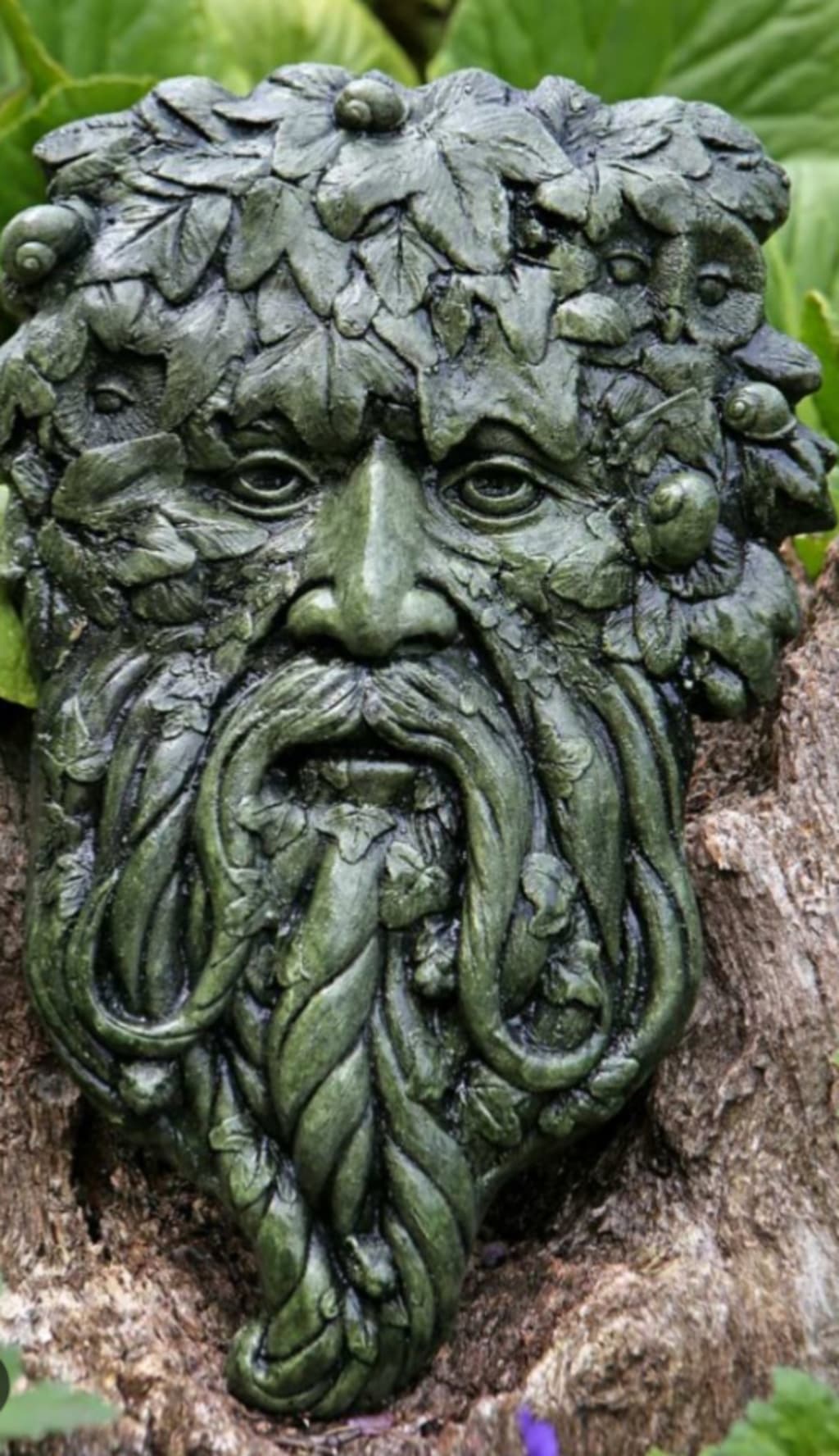

Thousands of years ago Celts in Europe worshipped trees, and the spirit of the tree was depicted as the Greenman, as described below.

| Sacred WiccaThe Green Man is a mysterious, leafy face appearing in art and architecture, symbolizing nature's rebirth, a wild spirit, or the male aspect of Earth, prevalent in medieval churches but with roots in older folklore, representing cycles of growth and found in pagan traditions as a consort to the Earth Mother Goddess. He's depicted as a man with leaves for hair or vines sprouting from his mouth, known technically as a "foliate head," representing a link between humanity and the natural world, often appearing as a festive figure in parades or as a powerful symbol in modern neo-Paganism.

Tree worship has come down to us as superstition - “knock on wood“ after you say something and you want to ensure it will come true, is one example.

Key Characteristics & Meanings

Appearance: A human face intertwined with or made of foliage, often with leaves for hair or vines emerging from the mouth or eyes.

Symbolism: Represents the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, especially the spring awakening of nature.

Origins: Found in classical antiquity but became widespread in medieval churches (11th century onwards) as "foliate heads" or "disgorging heads".

Folklore: Linked to "wild men" in processions, festivals, and myths, a figure of nature and fertility, sometimes associated with alcohol.

The Greenman is definitely of pagan origin.

Contexts

Architecture: A popular motif in churches, often carved into capitals, bosses, and other stonework, appearing alongside Christian imagery.

Paganism/Wicca: A male counterpart to the Earth Goddess (Gaia), representing fertility, wildness, and the spirit of the forest, according to Helene Knott.

Modern Culture: A popular figure in art and literature.

The Green Man, also known as a foliate head, is a motif in architecture and art, of a face made of, or completely surrounded by, foliage, which normally spreads out from the centre of the face. Apart from a purely decorative function, the Green Man is primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the cycle of new growth that occurs every spring.

The Green Man motif has many variations. Branches or vines may sprout from the mouth, nostrils, or other parts of the face, and these shoots may bear flowers or fruit. In the Czech Republic, the Greenman is shown eating red berries or cranberries. Found in many cultures from many ages around the world, the Green Man is often related to natural vegetation deities. Often used as decorative architectural ornaments, where they are a form of mascaron or ornamental head, Green Men are frequently found in architectural sculpture on both secular and ecclesiastical buildings in the Western tradition. In churches in England, the image was used to illustrate a popular sermon describing the mystical origins of the cross of Jesus.

"Green Man" type foliate heads first appeared in England during the early 12th century deriving from those of France, and were especially popular in the Gothic architecture of the 13th to 15th centuries. The idea that the Green Man motif represents a pagan mythological figure.

Usually referred to in art history as foliate heads or foliate masks, representations of the Green Man take many forms, but most just show a "mask" or frontal depiction of a face, which in architecture is usually in relief. The simplest depict a man's face peering out of dense foliage. Some may have leaves for hair, perhaps with a leafy beard. Often leaves or leafy shoots are shown growing from his open mouth and sometimes even from the nose and eyes as well. In the most abstract examples, the carving at first glance appears to be merely stylised foliage, with the facial element only becoming apparent on closer examination. The face is almost always male; green women are rare. Lady Raglan coined the term "Green Man" for this type of architectural feature in her 1939 article The Green Man in Church Architecture in The Folklore Journal. It is thought that her interest stemmed from carvings at St. Jerome's Church in Llangwm, Monmouthshire.

The Green Man appears in many forms, with the three most common types categorized as:

the Foliate Head: completely covered in green leaves

the Disgorging Head: spews vegetation from its mouth

the Bloodsucker Head: sprouts vegetation from all facial orifices (e.g. tear ducts, nostrils, mouth, and ears)

In terms of formalism, art historians see a connection with the masks in Iron Age Celtic art, where faces emerge from stylized vegetal ornament in the "Plastic style" metalwork of La Tène art. Since there are so few survivals, and almost none in wood, the lack of a continuous series of examples is not a fatal objection to such a continuity.

The Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore suggests that they ultimately have their origins in late Roman art from leaf masks used to represent gods and mythological figures. A character superficially similar to the Green Man, in the form of a partly foliate mask surrounded by Bacchic figures, appears at the centre of the 4th-century silver salver in the Mildenhall Treasure, found at a Roman villa site in Suffolk, England; the mask is generally agreed to represent Neptune or Oceanus and the foliation is of seaweed.

In his lectures at Gresham College, historian and professor Ronald Hutton traces the green man to India, stating "the component parts of Lady Raglan's construct of the Green Man were dismantled.The medieval foliate heads were studied by Kathleen Basford in 1978 and Mercia MacDermott in 2003. They were revealed to have been a motif originally developed in India, which travelled through the medieval Arab empire to Christian Europe. There it became a decoration for monks’ manuscripts, from which it spread to churches."

A late 4th-century example of a Green Man disgorging vegetation from his mouth is at St. Abre, in St. Hilaire-le-grand, France. 11th century Romanesque Templar churches in Jerusalem have Romanesque foliate heads. Mike Harding tentatively suggested that the symbol may have originated in Asia Minor and been brought to Europe by travelling stone carvers. The tradition of the Green Man carved into Christian churches is found across Europe, including examples such as the Seven Green Men of Nicosia carved into the facade of the thirteenth century St Nicholas Church in Cyprus. The motif fitted very easily into the developing use of vegetal architectural sculpture in Romanesque and Gothic architecture in Europe. Later foliate heads in churches may have reflected the legends around Seth, the son of Adam, according to which he plants seeds in his dead father's mouth as he lies in his grave. The tree that grew from them became the tree of the True Cross of the crucifixion. This tale was in The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, a very popular thirteenth century compilation of Christian religious stories, from which the subjects of church sermons were often taken, especially after 1483, when William Caxton printed an English translation of the Golden Legend.

According to the Christian author Stephen Miller, author of "The Green Man in Medieval England: Christian Shoots from Pagan Roots" (2022),”It is a Christian/Judaic-derived motif relating to the legends and medieval hagiographies of the Quest of Seth – the three twigs/seeds/kernels planted below the tongue of post-fall Adam by his son Seth (provided by the angel of mercy responsible for guarding Eden) shoot forth, bringing new life to humankind". This notion was first proposed by James Coulter (2006).

We commissioned this pewter button in the Czech Republic exclusively for us at Wildthingsbeads.

This glass button was commissioned by us in the Czech Republic.

Glass buttons handpainted by an artist we found in Czech Republic. She is the only artist there who does this. She was trained by her father.

This Greenman cabochon was carved in Bali, Indonesia exclusively for us at Wildthingsbeads.

the Renaissance onward, elaborate variations on the Green Man theme, often with animal heads rather than human faces, appear in many media other than carvings (including manuscripts, metalwork, bookplates, and stained glass). They seem to have been used for purely decorative effect rather than reflecting any deeply held belief.

Modern times

In Britain, the image of the Green Man enjoyed a revival in the 19th century, becoming popular with architects during the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts era, when it appeared as a decorative motif in and on many buildings, both religious and secular. American architects took up the motif around the same time. Many variations can be found in Neo-Gothic Victorian architecture. He was popular amongst Australian stonemasons and can be found on many secular and sacred buildings, including an example on Broadway, Sydney. In 1887 a Swiss engraver, Numa Guyot, created a bookplate depicting a Green Man in exquisite detail.

In April 2023, a Green Man's head was depicted on the invitation for the Coronation of Charles III and Camilla, designed by heraldic artist and manuscript illuminator Andrew Jamieson. According to the official royal website: "Central to the design is the motif of the Green Man, an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth, to celebrate the new reign. The shape of the Green Man, crowned in natural foliage, is formed of leaves of oak, ivy, and hawthorn, and the emblematic flowers of the United Kingdom." which alluded to "the nature worshipper in King Charles" but polarized the public. Indeed, as the medieval art historian Cassandra Harrington pointed out, although vegetal figures were abundant throughout the medieval and early modern period, the foliate head motif is not ‘an ancient figure from British folklore’, as the Royal Household has proclaimed, but a European.

The Green Man is a term with a variety of connotations in folklore and related fields.

During the early modern period in England, and sometimes elsewhere, the figure of a man dressed in a foliage costume, and usually carrying a club, was a variant of the broader European motif of the Wild Man (also known as wild man of the woods, or woodwose). By at least the 16th century the term "green man" was used in England for a man who was covered in leaves, foliage including moss as part of a pageant, parade or ritual, who often was the whiffler (a person who clears a path or space through the crowd for a parade or performance). From the 17th century such figures were used for the names of pubs, and painted on their signs.

In 1939, Julia Somerset, Lady Raglan, wrote an article in the journal Folklore that connected the foliate head artistic motif of medieval church architecture (which she also called the "Green Man") with other "green"-related concepts, such as the "Green Man" pubs, the Jack in the Green folk custom and May Day celebrations.[2She proposed that the "Green Man" represented a pagan fertility figure. The idea has been contested by other folklorists, who assert that Lady Raglan had no evidence that the foliate head motif or other concepts she associated with it were pagan in nature.

Lady Raglan's idea of the "Green Man" was adopted from the 1960s onward by the New Age and Neopagan movements, and some authors have considered it to represent a Jungian archetype. The nature of the Green Man as a mythological figure has been described as "20th-century folklore".

when Europeans came to America as settlers they brought the Greenman with them, but it became the boogeyman, to scare small children into being good.

literature.

The Green Man has been asserted by some authors to be a recurring theme in literature. Leo Braudy, in his 2016 book, Haunted: On Ghosts, Witches, Vampires, Zombies, and Other Monsters of the Natural and Supernatural Worlds asserts that the figures of Robin Hood and Peter Pan are associated with a Green Man, as is that of the Green Knight in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Green Knight in this poem serves as both a monster antagonist and as mentor to Sir Gawain, belonging to a pre-Christian world which seems antagonistic to, but is in the end harmonious with, the Christian one.[6] In Thomas Nashe's masque Summer's Last Will and Testament (1592, printed 1600), the character commenting upon the action remarks, after the exit of "Satyrs and wood-Nymphs", "The rest of the green men have reasonable voices .

During the post-war era literary scholars interpreted the Green Knight as being a literary representation of Lady Raglan's Green Man as described in her article "The Green Man in Church Architecture", published in Folklore journal of March 1939. This association ultimately helped consolidate the belief that the Green Man was a genuine, Medieval folkloric, figure. Raglan's idea that the Green Man is a mythological figure has been described as "bunk", with other folklorists arguing that it is simply an architectural motif.

In the final years of the 20th century and earliest of the 21st, the appearance of the Green Man proliferated in children's literature. Examples of such novels in which the Green Man is a central character are Bel Mooney's 1997 works The Green Man and Joining the Rainbow, Jane Gardam's 1998 The Green Man, and Geraldine McCaughrean's 1998 The Stones are Hatching. Within many of these depictions, the Green Man figure absorbs and supplants a variety of other wild men and gods, in particular those which are associated with a seasonal death and rebirth. The Rotherweird Trilogy by Andrew Caldecott draws heavily on the concept of the Green Man, embodied by the gardener Hayman Salt who is transformed into the Green Man at the climax of the first book.

The Green Man is an integral character in Max Porter's novel Lanny, which was longlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize. The Green Men (including a suffragist irritated by the name) and their powers figure significantly in K. J. Charles's novel The Spectred Isle (2017), which was nominated for a RITA Award.

The character Uncle Mike in the Mercy Thompson series by Patricia Briggs is referred to as Green Man by the Welsh character Samuel Cornick in book 3.

Sculpture

The Green Man image made a resurgence in modern times, with artists from around the world interweaving the imagery into various modes of work. English artist Paul Sivell created the Whitefield Green Man, a wood carving in a dead section of a living oak tree; David Eveleigh, an English garden designer created the Penpont Green Man Millennium Maze, in Powys, Wales ( as of 2006 the largest depiction of a Green Man image in the world); Zambian sculptor Toin Adams created the 12m-tall Green Man in Birmingham, UK as of 2006 the largest free-standing sculpture of the Green Man in the world; and sculptor M. J. Anderson created the marble sculpture titled Green Man as Original Coastal Aboriginal Man of All Time from Whence the Bush and All of Nature Sprouts from his Fingers. Others include Jane Brideson, Australian artist Marjorie Bussey, American artist Monica Richards, and English fantasy artist Peter Pracownik, whose artwork has appeared in several media, including full-body tattoos.

American artist Rob Juszak took the theme of the Green Man as Earth's spiritual protector and turned it into a vision of the Green Man cradling the planet; Dorothy Bowen created a kimono silk painting, titled Greenwoman, as an expression of the feminine aspect of the legend.

so now you know everything about the Greenman.

About the Creator

Guy lynn

born and raised in Southern Rhodesia, a British colony in Southern CentralAfrica.I lived in South Africa during the 1970’s, on the south coast,Natal .Emigrated to the U.S.A. In 1980, specifically The San Francisco Bay Area, California.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.