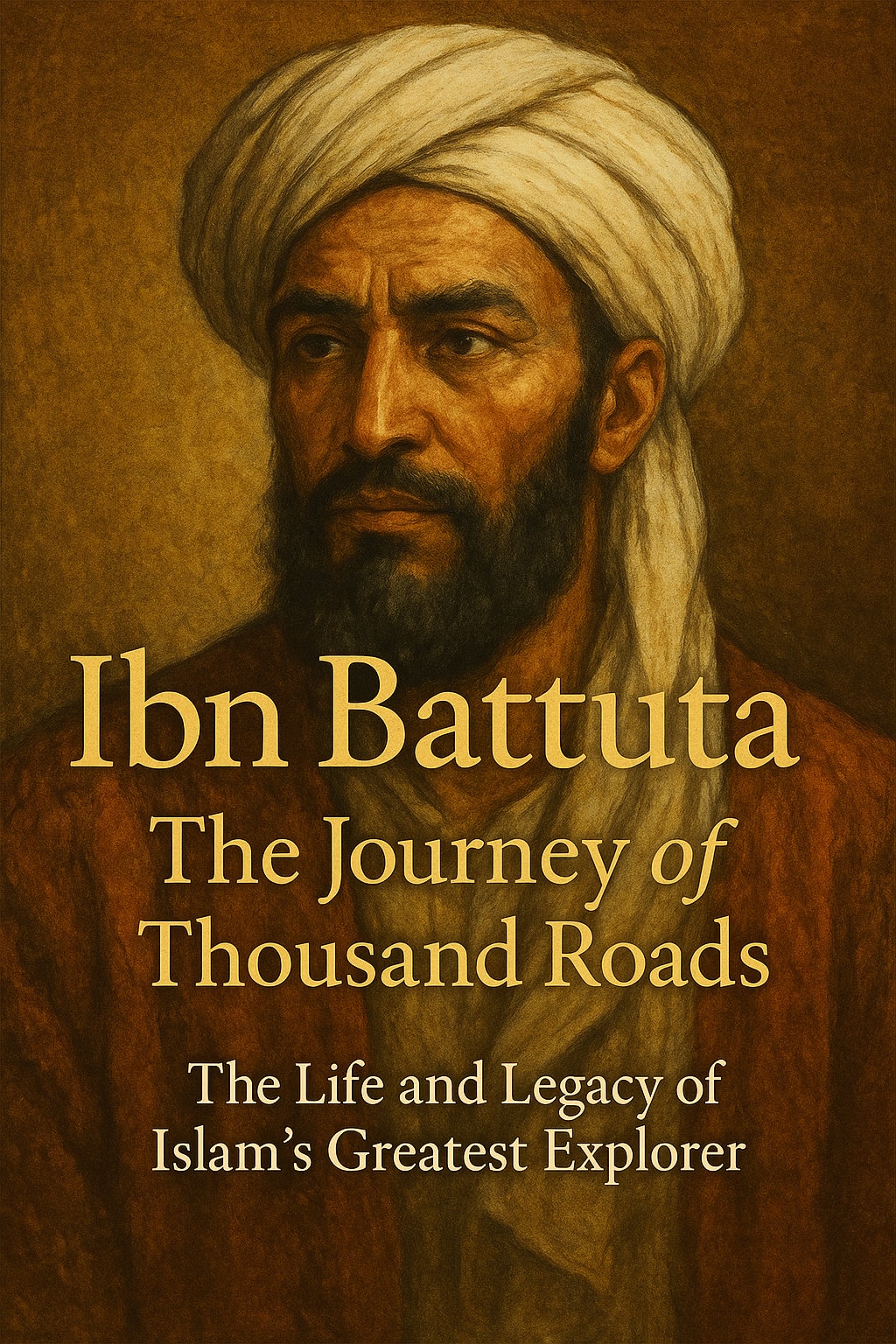

The Journey of a Thousand Roads

Tracing the Footsteps of the World’s Most Traveled Man

In an age before modern transportation, GPS, or even accurate maps, one man journeyed farther than perhaps anyone else in pre-modern history. That man was Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battuta, better known simply as Ibn Battuta. Born in 1304 in the bustling city of Tangier, in present-day Morocco, Ibn Battuta’s life would become a testament to the spirit of exploration, the thirst for knowledge, and the unshakable strength of faith.

Early Life and the Call to Travel

Ibn Battuta was born into a well-educated Berber family of Islamic legal scholars. As a young man raised in a religious household, he was expected to pursue a life in Islamic jurisprudence. But at the age of 21, his life took a radical turn when he set off on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca. What began as a religious duty soon transformed into a 30-year odyssey covering over 75,000 miles and more than 40 modern countries.

Unlike many travelers of the medieval Islamic world, Ibn Battuta did not travel as part of a royal expedition or trade caravan. Instead, he traveled largely on his own, relying on the hospitality of fellow Muslims, the protection of the faith-based legal system, and the networks of scholars and Sufi lodges that dotted the Islamic world.

The First Journey: North Africa to Mecca

His first journey took him across North Africa, through Egypt and the Levant, to Mecca. Along the way, he passed through Cairo, Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Damascus—cities teeming with cultural, religious, and intellectual life. He was struck by the grandeur of the Mamluk Empire and the vibrant Islamic institutions of learning.

When he arrived in Mecca, he performed the pilgrimage and stayed for some time, studying and deepening his knowledge of Islamic law. However, rather than returning home, Ibn Battuta chose to keep going. He once wrote, “I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveler in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose party I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries.”

Eastward Bound: Persia, India, and the Far East

Ibn Battuta journeyed through Iraq and Persia before heading to the Indian subcontinent. There, he entered the service of the Delhi Sultanate under Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, who appointed him as a qadi (Islamic judge). He stayed in India for nearly a decade, serving in the royal court. But political instability and suspicion eventually made his position untenable.

Seizing an opportunity, Ibn Battuta was sent as an envoy of the Sultan to the Yuan Dynasty court in China. His voyage took him through the Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. He marveled at the different customs, dress, and faith expressions across these regions, often comparing them to the Islamic standards of his homeland. Although his descriptions of China are relatively brief and may contain secondhand accounts, they still provide rare insight into 14th-century East Asia through a Muslim lens.

The Return Journey: Africa, Andalusia, and Mali

After traveling back west, Ibn Battuta eventually returned to Mecca and then headed home to Morocco—nearly 24 years after he had left. But his wanderlust had not yet been satisfied.

Soon, he traveled again, this time to Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), where he admired the sophistication of the Islamic cities and lamented the ongoing Christian reconquest. From there, he made one of his most remarkable journeys: to the Mali Empire in West Africa. He visited the legendary city of Timbuktu, describing it as a center of Islamic learning and commerce. His account of Mansa Musa’s empire remains one of the few firsthand sources we have of medieval West Africa.

Legacy: The Rihla

When Ibn Battuta finally returned to Morocco for good in 1354, the Sultan of Fez commissioned a scholar named Ibn Juzayy to help him compile his experiences into a travel memoir. The result was “Al-Rihla” (The Journey), a rich narrative that is equal parts autobiography, geography, anthropology, and religious commentary.

In it, Ibn Battuta chronicled not just places but people, customs, foods, dress, and spiritual practices. His observations range from deeply insightful to morally judgmental, often shaped by his background as a jurist. His writing provides an unparalleled view of the Islamic world during its Golden Age, when Muslim lands stretched from Spain to China.

A Man of His Time

Ibn Battuta was not a modern ethnographer. His observations were filtered through his religious and cultural beliefs. He was often critical of practices he viewed as un-Islamic and was sometimes dismissive of foreign customs. Yet his work offers one of the most expansive portraits of the pre-modern world.

Unlike Marco Polo, whose travels predate his, Ibn Battuta traveled not as a merchant but as a seeker of knowledge and faith. While Polo viewed the East with wonder and foreignness, Ibn Battuta often saw it as a distant part of a shared Islamic civilization, bound together by faith, law, and language.

Death and Enduring Influence

Ibn Battuta likely died around 1368 or 1369, in his hometown of Tangier. Though his fame waned after his death, his Rihla was rediscovered centuries later and is now considered a priceless source of historical and cultural information.

Today, Ibn Battuta is celebrated not only as an explorer but as a bridge between cultures. His journeys showed the vastness of the world, the diversity of its people, and the potential for knowledge to transcend borders.

Conclusion

Ibn Battuta’s life is a powerful reminder that the thirst for knowledge and adventure is universal. He saw more of the Earth than almost any of his contemporaries, documented it with sharp detail and human curiosity, and left behind a legacy that still captures the imagination of scholars and travelers alike.

In an era where much of the world was unknown and travel was perilous, Ibn Battuta walked the thousand roads—and in doing so, carved a path through history that endures to this day.

About the Creator

Irshad Abbasi

Ali ibn Abi Talib (RA) said 📚

“Knowledge is better than wealth, because knowledge protects you, while you have to protect wealth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.