozawa-v-united-states-1922/

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/thind-v-united-states/

https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=historical-perspectives

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

https://colorismhealing.com/white-people/

https://medium.com/afrosapiophile/why-denying-light-skinned-privilege-doesnt-make-it-go-away-a2136f5fd16b

https://www.laurabelmba.com/race-table-talks-blog/the-complex-interplay-of-white-supremacy-and-colorism

https://thebeautywell.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Colorism-within-media.pdf

https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1078&context=efl_fac_pubs

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1301308.pdf

https://ijme-journal.org/index.php/ijme/article/view/2457

https://research-archive.org/index.php/rars/preprint/download/173/385/233

https://ldad.org/letters-briefs/whitewashing-history

https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/restoring-truth-and-sanity-to-american-history/

https://thehill.com/opinion/white-house/5223544-trump-executive-order-revises-american-history/amp/

About the Creator

Cadma

A sweetie pie with fire in her eyes

Instagram @CurlyCadma

TikTok @Cadmania

Www.YouTube.com/bittenappletv

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (3)

AMEN. I am impressed.

WOW. I taught Mythology for years at a university. I changed it to World Mythology. I am part Sri Lankan, Han Chinese, Colombian-Peruvian and my mother escaped North Korea. My uncle was Japanese Hawaiian.

That is some break down. But that definitely is our history. Puts in mind the phrase our government wouldn’t do that. Yup they would they did it before.