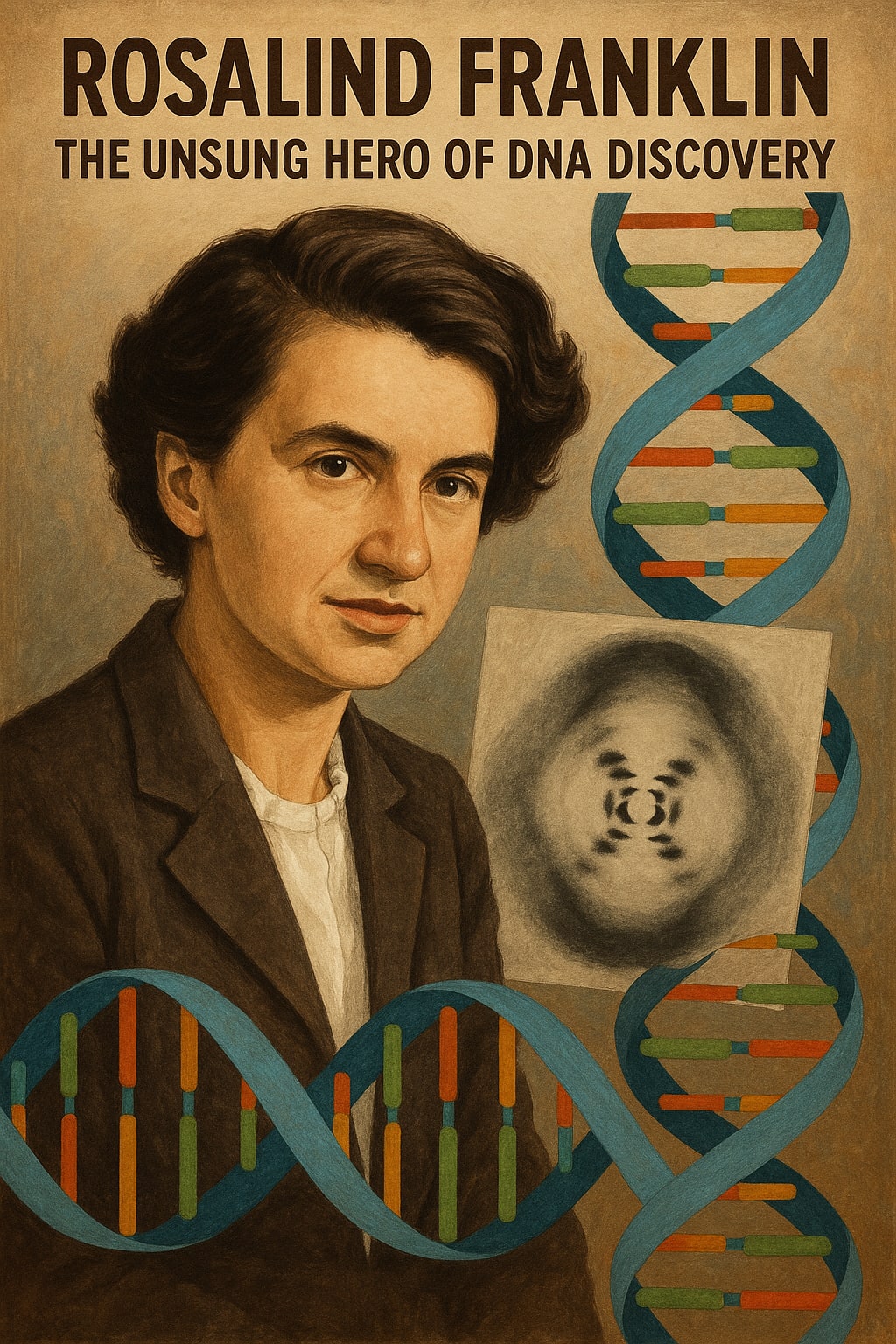

The Unsung Hero of DNA Discovery

A Brilliant Mind Behind the Double Helix Who Changed the Course of Science

In the annals of scientific history, some names are etched in glory, while others, despite immense contributions, remain in the shadows. One such name is Rosalind Franklin, a pioneering chemist and crystallographer whose meticulous work was instrumental in revealing the structure of DNA. Though often overlooked during her lifetime, her legacy now stands as a beacon of scientific excellence, perseverance, and integrity.

Early Life and Education

Rosalind Elsie Franklin was born on July 25, 1920, in Notting Hill, London, into an affluent and intellectual British-Jewish family. Her father, Ellis Franklin, was a banker who valued education deeply, and her mother, Muriel, came from a family of scholars. Encouraged from an early age to pursue knowledge, Rosalind exhibited an exceptional aptitude for math and science.

At the age of 11, she entered St. Paul’s Girls’ School, one of the few schools at the time that taught physics and chemistry to girls. Her academic excellence earned her a scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge, where she studied chemistry from 1938 to 1941. Despite graduating with honors, women were not awarded full degrees at Cambridge until 1948 — a reflection of the gender barriers she would face throughout her career.

The Road to Crystallography

After university, Franklin joined the British Coal Utilisation Research Association, where she researched the micro-structure of carbon and co-authored several papers. This experience sparked her lifelong interest in X-ray crystallography, a technique used to determine the atomic structure of molecules. She pursued a Ph.D. at Cambridge and then moved to Paris in 1947 to work at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l’État under crystallographer Jacques Mering, mastering X-ray diffraction techniques.

The King’s College Chapter and DNA

In 1951, Franklin returned to London to work at King’s College in the Biophysics Unit, led by John Randall. There, she was assigned to investigate DNA. She worked independently and diligently, applying X-ray diffraction to capture images of DNA’s molecular structure. Her colleague, Maurice Wilkins, with whom she had a contentious working relationship, had also been studying DNA. Their rivalry and lack of clear communication often clouded their interactions.

Franklin and her student, Raymond Gosling, captured a photograph that would become legendary in the history of science: Photo 51. This high-resolution X-ray diffraction image of DNA was clear evidence that the molecule had a helical structure.

Unbeknownst to Franklin, this image and her data were shown to James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge University by Wilkins, without her permission. Watson and Crick used her findings — particularly the dimensions and structure of the helix revealed by Photo 51 — to build their famous double helix model of DNA, published in Nature in 1953. While their model changed biology forever, Franklin’s name was only briefly mentioned in a footnote.

The Move to Birkbeck and Virus Research

Disillusioned by the environment at King’s College, Franklin moved to Birkbeck College in 1953, joining the lab of John Desmond Bernal, a brilliant and supportive figure. There, she turned her attention to the structure of viruses, including the tobacco mosaic virus and polio virus. Her work laid the foundation for structural virology and contributed to our understanding of how viruses function.

Franklin’s research at Birkbeck was groundbreaking. She published over 17 papers in five years and collaborated with several scientists who would later earn recognition in their own right. Despite the professional setbacks she had faced earlier, her brilliance continued to shine.

Personal Life and Character

Rosalind Franklin was known for her determination, precision, and independence. She could be reserved and serious but was deeply loyal to her close friends. Outside of the lab, she enjoyed hiking, traveling, and photography. She never married, dedicating her life to scientific inquiry.

While often portrayed as a victim of scientific rivalry, Franklin never sought sympathy or recognition. She valued the integrity of the scientific process above personal gain. In many ways, she was ahead of her time — a woman navigating a male-dominated field, asserting intellectual authority with quiet strength.

Illness and Untimely Death

In 1956, at the age of 36, Franklin was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, likely exacerbated by her prolonged exposure to X-ray radiation. Despite her illness, she continued to work, traveling, writing papers, and mentoring students. She succumbed to the disease on April 16, 1958, at the age of 37.

Posthumous Recognition

Franklin’s premature death meant she was not eligible for the Nobel Prize, which cannot be awarded posthumously. In 1962, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins for the discovery of DNA’s structure. Many scientists and historians have since debated the ethical implications of her exclusion.

Over time, recognition of Franklin’s role has grown. Books, documentaries, plays, and even postage stamps have celebrated her life. Institutions like the Rosalind Franklin Institute in the UK honor her legacy, and her contributions are now taught in science curricula around the world.

Legacy

Rosalind Franklin’s story is one of brilliance, resilience, and unrecognized genius. She changed the face of biology with her precise and powerful science. Though denied the limelight during her life, her legacy endures as a symbol of intellectual courage and the often-unacknowledged contributions of women in science.

Her life reminds us that science is a collaborative endeavor — and that integrity and dedication, even when not immediately celebrated, can leave an indelible mark on human progress.

⸻

“Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.”

About the Creator

Irshad Abbasi

"Studying is the best cure for sorrow and grief." shirazi

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.