Operation Vegetarian: The Secret Plan That Was Supposed to Starve Germany and Destroyed Gruinard Island

On the northwest coast of Scotland lies the small island of Gruinard. It is approximately 2 kilometers long, uninhabited, and at first glance unremarkable. For much of the 20th century, however, it ranked among the most dangerous places in the United Kingdom.

The reason was its role during the Second World War, when its isolated location made Gruinard the ideal site for Britain's first open-air tests of biological weapons.

Bacillus anthracis

As the Second World War escalated, fears grew in Britain that Nazi Germany might resort to chemical or biological weapons. The Germans already had experience with chemical attacks from the First World War, and their chemical industry had since become the largest in the world.

The British government therefore tasked scientists from the strictly secret military research facility at Porton Down with investigating the effects of potential chemical and biological weapons that could be used both defensively and in direct attacks on the enemy.

One substance that attracted particular attention was anthrax, or splenic fever — an infectious disease caused by the highly resistant bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It was a disease commonly found in livestock and wild animals, but under certain circumstances it could also infect humans. Anthrax was notorious for its high mortality rate and, above all, for the fact that the spores of this bacterium could survive for a very long time even under adverse conditions. This made it a weapon with long-term and difficult-to-control consequences.

The Course of the Experiments

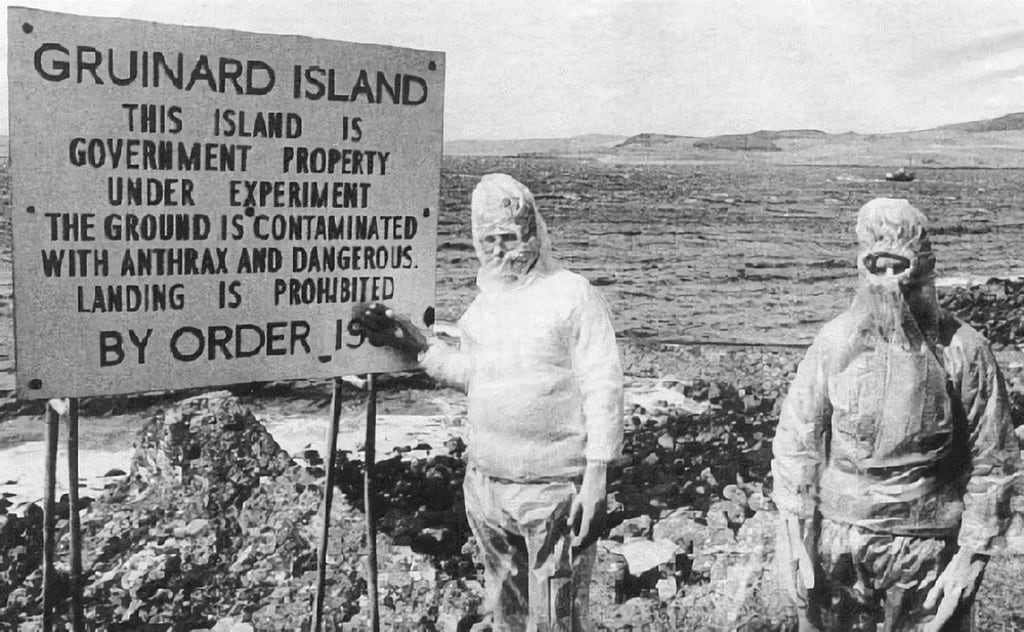

In early 1942, the first tests began on Gruinard. In one experiment, about 60 sheep were tethered on the island at various distances from containers holding anthrax spores, which were then detonated using explosives. The result was more than promising — all the test animals died. Dozens of similar tests followed. After the explosions, scientists returned to the island in protective suits to analyze the animal carcasses and study the effects of the infection. The test results clearly confirmed that anthrax was extremely effective. Only many months later, however, did they also reveal a fundamental problem: life in the affected area had become practically impossible.

Operation Vegetarian

The official position of the British government emphasized that the tests on Gruinard were purely defensive in nature and were intended to prepare the country for a possible biological attack on British territory.

In reality, however, the United Kingdom also developed theoretical plans for using these weapons against the enemy. The best-known of these became infamous under the grim name Operation Vegetarian. This plan involved dropping linen feed pellets containing anthrax spores over pastures in Germany. Cattle would eat them and die within a few hours. The infection would spread rapidly, and within days the German meat industry and army supply lines would collapse. It would all appear to be a strange coincidence. Germany would become a “land of vegetarians.”

Preparation was straightforward. Workers at the cosmetics company J&E Atkinson cut open feed pellets, filled them with a soap insert along with anthrax, and produced up to 200,000 pieces per week. The entire “secret weapon” weighed just ten grams, and a thousand pellets cost only about 15 shillings. War had never been so cheap.

Production of the deadly feed ran at full capacity. Assembly lines were modernized, pace increased, and soon the threshold of forty thousand pieces per day was surpassed. By May 1942, more than 5 million pellets were already stored in warehouses. Meanwhile, engineers were figuring out how to deliver the deadly “cakes” to the target. They designed simple transport boxes and modified several Lancaster bombers to carry death.

The plan was diabolical and terrifyingly simple. Cities and factories were accustomed to air raids, but pastures were undefended. In twenty minutes of low-level flight, it was possible to cover about eighty square kilometers. The only condition: spring — the time when meadows are teeming with livestock.

Resistance fighters across Europe received instructions to send unusual reports. They were to inform not only about troop movements but also about herds of cattle, unaware of how deadly serious this information was. New symbols appeared on the planners’ maps of Operation Vegetarian: Hannover, Oldenburg… Perhaps the Netherlands. Perhaps Austria. Perhaps occupied Czechoslovakia. The plan was ready to launch within a few months. All that remained was to fine-tune it to perfection.

Playing with Death

Fortunately, events intervened that changed the course of the war. The Germans were halted by winter at Stalingrad, and the situation slowly began to turn in favor of the Allies. Churchill hesitated over the mad operation. And this very hesitation proved crucial. It gave time for further tests. And those tests revealed a terrifying truth.

Anthrax would not kill only cattle. Soon pigs, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats would also fall. And humans too. Thousands of soldiers might die — the command might accept that. But civilians? After eating meat from infected animals, 60 to 95 percent of people would die. Without medicine, they stood no chance. Disrupting supplies is one thing. Poisoning ordinary people is another. And that could no longer be excused even by war.

Moreover, the tests on Gruinard showed that while the pellets broke down quickly in the soil, the anthrax spores remained. They clung to the ground like a curse and could survive for decades. Widespread bombing would turn continental Europe into a dead continent — not for months, but for entire generations.

After the war ended, Gruinard Island was therefore strictly closed off. Only scientists had access, regularly testing the level of soil contamination. The millions of produced pellets were quietly incinerated in furnaces at Porton Down, and the files containing plans for biological attack were archived in military storage.

The British began referring to the island as a “contaminated monster.”

Return to Safety

It was not until the 1980s that the British government decided on large-scale decontamination. Vaccinated workers in protective suits sprayed the upper soil layer with a mixture of formaldehyde and seawater. Approximately 50 liters of solution were applied per square meter.

In the summer of 1987, a flock of sheep was placed on the island, and fortunately no signs of illness appeared. Based on these results, the British Ministry of Defence officially declared Gruinard safe the following year. The island was then sold to the heirs of the original owner for a symbolic sum of 500 pounds. Nevertheless, it remains uninhabited to this day.

Today, Gruinard Island serves as a concrete reminder of how long-lasting — and often irreversible — the consequences of using biological weapons can be, even when they are never actually deployed in combat.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.