Diogo Alves: Lisbon’s ‘Aqueduct Murderer’—The Man, the Myth, and the Head in a Jar

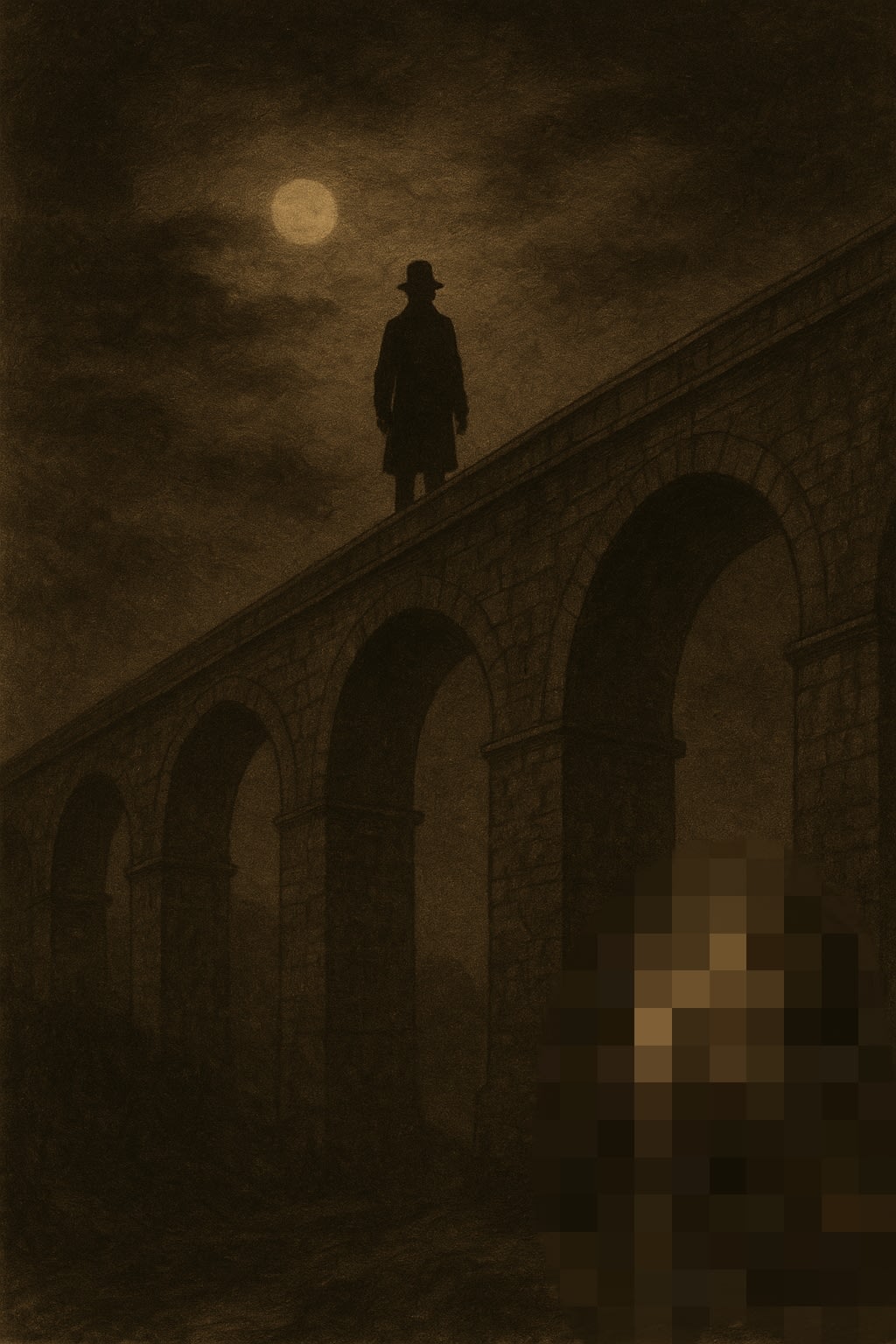

Lisbon, 1830s. The city’s famed Águas Livres Aqueduct stretched across the Alcântara Valley like a ribcage of stone, towering 65 meters above the ground. For decades, it had carried water to a thirsty city. But in the public’s imagination, it would soon carry something else—whispers of murder.

At the center of the tale was a man named Diogo Alves—a farm boy from Galicia, Spain, who came to Lisbon in search of work and left his mark in infamy. By the time the rope tightened around his neck in 1841, he was branded “O assassino do Aqueduto”—The Aqueduct Murderer.

But as with many legends, the truth is far messier.

Early Life and Descent into Crime

Born around 1810 in Galicia, Alves came from a humble background. In Lisbon, he worked as a servant and later in odd jobs. Over time, he fell into bad company and began committing petty thefts. The capital in the 1830s was turbulent—poverty, political instability, and weak law enforcement made it fertile ground for thieves.

Alves had charm but no scruples. He soon graduated from petty theft to violent robbery.

The crimes that sealed his fate took place far from the aqueduct’s arches—inside the home of Dr. Pedro de Andrade, a respected physician. Alves had learned that the doctor’s family kept valuables in their residence. In October 1839, Alves broke in and murdered four members of the household—Andrade’s elderly mother, his wife, his niece, and a servant. Later that night, he killed another servant, Manuel Alves, to eliminate a witness.

Five lives ended for little more than trinkets and coin.

The Aqueduct Murders—Myth vs. Reality

By the time Alves was captured, Lisbon was already buzzing with grim tales of travelers who had fallen—or been pushed—from the aqueduct into the rocky valley below. Between 1836 and 1839, dozens of bodies were recovered from beneath its arches. Officially, these deaths were recorded as suicides, but the idea of a murderous figure haunting the aqueduct soon took root.

Later storytellers connected these deaths to Alves, imagining him lying in wait for victims, robbing them, and then shoving them to their doom. In some retellings, he murdered over seventy people this way.

The reality? Not a single contemporary court record or newspaper of the time mentions Alves being investigated for these aqueduct deaths. He was tried and executed for the murders of Dr. Andrade’s family—nothing more.

The “Aqueduct Murderer” image was a creation of sensational pamphlets and lurid fiction written after his death, cementing his place as a bogeyman in Portuguese folklore.

The Trial and Execution

Alves’s trial was straightforward and damning. Eyewitnesses, stolen property, and his own incriminating behavior sealed his fate. He was sentenced to death by hanging—the standard punishment for capital crimes in Portugal at the time.

On February 19, 1841, crowds gathered at Lisbon’s Cais do Tojo to witness the execution. Public hangings were both spectacle and warning; for many, seeing Alves’s lifeless body swaying from the gallows confirmed the end of a reign of terror.

But his story wasn’t over.

Phrenology and the Head in a Jar

In the mid-19th century, phrenology was all the rage in Europe. This now-discredited pseudoscience claimed that the shape of a person’s skull could reveal their character, intelligence, and even criminal tendencies. For the phrenologists of Lisbon, Alves presented a perfect opportunity: the skull of a notorious murderer, ripe for “scientific” study.

Immediately after his execution, Alves’s head was severed and preserved in a glass jar filled with formaldehyde. The head was reportedly part of the collection of José Lourenço da Luz Gomes, a physician fascinated by phrenology.

Visitors could marvel at the preserved face—eyes wide open, expression frozen in death—as if searching for some visible mark of evil in the contours of his brow or the slope of his nose. The head eventually made its way to the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Lisbon, where it remains to this day.

No groundbreaking phrenological discoveries emerged from this morbid trophy. But the head itself became a curiosity—an artifact of a time when science, superstition, and spectacle freely overlapped.

A Legend That Refuses to Die

For nearly two centuries, Alves’s name has lingered in the Portuguese imagination. Tour guides point to the aqueduct and tell the story of the man who preyed on travelers. True-crime enthusiasts share photographs of the preserved head online, equal parts fascinated and repulsed.

And yet, the deeper one digs, the clearer the distinction becomes between Alves the man and Alves the myth. His confirmed murders were horrific enough. But the image of him as a serial killer tossing dozens of victims from the aqueduct appears to be nothing more than a dark invention of popular lore.

A Modern Twist—Doubts About the Head

Recently, historian Miguel Carvalho Abrantes has raised doubts that the preserved head even belongs to Alves. His research points to inconsistencies: the facial features don’t match period descriptions, the preservation method may not have been available in Lisbon in 1841, and museum records are incomplete.

If Abrantes is correct, the “head of Diogo Alves” may be yet another layer of myth—a curiosity mislabeled and mistaken for the real thing for over a century.

Why His Story Still Matters

The tale of Diogo Alves is more than a slice of lurid history—it’s a case study in how society builds legends from fragments of fact. The real man was a murderer whose greed destroyed lives. The fictional version became a phantom of the aqueduct, a faceless predator in the night.

It’s a reminder that crime stories are often shaped as much by what people want to believe as by what actually happened.

In Alves’s case, those beliefs have kept his name alive long after his body—if not his head—was buried.

---

Author's note: I am having my doubts as I write this. I ended up digging a bit more and came across that the head in the jar may not belong to the infamous murderer , according to Wikipedia. It says on there that a fire had broken out in which the catalogue of that institution was lost. So according to Wikipedia it's entirely plausible that they had mixed up a different specimen into this. Honestly, I think I believe the Wikipedia more.

About the Creator

E. hasan

An aspiring engineer who once wanted to be a writer .

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.