The Guillotine: Blade of Revolution and Relic of Justice

In the late 18th century, as France convulsed in the throes of revolution, one device came to symbolize both swift justice and the terror of the new age — the guillotine. Conceived as a humane method of execution, it quickly became a chilling emblem of political upheaval and death.

The guillotine’s story is far more complex than the blood-spattered images etched into popular imagination. It is a tale of innovation, morality, and the shifting tides of justice, spanning from its first public strike to the final drop of its blade in the late 20th century.

Origins: A “Humane” Death Machine

Before the French Revolution, executions in France were brutal and uneven. Nobles were beheaded with swords or axes — often requiring several clumsy blows — while commoners were hanged, burned, or broken on the wheel. Enlightenment ideals, however, demanded equality in death.

In October 1789, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a physician and member of the French National Assembly, proposed a mechanical beheading device. Guillotin himself did not invent the machine; he simply championed the idea, believing it would ensure a quick, painless death for all, regardless of class.

The actual design came from Dr. Antoine Louis, secretary of the Academy of Surgery, who refined the concept and oversaw its construction. Parisian harpsichord maker Tobias Schmidt built the first working model in 1792. With its angled steel blade, tall wooden frame, and gravity-powered drop, it promised instant decapitation.

The First Death

On April 25, 1792, the guillotine was tested for the first time on a human. The condemned was Nicolas Jacques Pelletier, a highwayman convicted of murder and robbery.

Crowds packed the Place de Grève in Paris, eager to see this “modern” execution. The blade fell cleanly, ending Pelletier’s life in an instant. Some spectators complained it lacked the drama of older methods, but the authorities hailed it as efficient and merciful.

From that day, the guillotine became the official method of execution in France.

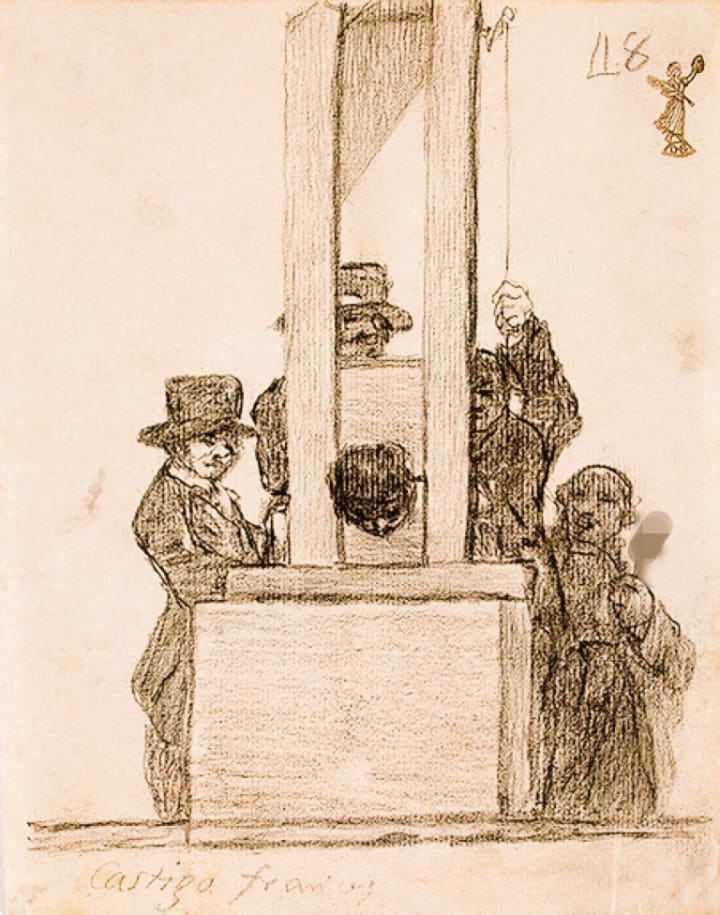

The Reign of Terror: Blade of the Revolution

What began as a rational reform soon became a blood-soaked instrument of political purging. During the Reign of Terror(1793–1794), the guillotine claimed tens of thousands of lives in Paris alone, and countless more in the provinces.

Famous victims included:

Louis XVI– Beheaded on January 21, 1793, before a massive crowd in the Place de la Révolution.

Marie Antoinette – Executed on October 16, 1793, dressed in plain white after her royal finery was stripped away.

Georges Danton, Maximilien Robespierre, and other revolutionary leaders — proof that the guillotine spared neither monarchy nor its overthrowers.

Public executions became almost daily events. Vendors sold refreshments and pamphlets as if it were theater. The blade became not just an instrument of justice, but a spectacle.

Mechanics of Death

The guillotine’s reputation for speed and certainty came from its design:

The Frame: Around 14 feet tall, sometimes painted red during the Revolution to symbolize blood and justice.

The Blade: Heavy, angled steel weighing about 40 kilograms (88 pounds), honed to a lethal edge.

The Lunette: Two semicircular grooves that locked the prisoner’s neck in place.

The Release Mechanism: A rope or lever that released the blade, sending it racing down greased grooves.

Gravity did the rest. In less than a second, the head fell into a wicker basket, while the body was removed swiftly.

Executioners, such as the famous Sanson family, were trained professionals — not sadistic brutes, but men who prided themselves on efficiency.

Beyond France: Europe’s Adopted Executioner

The guillotine’s efficiency and “humaneness” led other nations to adopt it.

In Germany, it was known as the Fallbeil (“falling axe”).

Belgium used it as the official execution method well into the 20th century.

Sweden employed it for two executions in 1910.

Still, nowhere did it gain the same notoriety as in revolutionary France.

The Last Drop of the Blade

Remarkably, the guillotine remained France’s official execution method into modern times. Public executions ended in 1939, but private ones continued behind prison walls.

The final guillotine execution occurred on September 10, 1977, in Marseille. The condemned was Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian immigrant convicted of kidnapping, torturing, and murdering a young woman.

By then, most of the world had abolished such punishments, and France’s clinging to the guillotine felt like a relic of another age. Four years later, in 1981, France abolished the death penalty entirely — ending the guillotine’s 189-year reign.

Legacy: Justice or Terror?

Today, the guillotine survives mostly in museums, films, and the cultural imagination. Some view it as a product of Enlightenment values — the first execution method designed to be equal for all. Others see it as a merciless engine of political violence.

Its stark silhouette — tall frame, gleaming blade, empty basket — still provokes unease. Perhaps because it forces us to confront two uncomfortable truths: that even noble ideals can be twisted into tools of horror, and that efficiency in killing does not lessen its finality.

Final Thoughts

The guillotine’s history is a paradox. Born from the desire for humane justice, it became one of the most infamous symbols of political violence in history. It leveled kings and commoners alike, sparing no one in its impartiality.

From Nicolas Jacques Pelletier’s swift execution in 1792 to Hamida Djandoubi’s final moment beneath the blade in 1977, the guillotine was both the great equalizer and the great terror.

Its story is not just about a machine — it is about the society that created it, the ideals it sought to uphold, and the dark reality of how those ideals were enforced. In that sense, the guillotine’s shadow stretches far beyond the scaffold, into the deepest questions of justice, morality, and humanity itself.

About the Creator

E. hasan

An aspiring engineer who once wanted to be a writer .

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.