The London Underground Has Secrets You Wouldn't Expect

Secrets Beneath the Streets of London

Beneath the bustling streets of one of the world’s most famous cities lies a vast and complex labyrinth: the London Underground. Known to millions simply as “the Tube,” this iconic transport network has served as the lifeblood of London for over 160 years. But behind the hum of trains and the chatter of commuters is a rich tapestry of secrets, innovations, and peculiarities that most people never notice.

Did you know that the London Underground has its own species of mosquito? Yes, you read that right. Known as the Culex pipiens molestus, or the London Underground mosquito, this species evolved entirely separately from its above-ground cousins. It’s adapted to thrive in the dark, subterranean environment and is far more aggressive, biting humans more frequently—probably because non-human prey, like birds, are harder to come by in the underground tunnels.

This mosquito is just one of many extraordinary stories hidden beneath the streets of London. In this in-depth exploration, we’ll delve into the secrets of the London Underground—from its troubled birth during the Victorian era to its modern innovations and its vital role during both World Wars. As you journey through the history of this remarkable network, you’ll discover that the London Underground is much more than just a way to get from point A to point B. It’s a living museum of human ingenuity and perseverance, a system that has shaped not only London but also the way we think about urban transportation around the world.

The Birth of the London Underground: An Idea Ahead of Its Time

In the mid-19th century, London was the beating heart of the world’s largest empire. As the city grew, so did its problems—particularly congestion. The streets were choked with pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages, and carts. By the 1860s, London’s population had skyrocketed to 3 million, far too many for its narrow, medieval streets to accommodate.

While traffic jams may seem like a modern problem, they were even worse during Victorian times. The streets were overrun, and getting from one part of the city to another was a slow and dirty ordeal. Horse manure, mud, and constant gridlock plagued the city, making it clear that something needed to change.

This is where Charles Pearson, a solicitor with a vision, entered the picture. Pearson saw the need for a transportation revolution—one that would move people beneath the congested streets of London. He proposed the creation of an underground railway system, which was considered a radical idea at the time. In 1845, Pearson published a pamphlet detailing his vision of an atmospheric railway—a train system powered by compressed air traveling through underground tunnels. While his atmospheric railway never came to fruition, his advocacy set the wheels in motion for the creation of the world’s first underground railway.

Pearson faced significant opposition, with many considering his idea impossible or simply too expensive. However, as congestion worsened, his plan gained support. In 1860, construction began on the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground line, which ran between Paddington and Farringdon Street, covering just under four miles with five intermediate stations. It was a groundbreaking moment in urban transport history.

The Challenges of Building the Underground: Cut-and-Cover

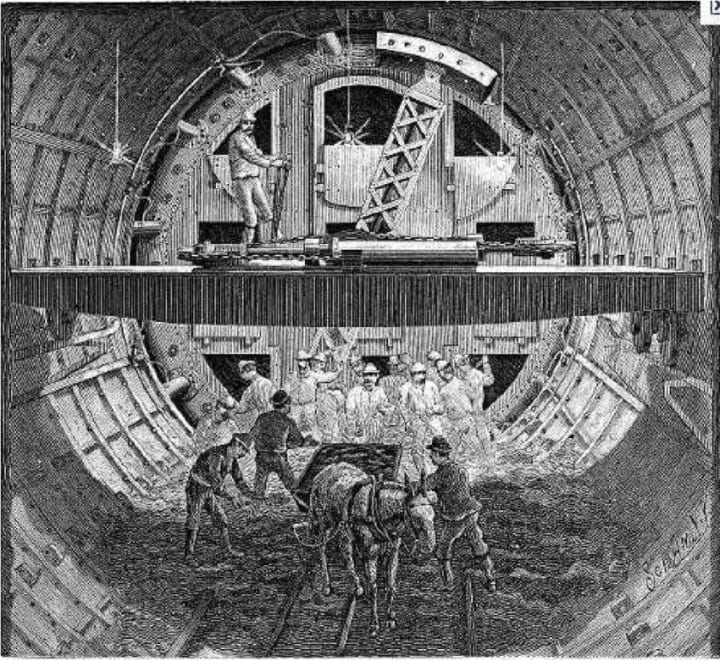

Building the London Underground was no easy feat, especially in the 1860s when modern tunneling machines were non-existent. Instead, engineers used a method called cut-and-cover. This involved digging a trench through the streets, laying down the railway tracks, and then covering the trench with brick arches before restoring the street on top. While effective, it was also incredibly disruptive. Huge sections of London were essentially torn up to make way for the new underground railway.

This method of construction led to public frustration and earned the Metropolitan Line the nickname “The Sewer Line” due to the mess it caused. Despite the disruption, the line was completed, and the first underground railway in the world opened to passengers in 1863. Over 38,000 people rode the Metropolitan Line on its first day, a staggering number for the time. Yet, as novel as the underground was, it faced one major flaw: it was powered by steam locomotives.

The Steam-Powered Underground: A Smoky Problem

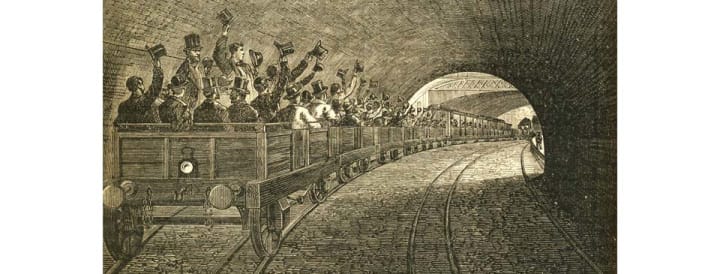

Imagine traveling underground in a smoke-filled tunnel on an open-air train. The early Metropolitan Line trains were powered by steam, meaning thick black smoke filled the tunnels and made the commute anything but pleasant. The carriages themselves were open-air, resembling coal carts more than modern passenger trains, and the conditions were stifling, especially during the summer months.

Unsurprisingly, this deterred many potential riders, especially wealthier commuters who were unwilling to subject themselves to the discomfort of riding in smoke-filled tunnels. Still, the convenience of avoiding the congested streets of London was too great for many to ignore, and over the next six months, the Metropolitan Line carried more than one million passengers.

The success of the first underground line spurred the expansion of the network. New lines, including the District Railway in 1868 and the City and South London Railway in 1890 (the first electric underground railway), were added, helping to alleviate the congestion on the streets above. But the real breakthrough came with the introduction of electric trains, which finally eliminated the need for smoke-belching steam engines in underground tunnels.

Going Deeper: The Greathead Shield and the Expansion of the Underground

As the Underground expanded, new technology allowed for deeper tunneling, avoiding the disruption of cut-and-cover methods. The invention of the Greathead Shield, developed by engineer James Henry Greathead, revolutionized underground construction. This shield allowed workers to excavate deep below the surface, protecting them from cave-ins as they tunneled beneath the city. Workers could manually dig through the earth, and the shield would be pushed forward, creating space for the tunnel. Cast-iron segments were then installed to form the tunnel walls.

This method allowed the construction of deeper lines that wouldn’t disturb the bustling streets of London, paving the way for the growth of the Underground into the sprawling network it is today.

By the early 1900s, the London Underground had become an integral part of life in the city, carrying hundreds of thousands of passengers each day. The expansion also prompted a move toward suburbanization, as more people realized they could live further from the city center and still commute quickly and easily.

The London Underground’s Role During the World Wars

While the London Underground is best known as a transportation system, during the World Wars, it played an unexpected role as a lifeline for the people of London. During World War I, many stations were repurposed as bomb shelters, protecting Londoners from air raids. This practice became even more critical during World War II, when the Underground became a vital refuge during the Blitz.

The London Underground Has Secrets You Wouldn't Expect. You'll definitely enjoy this!

From 1940 to 1941, German bombers relentlessly targeted London, and the Underground offered shelter to around 300,000 people every night. The tunnels became more than just shelters—they were transformed into makeshift homes. Some stations even set up schools and libraries to keep children occupied during the long hours spent underground. Despite the grim circumstances, the Underground became a symbol of resilience and survival for Londoners.

But the Underground wasn’t just a refuge for civilians. It also housed some of Britain’s most valuable artifacts. The British Museum stored its priceless Elgin Marbles in the Underground to protect them from bomb damage during the war.

One of the lesser-known stories of the Underground during the war involved Down Street Station. Closed in 1932 due to low passenger numbers, this station found a new life as a secret wartime bunker. It was used by the Railway Executive Committee to manage Britain’s rail network, and it even served as an operational base for Winston Churchill during the war. Churchill famously hosted dinners in the converted station’s mess hall, serving champagne and caviar to his war cabinet.

Ghost Stations and Hidden Tunnels: The Underground’s Secret Life

Beneath the streets of London lies a labyrinth of disused stations and hidden tunnels, often referred to as ghost stations. Some of these stations have been closed for decades but still retain a sense of mystery and secrecy about their modern-day use.

One such ghost station is Aldwych Station, which was closed in 1994. It has since found new life as a film set, and if you’ve ever seen a movie or TV show featuring the London Underground, there’s a good chance it was filmed on the platform of Aldwych Station.

Other stations, like Down Street and Brompton Road, have been repurposed for military or secret government use. While some of these tunnels are no longer in use, others still serve a purpose, often hidden in plain sight beneath the city.

Mail Rail: The Underground’s Forgotten Postal Service

In addition to carrying passengers, the London Underground once had a secret postal railway system called Mail Rail. Launched in 1927, this specialized railway transported letters and parcels through its own underground tunnels, independent of the main passenger lines. Mail Rail was a critical part of the British postal system for decades, moving millions of letters every day.

Running from Paddington to Whitechapel, Mail Rail featured tiny, unmanned electric trains that whizzed through tunnels just 2 feet wide at a steady pace of 35 mph. At its peak, Mail Rail transported 4 million letters daily. However, as the volume of mail declined and the cost of maintaining the system rose, Mail Rail was closed in 2003.

In 2017, a portion of the Mail Rail network was transformed into a museum, where visitors can now ride the tiny trains and experience a piece of the Underground’s hidden history.

A Modern Marvel: The Underground Today

Over the years, the London Underground has continued to evolve. Modern innovations, like the introduction of the Victoria Line in 1969—the first line to use automatic trains—have made the system faster and more efficient. Today, the Victoria Line is the second-most frequent train service in the world, with just 100 seconds between trains during peak hours, second only to the Moscow Metro.

The London Underground was also a pioneer in contactless payment, introducing the Oyster card in 2003. This smart card system revolutionized fare collection, allowing passengers to tap in and out of the system quickly and efficiently.

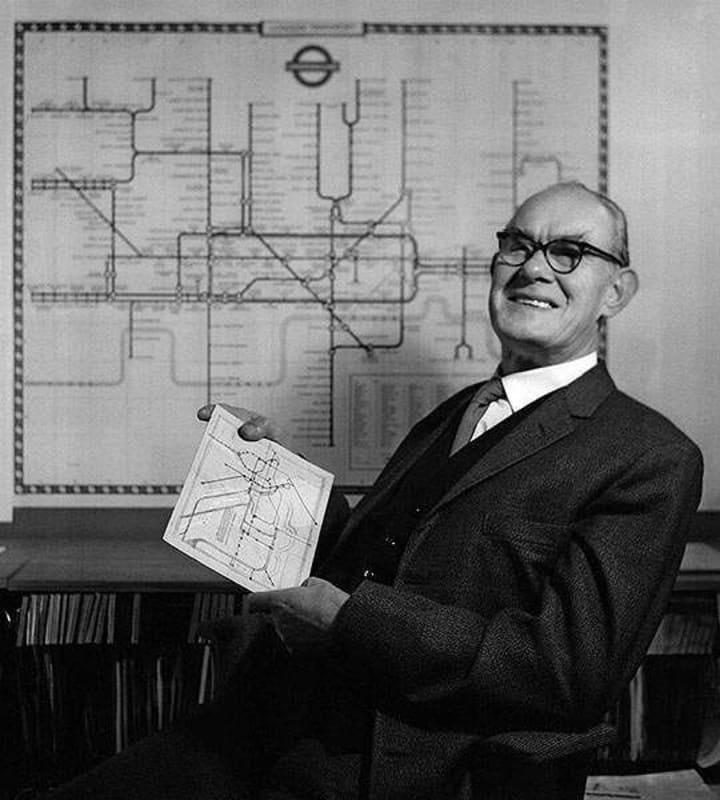

But despite its modern advancements, the London Underground still retains much of its historical charm. Many of the original Leslie Green-designed stations, with their oxblood-red facades and intricate tiling, remain in use today. The Underground map, designed by Harry Beck in 1931, has become an iconic symbol of London, its simplified design copied by metro systems worldwide.

The Cultural Influence of the London Underground

The London Underground is more than just a transportation system; it has become an integral part of British culture. From its distinctive “Mind the Gap” announcement to its portrayal in films, books, and art, the Tube has captured the imagination of people around the world.

Beck’s map, with its bright colors and straight lines, not only made navigating the Underground easier but also became a cultural symbol of London itself. Over 90 years later, his design remains largely unchanged and has influenced transit maps across the globe. It has also inspired merchandise, artwork, and even fashion.

But the Underground is not without its quirks. For instance, many people are surprised to learn that some stations that appear close together on the map, like Covent Garden and Leicester Square, are just 300 meters apart, making it quicker to walk between them than to take the Tube. On the other hand, stations like Canary Wharf and North Greenwich seem close on the map but are actually miles apart, requiring a long walk—or a very short Tube ride.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Subway

The London Underground is a remarkable achievement of engineering and human perseverance. What began as a radical idea to alleviate Victorian traffic jams has grown into a world-famous transport system that moves millions of people every day. Its history is filled with innovation, from steam trains to electric locomotives, from cut-and-cover to deep tunneling, and from manual ticketing to automated fare collection.

Yet, as you step aboard the next train and mind the gap, remember that you’re riding through more than just a subway. Beneath your feet lies a rich history of invention, adaptation, and survival. The Underground isn’t just a mode of transportation—it’s a living, breathing museum of London’s past, present, and future.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.