Jinnah" redirects here

For other uses, see Jinnah (Part two)

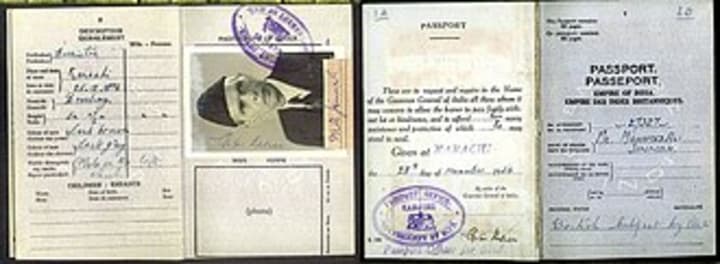

Wilderness years; interlude in England

Jinnah's passport

The alliance between Gandhi and the Khilafat faction did not last long, and the campaign of resistance proved less effective than hoped, as India's institutions continued to function. Jinnah sought alternative political ideas, and contemplated organising a new political party as a rival to the Congress. In September 1923, Jinnah was elected as Muslim member for Bombay in the new Central Legislative Assembly. He showed much skill as a parliamentarian, organising many Indian members to work with the Swaraj Party, and continued to press demands for full responsible government. In 1925, as recognition for his legislative activities, he was offered a knighthood by Lord Reading, who was retiring from the Viceroyalty. He replied: "I prefer to be plain Mr Jinnah."[66]

In 1927, the British Government, under Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, undertook a decennial review of Indian policy mandated by the Government of India Act 1919. The review began two years early as Baldwin feared he would lose the next election (which he did, in 1929). The Cabinet was influenced by minister Winston Churchill, who strongly opposed self-government for India, and members hoped that by having the commission appointed early, the policies for India which they favoured would survive their government. The resulting commission, led by Liberal MP John Simon, though with a majority of Conservatives, arrived in India in March 1928.[67] They were met with a boycott by India's leaders, Muslim and Hindu alike, angered at the British refusal to include their representatives on the commission. A minority of Muslims, though, withdrew from the League, choosing to welcome the Simon Commission and repudiating Jinnah. Most members of the League's executive council remained loyal to Jinnah, attending the League meeting in December 1927 and January 1928 which confirmed him as the League's permanent president. At that session, Jinnah told the delegates that "A constitutional war has been declared on Great Britain. Negotiations for a settlement are not to come from our side ... By appointing an exclusively white Commission, [Secretary of State for India] Lord Birkenhead has declared our unfitness for self-government."[68]

Birkenhead in 1928 challenged Indians to come up with their own proposal for constitutional change for India; in response, the Congress convened a committee under the leadership of Motilal Nehru.[1] The Nehru Report favoured constituencies based on geography on the ground that being dependent on each other for election would bind the communities closer together. Jinnah, though he believed separate electorates, based on religion, necessary to ensure Muslims had a voice in the government, was willing to compromise on this point, but talks between the two parties failed. He put forth proposals that he hoped might satisfy a broad range of Muslims and reunite the League, calling for mandatory representation for Muslims in legislatures and cabinets. These became known as his Fourteen Points. He could not secure adoption of the Fourteen Points, as the League meeting in Delhi at which he hoped to gain a vote instead dissolved into chaotic argument.[69]

After Baldwin was defeated at the 1929 British parliamentary election, Ramsay MacDonald of the Labour Party became prime minister. MacDonald desired a conference of Indian and British leaders in London to discuss India's future, a course of action supported by Jinnah. Three Round Table Conferences followed over as many years, none of which resulted in a settlement. Jinnah was a delegate to the first two conferences, but was not invited to the last.[70] He remained in Britain for most of the period 1930 through 1934, practising as a barrister before the Privy Council, where he dealt with a number of India-related cases. His biographers disagree over why he remained so long in Britain—Wolpert asserts that had Jinnah been made a Law Lord, he would have stayed for life, and that Jinnah alternatively sought a parliamentary seat.[71][72] Early biographer Hector Bolitho denied that Jinnah sought to enter the British Parliament,[71] while Jaswant Singh deems Jinnah's time in Britain as a break or sabbatical from the Indian struggle.[73] Bolitho called this period "Jinnah's years of order and contemplation, wedged in between the time of early struggle, and the final storm of conquest".[74]

In 1931, Fatima Jinnah joined her brother in England. From then on, Muhammad Ali Jinnah would receive personal care and support from her as he aged and began to suffer from the lung ailments which would eventually kill him. She lived and travelled with him, and became a close advisor. Muhammad Jinnah's daughter, Dina, was educated in England and India. Jinnah later became estranged from Dina after she decided to marry a Parsi, Neville Wadia from a prominent business family. When Jinnah urged Dina to marry a Muslim, she reminded him that he had married a woman not raised in his faith. Jinnah continued to correspond cordially with his daughter, but their personal relationship was strained, and she did not come to Pakistan in his lifetime, but only for his funeral.

Return to politics

The early 1930s saw a resurgence in Indian Muslim nationalism, which came to a head with the Pakistan Declaration. In 1933, Indian Muslims, especially from the United Provinces, began to urge Jinnah to return and take up again his leadership of the Muslim League, an organisation which had fallen into inactivity.[77] He remained titular president of the League,[d] but declined to travel to India to preside over its 1933 session in April, writing that he could not possibly return there until the end of the year.[78]

Among those who met with Jinnah to seek his return was Liaquat Ali Khan, who would be a major political associate of Jinnah in the years to come and the first prime minister of Pakistan. At Jinnah's request, Liaquat discussed the return with a large number of Muslim politicians and confirmed his recommendation to Jinnah.[79][80] In early 1934, Jinnah relocated to the subcontinent, though he shuttled between London and India on business for the next few years, selling his house in Hampstead and closing his legal practice in Britain.[81][82]

Muslims of Bombay elected Jinnah, though then absent in London, as their representative to the Central Legislative Assembly in October 1934.[83][84] The British Parliament's Government of India Act 1935 gave considerable power to India's provinces, with a weak central parliament in New Delhi, which had no authority over such matters as foreign policy, defence, and much of the budget. Full power remained in the hands of the Viceroy, however, who could dissolve legislatures and rule by decree. The League reluctantly accepted the scheme, though expressing reservations about the weak parliament. The Congress was much better prepared for the provincial elections in 1937, and the League failed to win a majority even of the Muslim seats in any of the provinces where members of that faith held a majority. It did win a majority of the Muslim seats in Delhi, but could not form a government anywhere, though it was part of the ruling coalition in Bengal. The Congress and its allies formed the government even in the North-West Frontier Province (N.W.F.P.), where the League won no seats despite the fact that almost all residents were Muslim.[85]

Jinnah (front, left) with the Working Committee of the Muslim League after a meeting in Lucknow, October 1937

According to Jaswant Singh, "the events of 1937 had a tremendous, almost a traumatic effect upon Jinnah".[86] Despite his beliefs of twenty years that Muslims could protect their rights in a united India through separate electorates, provincial boundaries drawn to preserve Muslim majorities, and by other protections of minority rights, Muslim voters had failed to unite, with the issues Jinnah hoped to bring forward lost amid factional fighting.[86][87] Singh notes the effect of the 1937 elections on Muslim political opinion, "when the Congress formed a government with almost all of the Muslim MLAs sitting on the Opposition benches, non-Congress Muslims were suddenly faced with this stark reality of near-total political powerlessness. It was brought home to them, like a bolt of lightning, that even if the Congress did not win a single Muslim seat ... as long as it won an absolute majority in the House, on the strength of the general seats, it could and would form a government entirely on its own ..."[88]

In the next two years, Jinnah worked to build support among Muslims for the League. He secured the right to speak for the Muslim-led Bengali and Punjabi provincial governments in the central government in New Delhi ("the centre"). He worked to expand the League, reducing the cost of membership to two annas (1⁄8 of a rupee), half of what it cost to join the Congress. He restructured the League along the lines of the Congress, putting most power in a Working Committee, which he appointed.[89] By December 1939, Liaquat estimated that the League had three million two-anna members.

Struggle for Pakistan

Main article: Pakistan Movement

Background to independence

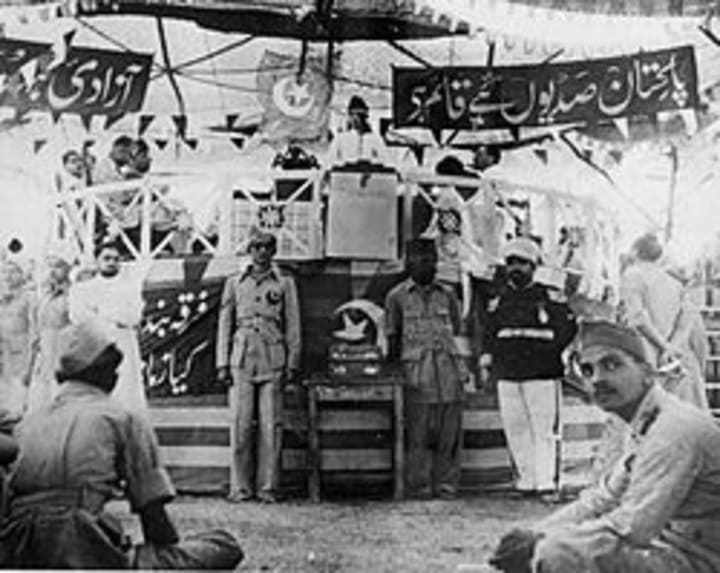

Jinnah addresses the Muslim League session at Patna, 1938

Until the late 1930s, most Muslims of the British Raj expected, upon independence, to be part of a unitary state encompassing all of British India, as did the Hindus and others who advocated self-government.[91] Despite this, other nationalist proposals were being made. In a speech given at Allahabad to a League session in 1930, Sir Muhammad Iqbal called for a state for Muslims in British India. Choudhary Rahmat Ali published a pamphlet in 1933 advocating a state "Pakistan" in the Indus Valley, with other names given to Muslim-majority areas elsewhere in India.[92] Jinnah and Iqbal corresponded in 1936 and 1937; in subsequent years, Jinnah credited Iqbal as his mentor and used Iqbal's imagery and rhetoric in his speeches.[93]

Although many leaders of the Congress sought a strong central government for an Indian state, some Muslim politicians, including Jinnah, were unwilling to accept this without powerful protections for their community.[91] Other Muslims supported the Congress, which officially advocated a secular state upon independence, though the traditionalist wing (including politicians such as Madan Mohan Malaviya and Vallabhbhai Patel) believed that an independent India should enact laws such as banning the slaughter of cows and making Hindi a national language. The failure of the Congress leadership to disavow Hindu communalists worried Congress-supporting Muslims. Nevertheless, the Congress enjoyed considerable Muslim support up to about 1937.[94]

Events which separated the communities included the failed attempt to form a coalition government including the Congress and the League in the United Provinces following the 1937 election.[95] According to historian Ian Talbot, "The provincial Congress governments made no effort to understand and respect their Muslim populations' cultural and religious sensibilities. The Muslim League's claims that it alone could safeguard Muslim interests thus received a major boost. Significantly it was only after this period of Congress rule that it [the League] took up the demand for a Pakistan state ..."[84]

Balraj Puri in his journal article about Jinnah suggests that the Muslim League president, after the 1937 vote, turned to the idea of partition in "sheer desperation".[96] Historian Akbar S. Ahmed suggests that Jinnah abandoned hope of reconciliation with the Congress as he "rediscover[ed] his own Islamic roots, his own sense of identity, of culture and history, which would come increasingly to the fore in the final years of his life".[16] Jinnah also increasingly adopted Muslim dress in the late 1930s.[97] In the wake of the 1937 balloting, Jinnah demanded that the question of power sharing be settled on an all-India basis, and that he, as president of the League, be accepted as the sole spokesman for the Muslim community.

Iqbal's influence on Jinnah

Jinnah seated with Iqbal at the round table conference

The well documented influence of Iqbal on Jinnah, with regard to taking the lead in creating Pakistan, has been described as "significant", "powerful" and even "unquestionable" by scholars.[100][101][102] Iqbal has also been cited as an influential force in convincing Jinnah to end his self-imposed exile in London and re-enter the politics of India.[103][104][105][106] Initially, however, Iqbal and Jinnah were opponents, as Iqbal believed Jinnah did not care about the crises confronting the Muslim community during the British Raj. According to Akbar S. Ahmed, this began to change during Iqbal's final years prior to his death in 1938. Iqbal gradually succeeded in converting Jinnah over to his view, who eventually accepted Iqbal as his mentor. Ahmed comments that in his annotations to Iqbal's letters, Jinnah expressed solidarity with Iqbal's view: that Indian Muslims required a separate homeland.[107]

Iqbal's influence also gave Jinnah a deeper appreciation for Muslim identity.[108] The evidence of this influence began to be revealed from 1937 onwards. Jinnah not only began to echo Iqbal in his speeches, he started using Islamic symbolism and began directing his addresses to the underprivileged. Ahmed noted a change in Jinnah's words: while he still advocated freedom of religion and protection of the minorities, the model he was now aspiring to was that of the Prophet Muhammad, rather than that of a secular politician. Ahmed further avers that those scholars who have painted the later Jinnah as secular have misread his speeches which, he argues, must be read in the context of Islamic history and culture. Accordingly, Jinnah's imagery of the Pakistan began to become clear that it was to have an Islamic nature. This change has been seen to last for the rest of Jinnah's life. He continued to borrow ideas "directly from Iqbal—including his thoughts on Muslim unity, on Islamic ideals of liberty, justice and equality, on economics, and even on practices such as prayers".[109][100]

In a speech in 1940, two years after the death of Iqbal, Jinnah expressed his preference for implementing Iqbal's vision for an Islamic Pakistan even if it meant he himself would never lead a nation. Jinnah stated, "If I live to see the ideal of a Muslim state being achieved in India, and I was then offered to make a choice between the works of Iqbal and the rulership of the Muslim state, I would prefer the former.

Second World War and Lahore Resolution

Main article: Lahore Resolution

The leaders of the Muslim League, 1940. Jinnah is seated at centre.

On 3 September 1939, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced the commencement of war with Nazi Germany.[111] The following day, the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, without consulting Indian political leaders, announced that India had entered the war along with Britain. There were widespread protests in India. After meeting with Jinnah and with Gandhi, Linlithgow announced that negotiations on self-government were suspended for the duration of the war.[112] The Congress on 14 September demanded immediate independence with a constituent assembly to decide a constitution; when this was refused, its eight provincial governments resigned on 10 November and governors in those provinces thereafter ruled by decree for the remainder of the war. Jinnah, on the other hand, was more willing to accommodate the British, and they in turn increasingly recognised him and the League as the representatives of India's Muslims.[113] Jinnah later stated, "after the war began, ... I was treated on the same basis as Mr Gandhi. I was wonderstruck why I was promoted and given a place side by side with Mr Gandhi."[114] Although the League did not actively support the British war effort, neither did they try to obstruct it.

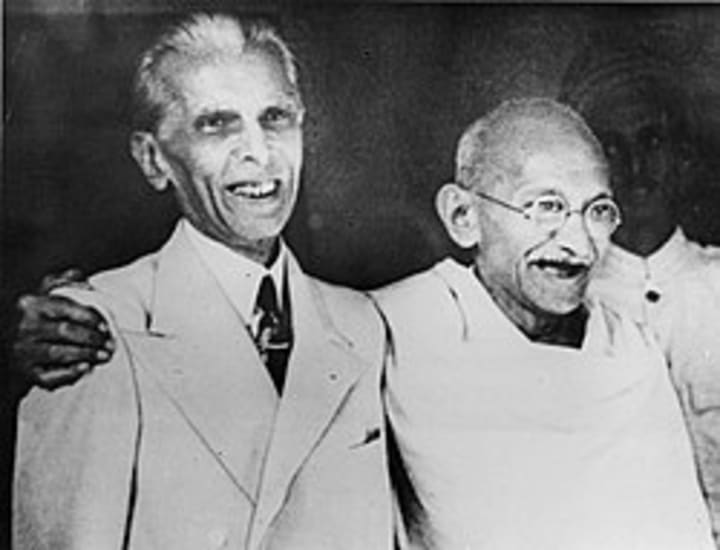

Jinnah and Gandhi arguing after a meeting between them in Delhi, November 1939

With the British and Muslims to some extent co-operating, the Viceroy asked Jinnah for an expression of the Muslim League's position on self-government, confident that it would differ greatly from that of the Congress. To come up with such a position, the League's Working Committee met for four days in February 1940 to set out terms of reference to a constitutional sub-committee. The Working Committee asked that the sub-committee return with a proposal that would result in "independent dominions in direct relationship with Great Britain" where Muslims were dominant.[116] On 6 February, Jinnah informed the Viceroy that the Muslim League would be demanding partition instead of the federation contemplated in the 1935 Act. The Lahore Resolution (sometimes called the "Pakistan Resolution", although it does not contain that name), based on the sub-committee's work, embraced the two-nation theory and called for a union of the Muslim-majority provinces in the northwest of British India, with complete autonomy. Similar rights were to be granted to the Muslim-majority areas in the east, and unspecified protections given to Muslim minorities in other provinces. The resolution was passed by the League session in Lahore on 23 March 1940

Jinnah makes a speech in New Delhi, 1943

Gandhi's reaction to the Lahore Resolution was muted; he called it "baffling", but told his disciples that Muslims, in common with other people of India, had the right to self-determination. Leaders of the Congress were more vocal; Jawaharlal Nehru referred to Lahore as "Jinnah's fantastic proposals" while Chakravarti Rajagopalachari deemed Jinnah's views on partition "a sign of a diseased mentality".[119] Linlithgow met with Jinnah in June 1940,[120] soon after Winston Churchill became the British prime minister, and in August offered both the Congress and the League a deal whereby in exchange for full support for the war, Linlithgow would allow Indian representation on his major war councils. The Viceroy promised a representative body after the war to determine India's future, and that no future settlement would be imposed over the objections of a large part of the population. This was satisfactory to neither the Congress nor the League, though Jinnah was pleased that the British had moved towards recognising Jinnah as the representative of the Muslim community's interests.[121] Jinnah was reluctant to make specific proposals as to the boundaries of Pakistan, or its relationships with Britain and with the rest of the subcontinent, fearing that any precise plan would divide the League

Jinnah with Mahatma Gandhi in Bombay, September 1944

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the United States into the war. In the following months, the Japanese advanced in Southeast Asia, and the British Cabinet sent a mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps to try to conciliate the Indians and cause them to fully back the war. Cripps proposed giving some provinces what was dubbed the "local option" to remain outside of an Indian central government either for a period of time or permanently, to become dominions on their own or be part of another confederation. The Muslim League was far from certain of winning the legislative votes that would be required for mixed provinces such as Bengal and Punjab to secede, and Jinnah rejected the proposals as not sufficiently recognising Pakistan's right to exist. The Congress also rejected the Cripps plan, demanding immediate concessions which Cripps was not prepared to give.[123][124] Despite the rejection, Jinnah and the League saw the Cripps proposal as recognising Pakistan in principle.[125]

The Congress followed the failed Cripps mission by demanding, in August 1942, that the British immediately "Quit India", proclaiming a mass campaign of satyagraha until they did. The British promptly arrested most major leaders of the Congress and imprisoned them for the remainder of the war. Gandhi, however, was placed on house arrest in one of the Aga Khan's palaces prior to his release for health reasons in 1944. With the Congress leaders absent from the political scene, Jinnah warned against the threat of Hindu domination and maintained his Pakistan demand without going into great detail about what that would entail. Jinnah also worked to increase the League's political control at the provincial level.[126][127] He helped to found the newspaper Dawn in the early 1940s in Delhi; it helped to spread the League's message and eventually became the major English-language newspaper of Pakistan.[128] He also started living in Delhi on Aurangzeb Road (now Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Road), near Birla House where Mahatma Gandhi stayed and Jinnah was neighbours with the wealthiest man in Delhi at the time, Sir Sobha Singh.[129] His house is now the Embassy of Netherlands in India and is known as Jinnah House by most.[130]

In September 1944, Jinnah hosted Gandhi, recently released from confinement, at his home on Malabar Hill in Bombay. Two weeks of talks between them followed, which resulted in no agreement. Jinnah insisted on Pakistan being conceded prior to the British departure and to come into being immediately, while Gandhi proposed that plebiscites on partition occur sometime after a united India gained its independence.[131] In early 1945, Liaquat and the Congress leader Bhulabhai Desai met, with Jinnah's approval, and agreed that after the war, the Congress and the League should form an interim government with the members of the Executive Council of the Viceroy to be nominated by the Congress and the League in equal numbers. When the Congress leadership were released from prison in June 1945, they repudiated the agreement and censured Desai for acting without proper authority

Postwar

Nehru (left) and Jinnah walk together at Simla, 1946

Field Marshal Viscount Wavell succeeded Linlithgow as Viceroy in 1943. In June 1945, following the release of the Congress leaders, Wavell called for a conference, and invited the leading figures from the various communities to meet with him at Simla. He proposed a temporary government along the lines which Liaquat and Desai had agreed. However, Wavell was unwilling to guarantee that only the League's candidates would be placed in the seats reserved for Muslims. All other invited groups submitted lists of candidates to the Viceroy. Wavell cut the conference short in mid-July without further seeking an agreement; with a British general election imminent, Churchill's government did not feel it could proceed.[133]

British voters returned Clement Attlee and his Labour Party to government later in July. Attlee and his Secretary of State for India, Lord Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, immediately ordered a review of the Indian situation.[134] Jinnah had no comment on the change of government, but called a meeting of his Working Committee and issued a statement calling for new elections in India. The League held influence at the provincial level in the Muslim-majority states mostly by alliance, and Jinnah believed that, given the opportunity, the League would improve its electoral standing and lend added support to his claim to be the sole spokesman for the Muslims. Wavell returned to India in September after consultation with his new masters in London; elections, both for the centre and for the provinces, were announced soon after. The British indicated that formation of a constitution-making body would follow the votes

Jinnah with Muslim League leaders in the corridor of the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi in 1946

The Muslim League declared that they would campaign on a single issue: Pakistan.[136] Speaking in Ahmedabad, Jinnah echoed this, "Pakistan is a matter of life or death for us."[137] In the December 1945 elections for the Constituent Assembly of India, the League won every seat reserved for Muslims. In the provincial elections in January 1946, the League took 75% of the Muslim vote, an increase from 4.4% in 1937.[138] According to his biographer Bolitho, "This was Jinnah's glorious hour: his arduous political campaigns, his robust beliefs and claims, were at last justified."[139] Wolpert wrote that the League election showing "appeared to prove the universal appeal of Pakistan among Muslims of the subcontinent".[140] The Congress dominated the central assembly nevertheless, though it lost four seats from its previous strength

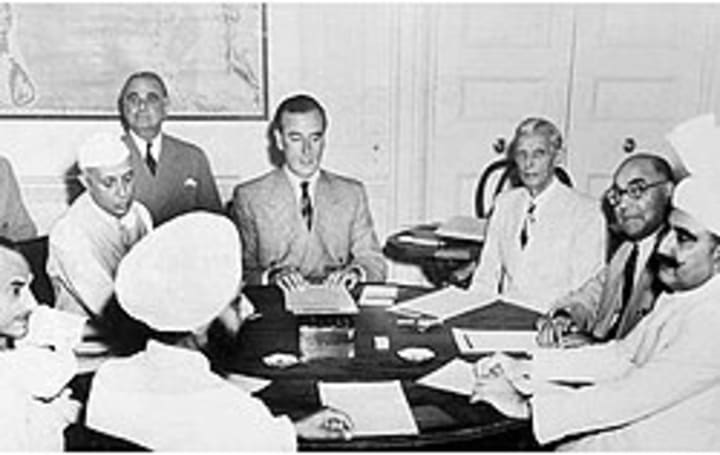

Jinnah with Stafford Cripps (right) and Pethick-Lawrence (left)

In February 1946, the British Cabinet resolved to send a delegation to India to negotiate with leaders there. This Cabinet Mission included Cripps and Pethick-Lawrence. The highest-level delegation to try to break the deadlock, it arrived in New Delhi in late March. Little negotiation had been done since the previous October because of the elections in India.[141] The British in May released a plan for a united Indian state comprising substantially autonomous provinces, and called for "groups" of provinces formed on the basis of religion. Matters such as defence, external relations and communications would be handled by a central authority. Provinces would have the option of leaving the union entirely, and there would be an interim government with representation from the Congress and the League. Jinnah and his Working Committee accepted this plan in June, but it fell apart over the question of how many members of the interim government the Congress and the League would have, and over the Congress's desire to include a Muslim member in its representation. Before leaving India, the British ministers stated that they intended to inaugurate an interim government even if one of the major groups was unwilling to participate.[142]

The Congress soon joined the new Indian ministry. The League was slower to do so, not entering until October 1946. In agreeing to have the League join the government, Jinnah abandoned his demands for parity with the Congress and a veto on matters concerning Muslims. The new ministry met amid a backdrop of rioting, especially in Calcutta.[143] The Congress wanted the Viceroy to immediately summon the constituent assembly and begin the work of writing a constitution and felt that the League ministers should either join in the request or resign from the government. Wavell attempted to save the situation by flying leaders such as Jinnah, Liaquat, and Jawaharlal Nehru to London in December 1946. At the end of the talks, participants issued a statement that the constitution would not be forced on any unwilling parts of India.[144] On the way back from London, Jinnah and Liaquat stopped in Cairo for several days of pan-Islamic meetings.[145]

The Congress endorsed the joint statement from the London conference over the angry dissent from some elements. The League refused to do so, and took no part in the constitutional discussions.[144] Jinnah had been willing to consider some continued links to Hindustan (as the Hindu-majority state which would be formed on partition was sometimes referred to), such as a joint military or communications. However, by December 1946, he insisted on a fully sovereign Pakistan with dominion status.[146]

Following the failure of the London trip, Jinnah was in no hurry to reach an agreement, considering that time would allow him to gain the undivided provinces of Bengal and Punjab for Pakistan, but these wealthy, populous provinces had sizeable non-Muslim minorities, complicating a settlement.[147] The Attlee ministry desired a rapid British departure from the subcontinent, but had little confidence in Wavell to achieve that end. Beginning in December 1946, British officials began looking for a viceregal successor to Wavell, and soon fixed on Admiral Lord Mountbatten of Burma, a war leader popular among Conservatives as the great-grandson of Queen Victoria and among Labour for his political views.

Mountbatten and independence

Lord Louis Mountbatten and his wife Edwina Mountbatten with Jinnah in 1947

Main articles: Partition of India and Pakistan Movement

On 20 February 1947, Attlee announced Mountbatten's appointment, and that Britain would transfer power in India not later than June 1948.[148] Mountbatten took office as Viceroy on 24 March 1947, two days after his arrival in India.[149] By then, the Congress had come around to the idea of partition. Nehru stated in 1960, "the truth is that we were tired men and we were getting on in years ... The plan for partition offered a way out and we took it."[150] Leaders of the Congress decided that having loosely tied Muslim-majority provinces as part of a future India was not worth the loss of the powerful government at the centre which they desired.[151] However, the Congress insisted that if Pakistan were to become independent, Bengal and Punjab would have to be divided.[152]

Mountbatten had been warned in his briefing papers that Jinnah would be his "toughest customer" who had proved a chronic nuisance because "no one in this country [India] had so far gotten into Jinnah's mind".[153] The men met over six days beginning on 5 April. The sessions began lightly when Jinnah, photographed between Louis and Edwina Mountbatten, quipped "A rose between two thorns" which the Viceroy took, perhaps gratuitously, as evidence that the Muslim leader had pre-planned his joke but had expected the vicereine to stand in the middle.[154] Mountbatten was not favourably impressed with Jinnah, repeatedly expressing frustration to his staff about Jinnah's insistence on Pakistan in the face of all argument.[155]

Mountbatten meets Jinnah, Nehru and other leaders to plan the Partition of India

Jinnah feared that at the end of the British presence in the subcontinent, they would turn control over to the Congress-dominated constituent assembly, putting Muslims at a disadvantage in attempting to win autonomy. He demanded that Mountbatten divide the army prior to independence, which would take at least a year. Mountbatten had hoped that the post-independence arrangements would include a common defence force, but Jinnah saw it as essential that a sovereign state should have its own forces. Mountbatten met with Liaquat the day of his final session with Jinnah, and concluded, as he told Attlee and the Cabinet in May, that "it had become clear that the Muslim League would resort to arms if Pakistan in some form were not conceded."[156][157] The Viceroy was also influenced by negative Muslim reaction to the constitutional report of the assembly, which envisioned broad powers for the post-independence central government.[158]

On 2 June 1947, the final plan was given by the Viceroy to Indian leaders: on 15 August, the British would turn over power to two dominions. The provinces would vote on whether to continue in the existing constituent assembly or to have a new one, that is, to join Pakistan. Bengal and Punjab would also vote, both on the question of which assembly to join, and on the partition. A boundary commission would determine the final lines in the partitioned provinces. Plebiscites would take place in the North-West Frontier Province (which did not have a League government despite an overwhelmingly Muslim population), and in the majority-Muslim Sylhet district of Assam, adjacent to eastern Bengal. On 3 June, Mountbatten, Nehru, Jinnah and Sikh leader Baldev Singh made the formal announcement by radio.[159][160][161] Jinnah concluded his address with "Pakistan Zindabad" (Long live Pakistan), which was not in the script.[162] Some listeners misunderstood his Urdu as "Pakistan's in the bag!".[163] In the weeks which followed Punjab and Bengal cast the votes which resulted in partition. Sylhet and the N.W.F.P. voted to cast their lots with Pakistan, a decision joined by the assemblies in Sind and Baluchistan.[161]

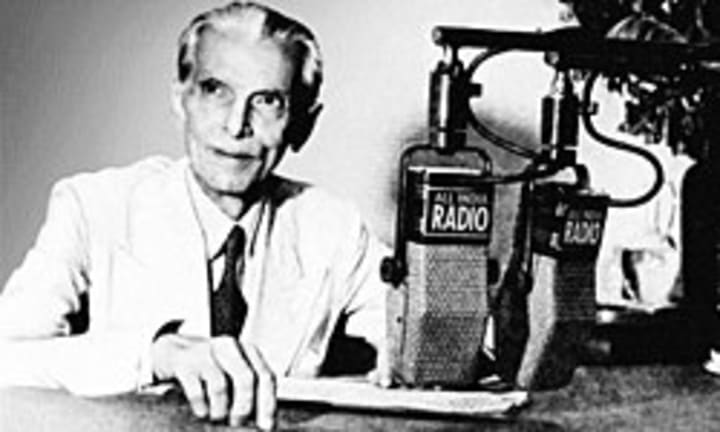

Jinnah announcing the creation of Pakistan over All India Radio on 3 June 1947

On 4 July 1947, Liaquat asked Mountbatten on Jinnah's behalf to recommend to the British king, George VI, that Jinnah be appointed Pakistan's first governor-general. This request angered Mountbatten, who had hoped to have that position in both dominions—he would be India's first post-independence governor-general—but Jinnah felt that Mountbatten would be likely to favour the new Hindu-majority state because of his closeness to Nehru. In addition, the governor-general would initially be a powerful figure, and Jinnah did not trust anyone else to take that office. Although the Boundary Commission, led by British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe, had not yet reported, there were already massive movements of populations between the nations-to-be, as well as sectarian violence. Jinnah arranged to sell his house in Bombay and procured a new one in Karachi. On 7 August, Jinnah, with his sister and close staff, flew from Delhi to Karachi in Mountbatten's plane, and as the plane taxied, he was heard to murmur, "That's the end of that."[164][165][166] On 11 August, he presided over the new constituent assembly for Pakistan at Karachi, and addressed them, "You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan ... You may belong to any religion or caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the State ... I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State."[167] On 14 August, Pakistan became independent; Jinnah led the celebrations in Karachi. One observer wrote, "here indeed is Pakistan's King Emperor, Archbishop of Canterbury, Speaker and Prime Minister concentrated into one formidable Quaid-e-Azam."

If you guys want third part then comment

THE PART TWO(2)

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.