The Real-Life Captain Kirk

An exciting new bestseller brings fresh life to the man who inspired the most famous line on Star Trek

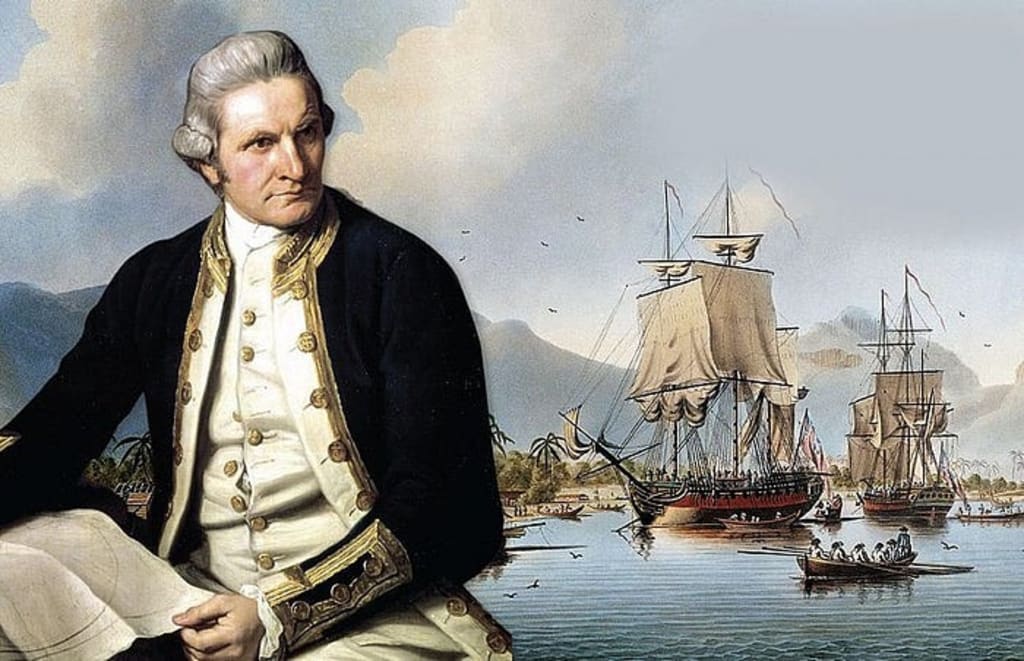

Poor Captain Cook. Some people remember him only as an inspiration for Captain James Kirk of the Starship Enterprise.

Hampton Sides shows how much they're missing in his latest book of popular history, The Wide Wide Sea. His book brings more drama to the story of the British explorer's final voyage than you'll find in — dare I say it? — some episodes of Star Trek.

James Cook has been slaughtered twice. First he was slain in Hawaii after abducting a native king he hoped to exchange for a boat islanders had stolen. More recently, assaults on his reputation have led to the toppling of statues and the vandalizing of monuments to his achievements.

Sides brings Cook to life for a postcolonial generation that requires more complexity than existed in the swashbuckling maritime adventures of yesteryear.

A victim of his own hubris

Sides' new book is a bestselling page-turner in the spirit of David Grann's The Wager and Candice Millard's The River of Doubt. Its appeal lies above all in good storytelling, not in stumping for radical new theories or keeping alive myths of discovery and conquest. It's a welcome change from the cascade of recent histories that reek of special pleading as they aim to do justice to people or groups slighted in the past.

Sides neither deifies nor demonizes Cook. He casts him rather as a man who was a stellar naval officer until hubris set in and his judgment faltered on his third and final trip around the world. His Cook is fearless mariner, a brilliant cartographer, and a Yorkshireman whose views of Indigenous people were, for his time and place, enlightened.

Cook was already famous and when he set sail from Plymouth on the Resolution on July 12, 1776, along with William Bligh, who would later provoke the famous mutiny on the HMS Bounty. He had two assignments from the king, who wasn't too distracted by the turmoil in the colonies to see the importance of Cook's work.

An Indigenous passenger on the ship

Cook's main task was to find a Pacific route to the Northwest Passage by sailing eastward around the Cape of Good Hope and up the west coast of America after other explorers had failed to find a transcontinental waterway via the Atlantic. His second job was to transport to Tahiti an Indigenous man known as Mai (or Omai) who had come to England seeking guns he could use to avenge the deaths of relatives and who wanted to return home.

If it sounds farfetched that George III would authorize a stop in Polynesia for one passenger, it's a sign of Sides' narrative skill that he makes this idea seem credible. In The Wide Wide Sea, only Cook holds more interest than Mai, whose life Sides casts as a poignant allegory of first contact and the unintended consequences of colonialism.

In one of many tragicomic episodes centered on him, Mai had a full suit of armor made for himself in London, hoping it would dazzle his compatriots in Polynesia. He instead found them terrified by the suit and by one of the guns he had traveled thousands of miles to obtain.

Even with his unusual passenger, Cook was so enthusiastic about the trip, he gave up a government sinecure conferred on him as a reward for his earlier derring-do.

Did sciatica change him?

But he had changed as a captain in ways that unsettled his shipmates. In his late 40s, Cook had lost some of his much-admired equanimity, perhaps because of his age, sciatica, or a parasitic infection from bad fish. He judgment was slipping. He took needless risks and flogged his crew for minor infractions, such as drunkenness.

His failings caught up with him after more than two years at sea. In the Arctic Ocean, he ran into a dangerous ice pack that stretched for hundreds of miles and could have trapped his ships. Instead of wisely heading back to England, he made the calamitous decision to overwinter in Hawaii and try again in the spring.

In the islands, native Hawaiians stole a cutter Cook needed for his return to the Arctic. He abducted a king, hoping to exchange him for the boat.

A war erupted, and Cook was fatally clubbed and stabbed with a dagger possibly made from a swordfish bill. It was an inglorious end for a man who wanted to go "farther than any man has been before me," a line adapted by the Star Trek franchise as "where no man has gone before" (and later as the gender neutral "where no one has gone before").

His crew beat a dreaded disease

Sides is no apologist for Cook's missteps. Yet the explorer emerges as undeserving of all the ignominy heaped on him by foes who in recent years have splattered a monument to him with blood-red paint.

Among his underappreciated achievements was beating the mariners' scourge, scurvy. In his day, scurvy might kill off half the crew on any long expedition.

That a vitamin C deficiency caused scurvy wasn't established until the 1930s. But a Scottish surgeon had shown that the disease could be treated with citrus fruit.

Cook built on the Scot's idea by insisting that his men eat fresh fruits and vegetables whenever possible. He also kept aboard the Resolution a type of thickened lemon juice and an orange syrup. An earlier voyage had lasted three years, "but not a single one of his men died of the disease — or even, it seems, developed advanced symptoms," Sides writes.

Sides also suggests that, wherever he went, Cook treated Indigenous people with a degree of respect unusual for its era. He didn't try to convert them to Christianity or to Anglophile ways. He didn't condemn their cannibalism, human sacrifice, or other practices but viewed them in the context of their ceremonial or other roles.

'We debauch their morals'

Cook also accepted that his own visits had caused harm. He sounded remarkably like modern postcolonialists when he wrote of an encounter with the Maori:

"We debauch their morals," he wrote, "and we introduce among them wants and diseases which they never before knew."

James Boswell, the diarist and biographer, had hoped to join Cook on his third voyage, but his mentor Samuel Johnson dissuaded him.

Johnson had little use for any tales of adventure Boswell might collect on such a trip.

"Who will read them through?" he asked Boswell. "There is little entertainment in such books."

Johnson, who was right about so much, was wrong here. There is plenty of entertainment — and more — in The Wide Wide Sea.

@janiceharayda is an award-winning critic and journalist who has been the book critic for a large U.S. newspaper and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle. Her reviews and other articles have appeared in many major media, including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Newsweek, and Salon. Jan also writes about books, the media, and more at Jansplaining, her free Substack newsletter.

About the Creator

General gyan

"General Gyan shares relationship tips, AI insights, and amazing facts—bringing you knowledge that’s smart, fun, and inspiring for curious minds everywhere."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.