The Man Who Mailed Himself to Freedom: The Astonishing Journey of Henry “Box” Brown

A true story of courage, desperation, and the unbreakable human spirit that defied slavery

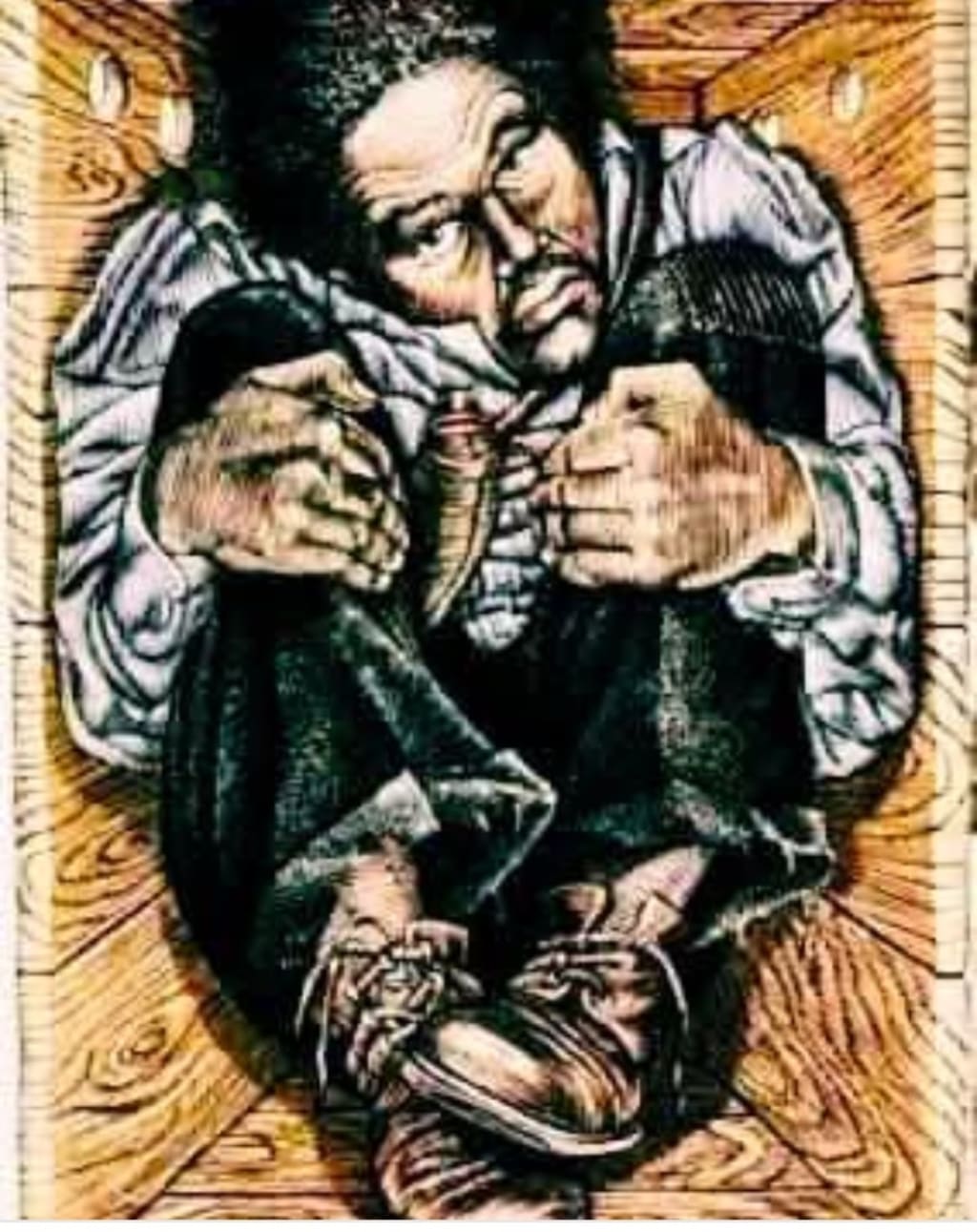

In the long, painful history of slavery in America, many stories of courage were buried, forgotten, or overshadowed by the brutality of the era. Yet among these countless untold stories, one stands out not only for its daring but for its pure, imaginative brilliance. It is the unforgettable tale of Henry “Box” Brown, the man who shipped himself across states in a wooden crate to claim his freedom.

Henry Brown was born into slavery in Louisa County, Virginia, in 1815. Like countless enslaved people, he grew up under the control of others—his time, his labor, even his family were possessions owned by slaveholders. Still, Henry carried a spark within him: a quiet refusal to let life break his spirit. He worked in a tobacco factory in Richmond, forced to spend his days inhaling dust, sweating under harsh conditions, and surrendering his wages to his enslavers.

Despite everything, Henry tried to create a life of love amidst suffering. He married an enslaved woman named Nancy, and together they had three children. However, as slavery often did, it shattered what little happiness Henry could build. One morning in 1848, Henry came home to an unthinkable tragedy—his wife and children had been sold to another owner, taken away without warning, carried far from his reach. In that moment, Henry felt something in his heart collapse. He later wrote that seeing his family dragged away was like having “the cold hand of death” laid upon him.

Grief can crush a man—or it can push him to find a new path. Henry’s path became a daring, dangerous plan few would even dare to imagine.

He decided to mail himself to freedom.

The idea came to him as a sudden spark—a literal “deliverance” through the U.S. postal system. With the help of two abolitionists, James C. A. Smith and Samuel A. Smith (no relation), Henry planned the most extraordinary escape attempt in history. The plan was simple yet nearly impossible: Henry would climb into a wooden box, have himself sealed shut, and then shipped from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—where slavery had been abolished.

A free life lay inside a box not much larger than a coffin.

The box measured 3 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 2.5 feet deep. On the morning of March 29, 1849, Henry climbed inside with nothing but a container of biscuits and a small bladder of water. The box was labeled with chilling practicality:

“This side up with care.”

Henry could only hope that someone would read—and follow—it.

But fate is rarely so kind.

The box journeyed 27 hours through wagons, trains, and finally a steamboat. At times, Henry was flipped upside down, forced to endure the crushing pain of blood rushing to his head. He stayed silent even when the agony was unbearable. At one point, he could feel his eyes swelling so badly he feared they would burst from their sockets. Yet he held on.

He later said, “I felt my brain was about to burst, but I knew one word—just one cry—and I would be discovered.”

Henry remained still, like a dead man inside a wooden coffin traveling toward life.

Finally, on March 30, the box arrived at the office of the Philadelphia abolitionist group. A small group of antislavery activists gathered around it. They tapped the box. They whispered.

And then they asked, “Are you all right inside?”

From within the crate came the most remarkable sound—Henry’s voice answering, “All right!”

When they pried open the lid, Henry emerged like a reborn man, blinking against the light. The first thing he did was stand up, straighten himself, and recite a hymn of praise:

“I waited patiently for the Lord, and He heard my prayer.”

Henry Brown had arrived in freedom.

His story spread like wildfire across the North. Newspapers celebrated him. Abolitionists invited him to speak. He earned the nickname “Henry Box Brown,” which he carried proudly for the rest of his life. He even turned his escape into a stage performance, reenacting the moment he emerged from the box—a symbolic act of hope for enslaved people everywhere.

But Henry’s safety in America was short-lived. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made even free states dangerous for escaped slaves, so Henry fled to England. There, he spent years speaking, performing, and sharing the story of his astonishing escape—using his voice as a weapon against injustice.

Henry Brown eventually returned to the United States after the Civil War, living out his later years as a free man—something he fought harder for than most people could ever imagine.

His journey was not merely a physical escape. It was a declaration of human dignity, a reminder that freedom is not just a right, but a yearning so powerful it can inspire a man to climb into a wooden box and trust the world to carry him toward hope.

Henry “Box” Brown’s story remains one of the most daring acts of self-liberation ever recorded—a testament to courage, imagination, and the unstoppable determination of a man who refused to remain chained.

About the Creator

Hasbanullah

I write to awaken hearts, honor untold stories, and give voice to silence. From truth to fiction, every word I share is a step toward deeper connection. Welcome to my world of meaningful storytelling.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.