The Vanishing Visionary: "The Untold Story of Zitkála-Šá and Her Fight for Native Identity"

Story of Zitkála-Šá

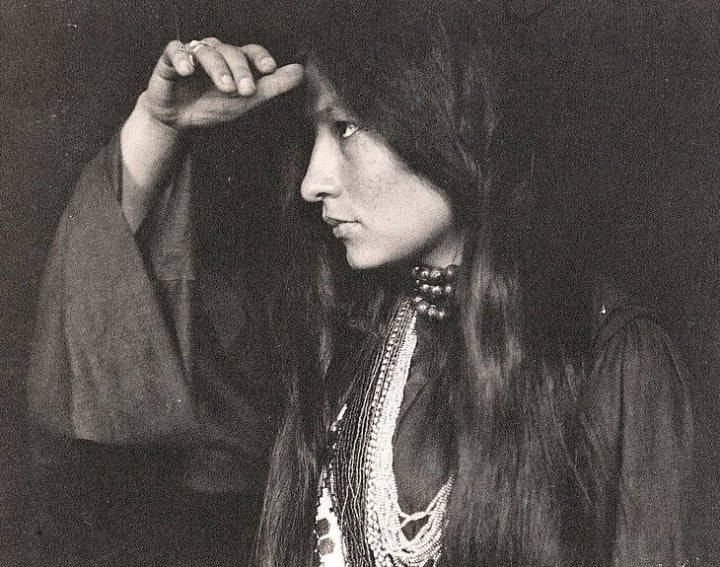

History is a story told by those in power, shaped by whose voices they choose to preserve and whose they decide to silence. Among the many voices lost or overlooked is that of Zitkála-Šá, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, a remarkable Yankton Dakota woman whose life and work embodied resistance, creativity, and the struggle for Native identity in an era determined to erase it. Her story reveals not only the pain of cultural destruction but also the power of resilience and the enduring fight for justice. Yet for decades, her legacy was buried beneath the dominant narratives of American history, only now beginning to reemerge with the strength it deserves.

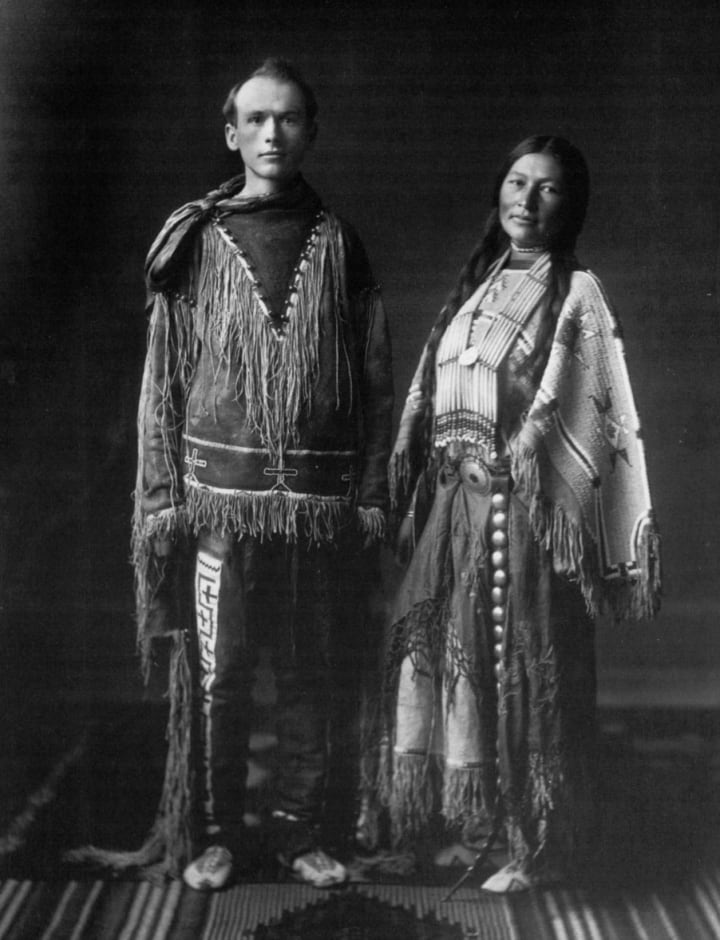

Born on February 22, 1876, on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota, Zitkála-Šá was baptized as Gertrude Simmons but was given a name rich with meaning: “Red Bird.” From the start, her life was entwined with the rhythms and teachings of the Dakota people. She grew up surrounded by the oral traditions of her community—stories that passed down the values, histories, and spirits of her ancestors. She spoke Dakota fluently, learning the language of her people before she ever learned English. Her childhood was filled with tribal ceremonies, communal storytelling, and a deep connection to the land. The natural world, the sacred rituals, and the collective memory of her people shaped her worldview and instilled in her a deep respect for her heritage.

This grounding in Dakota culture gave Zitkála-Šá a profound sense of identity. But the late 19th century was a turbulent time for Native Americans. The United States government was aggressively pursuing policies aimed at assimilating indigenous peoples into Euro-American society, often through violent and coercive means. The Dawes Act of 1887, which sought to break up tribal lands into individual allotments, and the widespread use of Indian boarding schools were tools designed to dissolve Native cultures and replace them with Western norms.

Forced Assimilation: The Boarding School Experience

At just eight years old, Zitkála-Šá was taken from her home and sent to the White’s Manual Labor Institute, a Quaker missionary boarding school in Indiana. This forced separation from her family marked the beginning of a traumatic and defining chapter in her life. The school, like many boarding schools designed for Native children, operated with the explicit mission of erasing indigenous identities. Upon arrival, her hair—long and cherished as a symbol of her identity—was cut off, a violent act meant to sever her connection to her culture. She was forbidden from speaking her native language or practicing any of her traditional customs.

The psychological trauma inflicted on these children was immense. They were punished for acts as simple as speaking Dakota or expressing grief for their lost culture. These schools isolated children from their communities, eroding family bonds and inflicting emotional scars that often lasted a lifetime. Zitkála-Šá’s writings vividly recount the loneliness and cultural dislocation she experienced.

Yet despite the oppressive environment, Zitkála-Šá demonstrated remarkable resilience. She learned English and excelled academically, recognizing that mastering the language and tools of the colonizers could provide her with a platform to tell her people’s stories and fight for their rights. Her boarding school experience was not just a story of victimization but also of resistance, a theme that would shape her entire life’s work.

Finding Her Voice: Literary Activism

Zitkála-Šá was among the first Native American writers to gain national attention. Using the English language—the language of the very culture that sought to erase her—she began publishing essays, short stories, and autobiographical works that offered an unflinching look at Native American life, especially the trauma of assimilation policies.

Her 1921 book American Indian Stories remains a landmark in Native American literature. These essays and stories blend personal narrative with broader social critique. In them, she explores the wrenching conflict between her Dakota heritage and the forced adoption of white American culture. She writes poignantly of the sense of loss and fragmentation experienced by Native people caught between two worlds.

In addition to her autobiographical works, Zitkála-Šá published Old Indian Legends in 1901, which preserves Dakota myths and folklore. Unlike many contemporaneous accounts by non-Native writers who often distorted or appropriated indigenous stories, Zitkála-Šá’s retellings were rooted in respect and authenticity. Through these stories, she preserved the spiritual and cultural essence of her people, ensuring that these legends would not be forgotten despite the pressures to erase Native traditions.

Her literary style was groundbreaking—not just in content but in form. She blended traditional oral storytelling techniques with Western literary forms, creating a hybrid voice that spoke to both Native and non-Native audiences. This duality reflected her own life’s tension but also her mission to bridge cultural divides and foster understanding.

Musical Contributions: Bridging Cultures Through Art

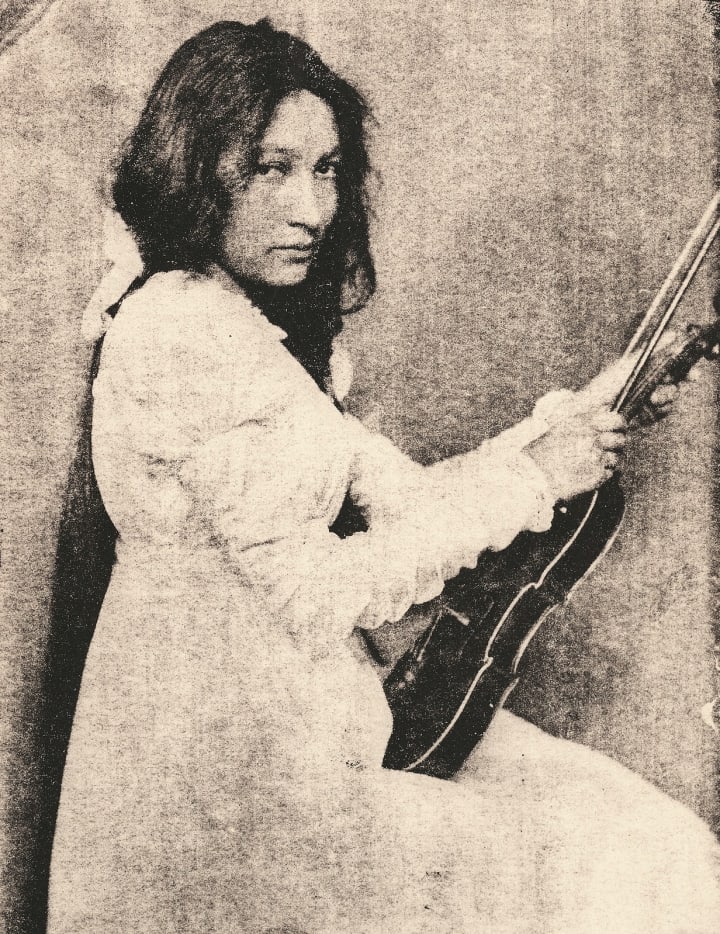

While Zitkála-Šá’s literary work has received considerable attention, her contributions as a musician and composer are often overlooked. Trained in Western classical music, she used this skill to create works that celebrated Native American themes and spirituality.

One of her most significant achievements was The Sun Dance Opera, composed in collaboration with William F. Hanson in 1913. This opera was among the first of its kind to center on Native American stories, rituals, and music. It dramatized the sacred Sun Dance ceremony of the Plains tribes, portraying indigenous spirituality with dignity and complexity rather than the caricatures common in popular culture.

The Sun Dance Opera was a radical artistic statement in its time, blending Native oral traditions and melodies with Western operatic forms. It challenged dominant cultural assumptions and asserted the validity and sophistication of Native cultures. Unfortunately, like many of her other achievements, the opera was largely neglected by mainstream history and the arts world for decades.

Her musical work reflects a broader pattern in which Native American contributions to art and culture were marginalized or ignored, reinforcing stereotypes and limiting the representation of indigenous peoples to narrow tropes.

Political Advocacy: Fighting for Rights and Sovereignty

Her worBeyond art and literature, Zitkála-Šá was a formidable political activist. She recognized that cultural survival was intimately linked to political rights and sovereignty. Moving to Washington, D.C., she became a vocal advocate for Native American issues at the national level.

In 1926, Zitkála-Šá co-founded the National Council of American Indians (NCAI), one of the first pan-tribal organizations dedicated to defending indigenous rights. The council worked tirelessly to challenge federal policies that threatened Native landholdings and cultural practices and to secure full U.S. citizenship and voting rights for Native Americans.

Her activism was groundbreaking in many ways. At a time when Native Americans faced widespread discrimination, lack of political representation, and legal restrictions, Zitkála-Šá used her eloquence and political savvy to lobby Congress, testify at hearings, and educate the public. She was a pioneering figure who helped lay the groundwork for future Native civil rights movements.

Her work also intersected with broader struggles for women’s rights. As a Native woman leader, she navigated the dual challenges of racism and sexism, carving out a space where Native voices, especially Native women’s voices, could be heard in political discourse.

The Struggles and Erasure of a Native Voice

Despite her extraordinary accomplishments, Zitkála-Šá’s story was largely erased or diminished in mainstream history for much of the 20th century. Several factors contributed to this erasure.

First, her identity as a Native woman who operated within white cultural institutions complicated how she was perceived. She challenged simplistic racial binaries by embodying a complex bicultural identity that unsettled dominant narratives.

Second, her outspoken critiques of assimilation policies and federal Indian policy made her a contentious figure. Rather than being celebrated, her activism often met resistance from both government officials and segments of society invested in maintaining the status quo.

Third, the broader marginalization of Native American contributions to culture, literature, and politics meant that her achievements were often ignored or forgotten in academic and popular histories.

This erasure has had lasting effects. The absence of figures like Zitkála-Šá from history books has perpetuated misunderstandings about Native Americans and obscured the rich diversity of indigenous experiences and leadership.

Rediscovery and Contemporary Legacy

In recent decades, there has been a growing movement to reclaim Zitkála-Šá’s legacy. Scholars have reexamined her writings and activism, bringing her story into the canon of American literature and history. Native communities honor her as a foundational figure in cultural preservation and political advocacy.

Her work has inspired contemporary Native writers, musicians, and activists, who see in her life a model of resilience, creativity, and courageous resistance. Universities now include her writings in curricula exploring Native American history, literature, and women’s studies.

Her musical contributions are being revived in performances of The Sun Dance Opera and other works, restoring her place as a pioneering figure in Native American arts.

Zitkála-Šá’s life teaches us about the complexity of identity and the ongoing struggles for cultural survival. Her story reminds us that history is not fixed but must be continually revisited and expanded to include voices that were silenced or marginalized.

Zitkála-Šá’s story is a testament to the power of storytelling as resistance. Her life bridged worlds torn apart by colonial violence and assimilationist policies. She used literature, music, and political activism to assert the humanity and sovereignty of Native peoples.

By recovering her legacy, we reclaim a piece of history that was lost—one that challenges us to rethink the stories we tell about America and its people. Zitkála-Šá’s song, once nearly silenced, now soars as a powerful symbol of resilience, cultural pride, and the unyielding spirit of a people determined to survive and thrive.

'' Her life invites us to honor all those who were erased from history and to ensure their voices are heard, their stories told, and their truths remembered. "

About the Creator

Kek Viktor

I like the metal music I like the good food and the history...

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.