The Sickle and the Soil

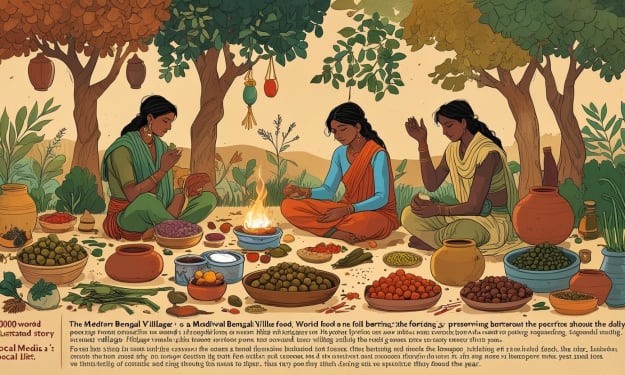

A Year of Food in a Medieval Bengali Village

A Year of Food in a Medieval Bengali Village

Imagine Nadiapur, a small village hugging the curves of the Surma River in medieval Bengal, where life moves with the sun’s arc and the river’s moods. I’m Tapan, a farmer’s son, sixteen summers old, with hands rough from cutting rice and eyes sharp from scanning the forest for greens. Our story isn’t one of warriors or palaces, but of meals scraped from the earth, shared under straw roofs, and carried in the heart. Let me walk you through a year in Nadiapur—our food, our toils, our quiet triumphs—as if we’re gathered by a fire, a clay plate of steaming bhaat between us, the night alive with stories. This is for Vocal Media, a tale to make you feel the weight of a sickle and the warmth of a shared meal.

Spring: The Seeds of Survival

Spring wakes Nadiapur with a soft glow. The river glints, and the paddies stir with new rice shoots. My father, Baba, sharpens his sickle, while Ma sorts seeds saved from last year’s harvest, her fingers quick and sure. Mornings begin with bhaat—rice boiled in a blackened pot, eaten with shak, the wild greens my sister Mita and I gather at dawn. We slip into the forest, baskets bumping our hips, searching for pui leaves or kathal seeds, their nutty crunch a prize when roasted. Ma taught us the land’s secrets: which greens heal, which sicken. “Never touch the red-stemmed ones, Tapan,” she’d warn, her voice cutting through the morning mist.

Food is plain but vital. Midday might bring dal—lentils simmered with a single chili from our garden. If the river’s kind, we have fish—koi or shingi—caught in nets I help Baba mend. Meat is a dream; only the zamindar’s hunters taste deer or boar. Instead, we barter: Baba’s rice for a neighbor’s kochur loti, or Ma’s woven mats for a handful of amra fruit. Preservation starts early. We dry fish in the sun, their bodies stiffening into silver strips, and store rice in clay pots sealed with mud. Mita and I help Ma pickle green mangoes, the jars tucked in a cool corner of our hut.

Evenings are for sharing. We sit on the mud floor, a single plate of rice and shak bhaji passed between us. Baba tells of the river’s spirit, said to guard the fish we catch. The food is simple, but the stories—of floods or far-off kings—make it a feast. Every bite is a thread tying us to Nadiapur’s soil.

Summer: The Sun’s Hard Bargain

Summer scorches Nadiapur. The river dwindles, and the paddies crack like old skin. Hunger creeps in, a quiet guest. Breakfast is chira—flattened rice—softened in water, maybe with a few ber fruits Mita finds. Foraging is a chore under the blazing sun. We trek deeper into the forest, dodging thorns, to dig for yam or pluck thankuni leaves for a bitter salad. The women lead, their laughter a shield against the heat. Aunt Rekha knows every root, her hands pulling kolmi shak from marshy patches, her stories of forest spirits keeping us brave.

Midday meals are thin—a handful of rice with watery dal or boiled greens. Fish are rare; the river’s too shallow for nets. Sometimes, a neighbor shares a chingri prawn curry, and we repay them with Baba’s rice or my help fixing their fence. Barter is our lifeblood. Once, we traded a sack of rice for a goat kid, named Kali, whose milk became our treasure. Evenings bring the village together around a shared fire. Ma fries kumro flowers, their crisp edges a small joy, or boils keshur—water chestnuts—when we’re lucky. We eat slowly, listening to old man Gopal’s tales of a drought that forced the village to eat roots and prayers.

Summer demands care. We ration rice, mix it with greens, and check our stores daily. The dried fish shrink, but Kali’s milk keeps Mita strong. One night, under a starlit sky, Baba spoke of his father, who saw a trader from Delhi, his cart heavy with spices we’d never taste. The story lingered, like the taste of chira on our tongues.

Monsoon: The River’s Dance

The rains flood Nadiapur, turning fields to lakes. The Surma River swells, bringing fish—pabda, magur, slippery eels. Mita and I wade in, giggling as we set traps, the water lapping our knees. A good catch means a feast: fish curry with green tamarind, shared in a neighbor’s dry hut, the rain pounding outside. But the monsoon is fickle. One year, it drowned our paddy, leaving us with soggy rice and kochur loti stems. We ate them boiled, their starchy bite a grim comfort.

Foraging halts; the forest is mud. Instead, we gather shapla lilies from the flooded fields, their roots chewy and filling. Ma makes soup with whatever greens remain, and we sip it, warming our hands on clay bowls. Preservation is urgent. We dry fish during brief sunny spells, and Aunt Rekha pickles amra fruits, their sour tang a promise of better days. Baba’s rice is traded for salt—a rare prize—and we sprinkle it into our curries, tasting a world beyond Nadiapur.

Evenings are for stories in the headman’s hut, safe from the floods. We share a pot of rice and fish, the steam rising like a prayer. The men talk of tax collectors, their swords glinting in the rain. The women whisper of the river goddess, pleased by our offerings of rice. Each meal strengthens us, a vow to outlast the storm.

Winter: The Harvest’s Embrace

Winter is Nadiapur’s gift. The fields dry, and the rice sways golden. We harvest together, singing of the earth’s kindness. The first meal after is a joy: rice piled high, dal rich with ghee from Kali’s milk, and a fish curry with fresh dhone pata. We eat on the ground, the air sharp, our laughter louder than the river’s hum.

Foraging is easy now. The forest offers mushrooms and ber fruits, and Mita and I race to fill our baskets. Barter thrives—Baba’s rice for yams, Ma’s pithe for jaggery. At poush parbon, we steam rice cakes with coconut, the fires lighting up the night. The women sing, their voices weaving through the smoke, while Baba tells of a Mughal boat he saw as a boy, its sails like wings. Winter meals are generous but measured. We store rice in pots, dry fish for the next lean season, and bury roots in cool earth. Every bite feels like a debt repaid.

The Soul of Nadiapur

Nadiapur’s story is no epic, but it’s ours. Our food—rice, greens, fish, roots—is the land’s pulse, shaped by our sweat. Foraging is our craft, barter our strength, preservation our hope. Each meal is a tale, each shared plate a bond. As I tell this by the fire, the warmth of bhaat in my hands, I feel Nadiapur’s soul: not in glory, but in the quiet work of feeding each other. That’s our truth, carried on the river’s breath.

About the Creator

Shohel Rana

As a professional article writer for Vocal Media, I craft engaging, high-quality content tailored to diverse audiences. My expertise ensures well-researched, compelling articles that inform, inspire, and captivate readers effectively.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.