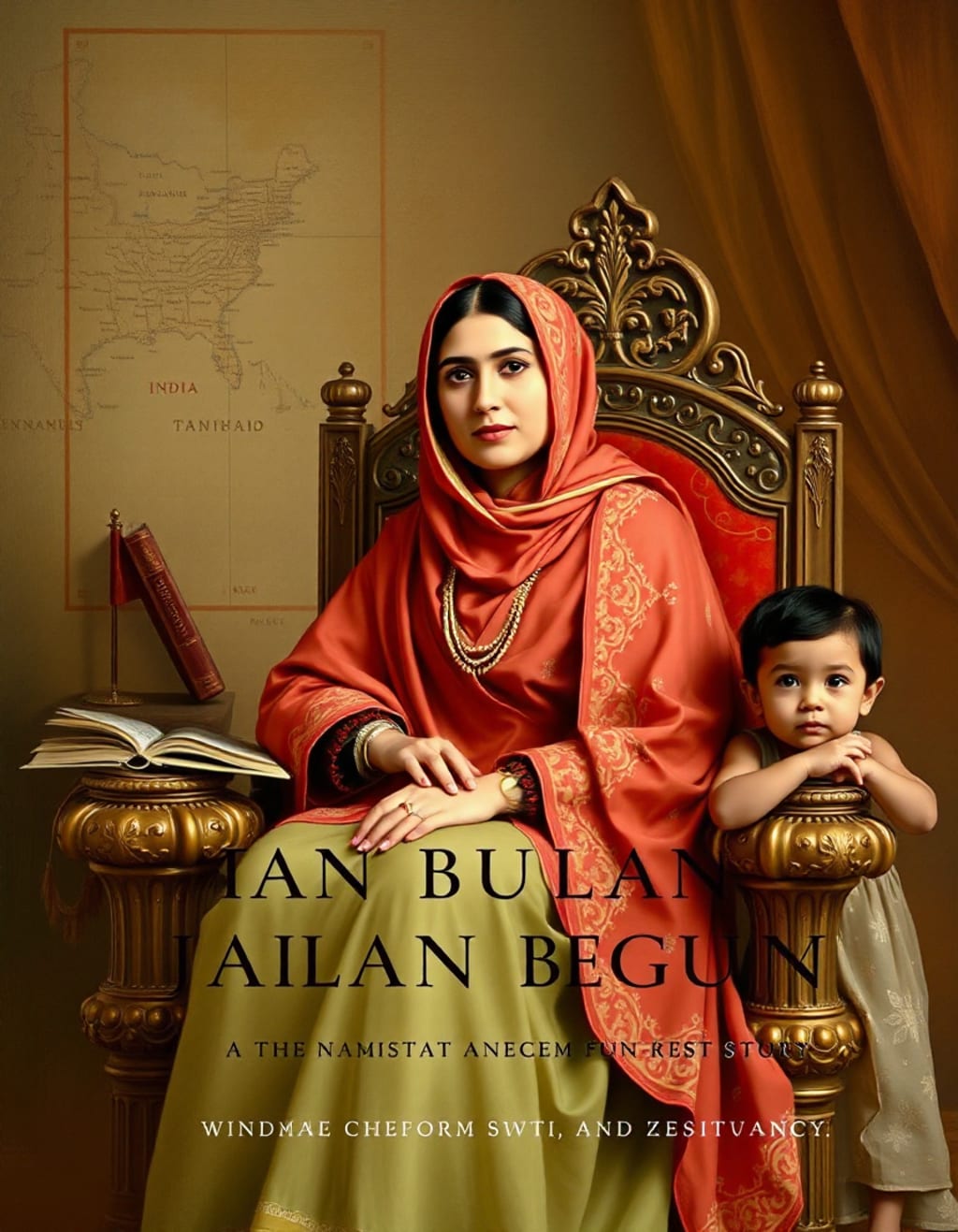

The Veiled Queen of Bhopal: How Nawab Sultan Jahan Fought Colonialism with Education

Long before independence, one Muslim queen defied British rule not with armies — but with literacy, public health, and justice.

The Silent Thunder of Reform

In the heart of British India, amidst a time of suppression, colonial dominance, and social stagnation, emerged a woman who would re-write the narrative of Muslim women in power — Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum of Bhopal.

Born on July 9, 1858, the same year the British Crown formally took over India after the mutiny of 1857, Sultan Jahan’s life would become a poetic response to the oppression that marked her birth. She wasn’t just a ruler. She was a revolutionary — one who governed in silence, but thundered through history with her reforms.

The Legacy of Powerful Women in Bhopal

The princely state of Bhopal had long been governed by a line of powerful women — unique in the patriarchal world of South Asia. Sultan Jahan’s grandmother, Nawab Sikander Begum, and her mother, Shah Jahan Begum, had already created a foundation of Muslim female leadership in India.

But Sultan Jahan, who became ruler in 1901, would take this legacy further than anyone dared.

A Queen with a Vision Beyond Palaces

When most princely rulers were busy pleasing the British with ballrooms and banquets, Sultan Jahan invested in schools, clinics, and sewers.

She established the first municipal body in Bhopal, laid modern water pipelines, enforced sanitation laws, and created one of the most progressive health systems in India. Smallpox vaccination? She made it compulsory. Public hospitals? She built them across her state.

But it was education — especially for Muslims and women — that truly defined her reign.

The Mother of Muslim Women’s Education

At a time when the idea of women attending school was seen as scandalous in many parts of India, Sultan Jahan opened the Sultania Girls’ School, established a women-only teachers’ training college, and gave stipends to girls so that families would be encouraged to send them.

She believed that a nation cannot rise without educating its mothers, and she lived that belief every single day of her reign.

She also became the first woman Chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University — a post she held from 1920 to 1926. No other woman, Muslim or non-Muslim, had ever held such a position in any major university of the subcontinent.

An Islamic Reformer in Hijab

While some Westerners misunderstood her veil as a symbol of oppression, Sultan Jahan used it as a symbol of Islamic strength, intellect, and grace. She held strong religious values but was deeply reformist. She encouraged ijtihad (independent reasoning), and her writings on women’s health, hygiene, and civic duty were circulated across Muslim India.

She authored several books and manuals — including one titled Talim-e-Niswan, which provided guidance on the proper upbringing and education of women in Islamic households.

Balancing Faith and Reform

Sultan Jahan Begum defied the binary of Western modernity versus Islamic tradition. She carved a third path: Islamic progressivism.

She reformed the Sharia courts in her state, modernized the madrasas, and emphasized science and medicine as essential fields for Muslim children. She even issued legal reforms that protected women’s rights in inheritance and marriage — centuries ahead of the Indian legal system.

A Diplomatic Genius in the Shadow of Empire

The British often feared nationalist princes, but Sultan Jahan mastered the art of cooperation without submission.

She used British alliances to build her state, gain recognition, and protect Bhopal’s autonomy. But behind the scenes, she quietly resisted cultural colonization by strengthening Muslim institutions, promoting Urdu, and resisting forced Anglicization of her schools.

She was honored with the Order of the Indian Empire by the British — yet it was her people, not the Crown, who sang her praises.

Stepping Down, But Never Away

In 1926, she voluntarily abdicated the throne in favor of her son, Nawab Hamidullah Khan — making her one of the very few rulers in Indian history to do so without pressure or rebellion. But she remained active in social reform, women's welfare, and Islamic education until her death in 1930.

Legacy That Lives in Silence

Today, her palaces may be quiet, and her name may not be in every textbook — but the hospitals, schools, and laws she built still serve millions.

She proved that a Muslim woman in hijab could rule not just a palace, but a state — with justice, modernity, and love for her people.

About the Creator

rayyan

🌟 Love stories that stir the soul? ✨

Subscribe now for exclusive tales, early access, and hidden gems delivered straight to your inbox! 💌

Join the journey—one click, endless imagination. 🚀📚 #SubscribeNow

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.