In the heart of the Swat Valley, nestled between mountains and rivers, lay a quiet village named Derai. Known for its beautiful orchards and strong community spirit, Derai was also known for something else: its old rules.

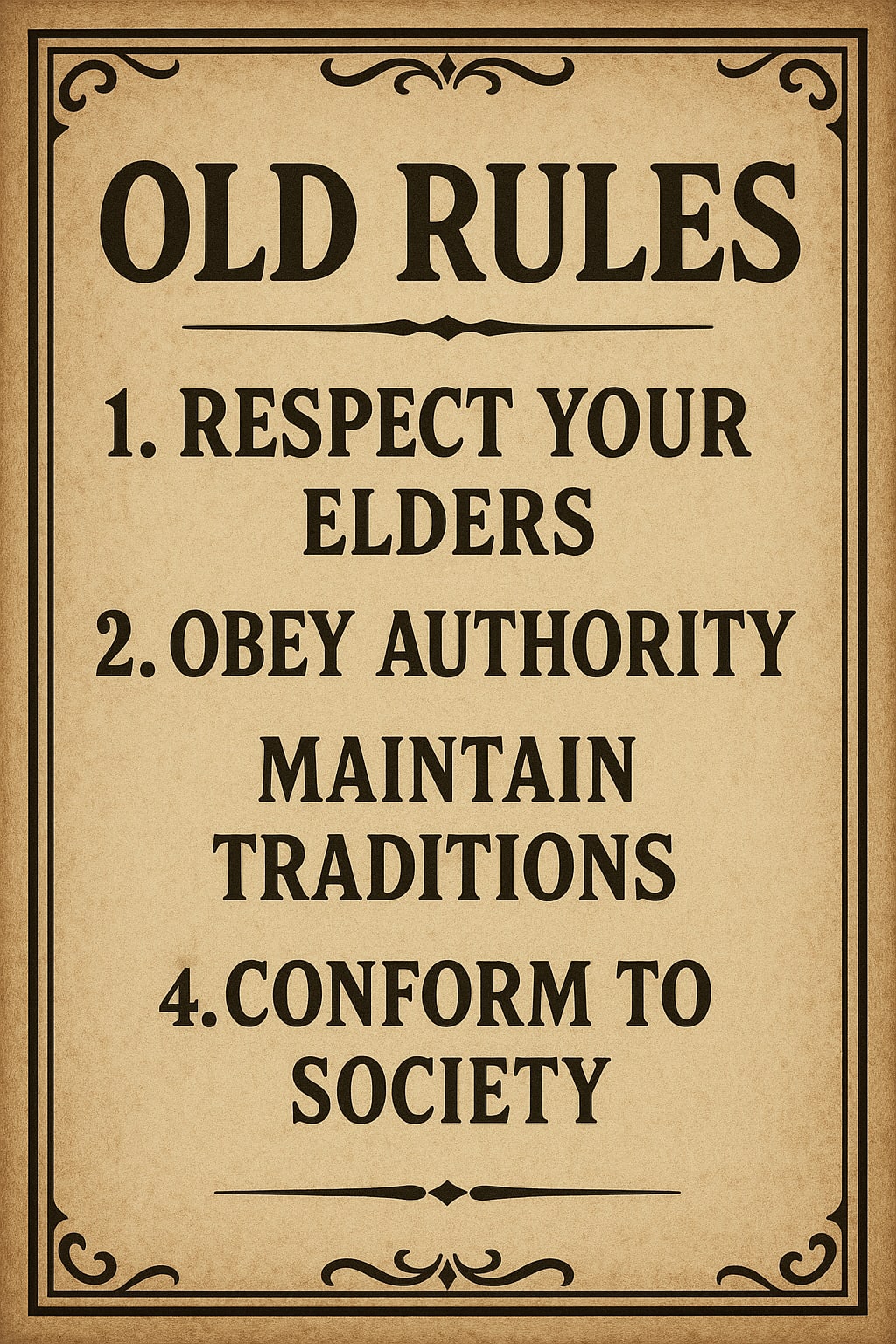

These rules were written down over a hundred years ago by the village elders, etched into stone and memorized by every household. They governed everything—from how land was divided to how disputes were settled. The rules forbade things like girls going to school, the use of mobile phones, or any change in farming methods. The villagers called it Riwaj, the sacred tradition.

For years, the old rules served the village well. But as the world outside began to change, the youth of Derai began to question them.

Among them was a boy named Ayan. At seventeen, Ayan was curious, bold, and smart. He loved reading, especially books about science and technology. His father, Gul Rahman, was a farmer and a firm believer in the old rules. He often warned Ayan, “The old ways are the best ways. Don’t bring trouble by challenging them.”

But Ayan couldn’t help himself.

One day, Ayan brought home a solar-powered water pump he had built using old parts and some help from YouTube videos. The pump could help the farmers irrigate their land more efficiently, especially during power outages. Excited, he demonstrated it to his father.

Gul Rahman was stunned. It worked. The water flowed steadily from the pump, and the fields drank it eagerly. But instead of joy, fear settled on his face.

“If the elders see this, they’ll say it’s against the Riwaj,” he warned. “They’ll accuse you of bringing outside influence.”

“But Baba,” Ayan replied, “isn’t it better than letting crops die? Isn’t helping the village more important than following old rules blindly?”

Gul Rahman had no answer.

News of the pump spread quickly, and within days, the village jirga (council) summoned Ayan. The jirga consisted of white-bearded men who sat on carved wooden chairs, with the Riwaj stones laid out before them.

The head of the jirga, Haji Meeran, spoke first.

“Young man, we heard you have brought something new into our village. A machine that defies tradition. Is this true?”

“Yes, Haji Sahib,” Ayan replied respectfully. “But it is not to defy. It is to improve.”

Another elder scoffed. “Improvement? Our ancestors survived without machines. So can we.”

“But our ancestors also walked for miles to fetch water. Do we still do that?” Ayan asked. “They lit lamps with oil. Should we break our bulbs and go back to darkness?”

A silence fell.

Ayan continued, “Respecting our traditions doesn’t mean we stop thinking. We can honor the past and still move forward. My invention doesn’t break Riwaj—it saves our land.”

Some elders looked at each other. Others frowned.

Then Haji Meeran stood up. “The boy speaks with wisdom. Maybe it is time we review the old rules. The world is changing. Perhaps we too must adapt, not abandon our ways, but evolve them.”

It was a turning point.

For the first time in decades, the jirga agreed to form a small committee of young and old members to review the Riwaj. They decided that rules harming progress or education would be discussed and possibly revised.

Girls were slowly allowed to attend the village school. Farmers started adopting modern techniques. Mobile phones were still restricted in some areas, but the wall was cracking. The village began to breathe.

Gul Rahman watched his son with pride. “You did what I was afraid to even imagine,” he said one evening.

“I only asked questions,” Ayan replied, smiling. “Sometimes, that’s all it takes to start change.”

Years later, Derai became known not just for its orchards, but also as a model village in the Swat Valley—where old rules were honored, but not worshipped, and where new ideas were welcomed, not feared.

And on one of the original Riwaj stones, a new line was carved:

There were rules for everything: how to dress, how to speak, how to farm, how to resolve disputes, and most importantly, how to behave. These rules were enforced by the village elders, known as the Masharan, who sat in the hujra every evening, discussing matters and passing judgments.

The most feared of all the rules was this: “No one shall question the way things have always been.”

But in every generation, there comes someone who dares to ask “why.”

This time, it was a 16-year-old boy named Saifullah. Curious by nature and always dreaming beyond the mountains, Saifullah had grown up watching the elders hold tight to traditions—even when they caused harm. He had seen his cousin denied the chance to study beyond primary school because “girls don’t need education.” He had watched his neighbor lose land in a dispute simply because he was younger and the elder opponent had a louder voice. He had seen farming methods fail year after year due to outdated practices, while nearby towns used modern irrigation.

Saifullah’s heart ached, but he remained silent—until the day his younger sister, Zarmeena, cried herself to sleep.

She had passed her 8th-grade exams with the highest marks in the school. She dreamed of becoming a doctor. But their father, pressured by the village elders, told her she would no longer be allowed to attend school.

“When old rules serve the people, keep them. When they hurt the people, change them.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.