American Manufacturing Isn't "Coming Back"

Not Gonna Happen

The nascent trade war was begun by the Trump administration ostensibly to level trade imbalances the United States has with its trading partners, no matter how much they pretend the tariffs are reciprocal.

An added benefit the administration would like us to believe is a reversal of the decline in manufacturing in the United States so profound the country will enter into an industrial golden age. Like most hagiographies of the halcyon days, this one is hallucinatory. Put plainly, manufacturing is not returning to the United States.

Before diving into why, it’s important to understand what is meant by “manufacturing returning to the United States.” What the administration professes to lament is the loss of manufacturing jobs, not manufacturing output, i.e., the amount and dollar value of manufactured goods produced every year.

So, for purposes of discussing whether manufacturing will return to the United States, manufacturing refers to jobs, not output.

Tariffs will certainly not achieve the revitalization of manufacturing pined for by the deluded. The sobering reality is nothing will, for two salient reasons:

Labor in the United States is too expensive

Increased manufacturing output is unlocked primarily by increased labor productivity

Labor in the United States is Too Expensive

The first point is easier to understand. Tariffs are meant to make imported manufactured goods cost more, thus incentivizing producers to manufacture in the United States.

On its face this is a cogent argument, but reality often differs from valid logic. As an aside, the administration says out of one side of its collective mouth tariffs are meant to increase prices of some goods to spur domestic manufacturing, but out of the other side says they’ll lower prices. The contradiction belies just how incoherent the Trump administration’s strategy is, as far as it can be said to have a strategy.

Supporters of the tariffs as economic catalysts argument only validate their critics by premising their views on the notion that manufacturing goods in the United States will not only be cheaper than importing them, but somehow cheaper than they were before the trade war began. It’s a truly outrageous notion that willfully overlooks a blatantly obvious fact in particular.

The offshoring of labor, manufacturing being no exception, is primarily done for one specific purpose - to lessen its cost.

It is no secret that rising industrial powerhouses, most notably China, but also many of their neighbors, particularly those with large populations in need of work, such as Vietnam, Pakistan, and India, compensate their factory workers far less than the United States and other developed countries.

It’s not a stretch to say the factory wages in those countries are a fraction of those in wealthy developed countries. Foxconn’s iDPBG, the producer of iPhones, pays its workers an average of $2.88/hour, far below even the stingiest minimum wage in the United States.

And that just scratches the surface. It says nothing of associated costs, such as any benefits, taxes, and compliance with federal and state safety regulations meant to prevent Americans from being mained or killed on the job. On the other hand, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) does not care if manufacturers work their employees to death. Their attitude is “there’s plenty more where that comes from.”

When you add up all the costs of labor in the United States, such as providing a living wage, benefits, and workplace safety protections, the incentive to hire additional American workers is almost nonexistent, and tariffs won’t motivate manufacturers to do so.

Manufacturing Output is Unlocked by Productivity Gains

It’s important to distinguish, as I did earlier, between manufacturing jobs and output in the context of the broader discussion on manufacturing in the United States because they’re both important considerations and, in a modern context, have less of a corollary relationship than any time in history.

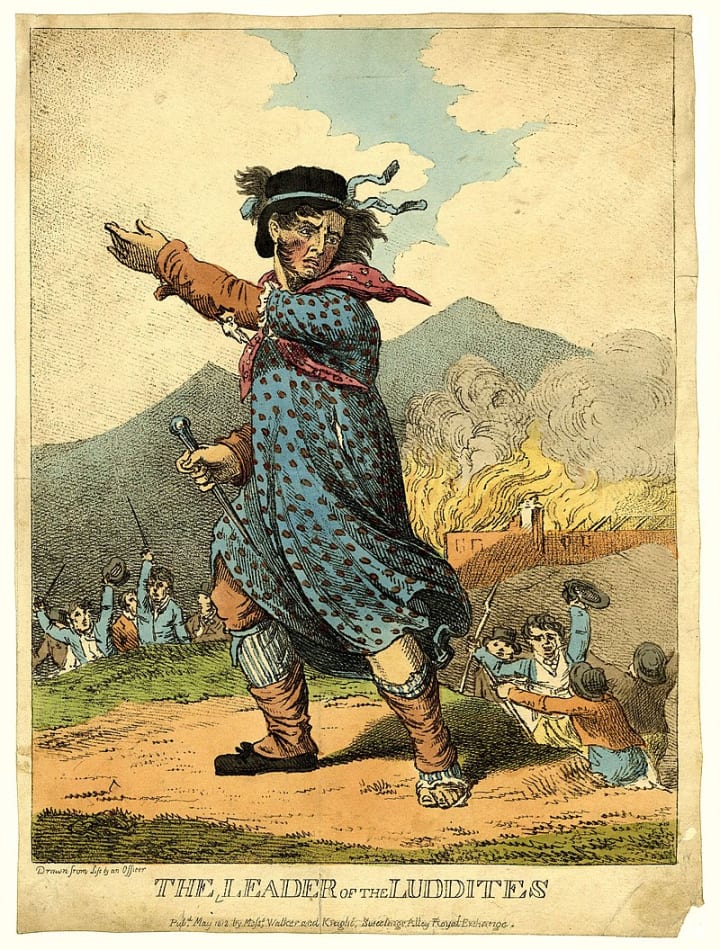

You may have heard the story of the Luddites, the original anti-technology crusaders. They were textile workers in the United Kingdom in the early 19th century when the industrial revolution was thriving.

Feeling threatened, rightly so, by the advent of automated machinery that produced textiles far faster, (thus requiring fewer textile workers), the Luddites went around smashing textile weaving machines.

Why this aside about the Luddites? Their example helps prove my point; increased manufacturing productivity is the result of several factors having nothing to do with adding workers.

One of the most obvious contributors to greater manufacturing capacity is technology. No one would disagree that the modern world can produce more textiles far more quickly than it did two hundred years ago, and that’s got a lot less to do with hiring more textile workers than it does with better machines. And this holds true across virtually all types of manufacturing today.

Other contributors to manufacturing efficiency are increased worker skills and manufacturing processes. A great example of combining better technology and superior processes to increase industrial output that has stood the test of time is how Henry Ford built Ford Motors by manufacturing cars on an assembly line and employing the division of labor principle, which every business of significant size and output has availed itself of since.

And the facts bear this all out. American manufacturing employment peaked in 1979, with 19.6 million workers before declining to 12.8 million in 2019, a decrease of 35 percent. During the period 1987 to 2024, manufacturing labor productivity increased by 129%.

The implication is obvious. Whatever gain in output the United States will achieve, which is really the point of manufacturing, will not be achieved by hiring many more workers.

When the high costs of manufacturing labor in the United States are paired with the fact that productivity is mostly increased by improved technology and process innovations, the conclusion is inescapable; explosive growth in manufacturing jobs is not part of the United States’ future.

About the Creator

Brain Juice

Wise ass from NYC and fervent storyteller. Writing about all things topical with flair, imagination, and wit. No AI generated content, just a little editing. All opinions expressed are solely my own, which is what makes them great.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.