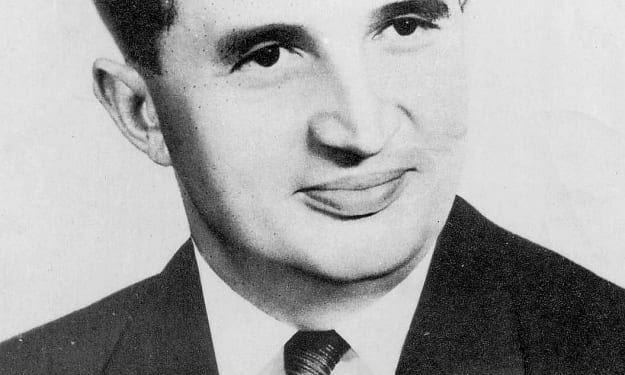

Sophie Germain

A Life of Perseverance and Devotion to Knowledge

Born in Paris in 1776, Sophie Germain grew up in an era when women were excluded from academic and scientific circles. Despite being denied a formal mathematical education in her youth and facing exclusion from the male-dominated scientific hierarchy later in life, Sophie never abandoned her passion for learning and exploration. Captivated by numbers from a young age, she found in mathematics an outlet for her creativity and boundless curiosity. Incredibly, she taught herself Latin and Greek to read mathematical texts that weren’t available in French.

The daughter of Marie-Madeleine Gruguelin and Ambroise-François Germain, she was raised in a liberal household. Though her family never fully understood her interests, this did not dampen her enthusiasm for the exact sciences. Sophie persevered in her education in secret, cultivating a profound love for number theory—marking the beginning of her extraordinary journey of discovery.

In 1794, when Germain was 18, the École Polytechnique opened. As a woman, she was barred from attending, but the new educational system made lecture notes available to anyone who requested them. It also required students to submit written observations. Germain obtained the lecture notes and began sending her work to Joseph-Louis Lagrange—under a male pseudonym, “M. Le Blanc,” to be taken seriously by the scientific community. When Lagrange recognized the brilliance of her work, he requested a meeting. Sophie was then forced to reveal her true identity. Fortunately, Lagrange was unbothered by the revelation and became her mentor.

One of the highlights of Sophie Germain’s career was her work on Fermat’s Last Theorem. A century after Fermat’s death, only the cases for n = 3 and n = 4 had been proven. Sophie tackled the problem by dividing it into two cases and proposing theorems to support each division. Collaborating with mathematicians such as Legendre and Dirichlet, she succeeded in extending the proof to additional cases.

Germain also ventured into applied physics and the study of elasticity. Her research on the deformation of solid bodies under external forces led to breakthroughs in understanding material strength and the construction of safe structures. Her participation in a Paris Academy of Sciences competition made her the first woman to win its prize—and the first to attend its sessions.

Her work was pivotal to the eventual construction of the Eiffel Tower, yet her name is absent from the list of scientists credited with making the project possible.

In 1829, Germain was diagnosed with breast cancer. Despite the pain, she continued her research. In 1831, Crelle's Journal published her paper on the curvature of elastic surfaces. That same year, she also published in Annales de Chimie et de Physique, presenting principles that led to the discovery of the laws governing equilibrium and motion in elastic solids. Finally, on 27 June 1831, she died at her home on 13 rue de Savoie.

Sophie Germain remains an enduring example of how passion and perseverance can lead to groundbreaking achievements in any field. Her story testifies to the power of the human mind and the determination to transcend limitations—leaving a lasting mark on the world.

"The pleasure for abstract sciences and for the mystery of numbers is strange, since the wonder of this science only manifests itself to those who have the courage to delve into it. But a woman, because of her sex and our customs and prejudices, encounters infinitely more obstacles and difficulties than a man in becoming familiar with the problems of mathematics. Her research indicates that she possesses remarkable courage, extraordinary talent, and a superior genius. I admire the ease with which she delves into all branches of arithmetic and the sagacity with which she has been able to generalize and go deeper."

— From a letter Carl F. Gauss sent to Germain after discovering her identity

.

Comments (1)

Sophie Germain's story is inspiring. Despite obstacles, she taught herself and made huge contributions to math, like with Fermat's Last Theorem. She overcame gender barriers to pursue her passion. Her determination to learn and prove herself is truly remarkable.