Andromeda was the princess of Aethiopia and the wife of Perseus. Together, they founded Mycenae – the city after which the entire Mycenaean Age was named – and the Perseid Dynasty, making her the ancestress of Heracles, Castor and Pollux, Helen of Troy, and countless others.

Between Andromeda’s iconic rescue from certain death – more on that momentarily – her famous husband, and her famous descendants, it’s unsurprising that Andromeda proved a fertile muse for artists. It’s also unsurprising and unfortunate that Andromeda has been whitewashed by many of those same artists for thousands of years.

Aethiopia Again

I discuss the meaning and evolution of the Greek exonym ‘Aethiopia’ at length in my piece on Memnon (here). In short, it started out as a catch-all term the Greeks used for lands where the people were darker-skinned than they were, but this term was narrowed down to refer to the Nubian Kingdom of Kush by the time Herodotus wrote his Histories in 430 BC. This narrower definition of the term is almost certainly how later Roman writers like Ovid and Hyginus would have understood ‘Aethiopia’.

With that out of the way, let’s take a brief look at the sources.

Greek Attestations

(8th Century BC) Hesiod briefly mentions Perseus by name, referencing his slaying of the Gorgon but not his later rescue of Andromeda.

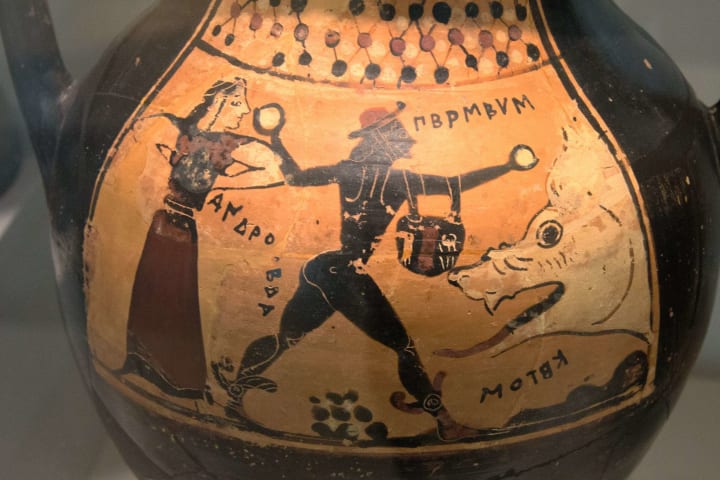

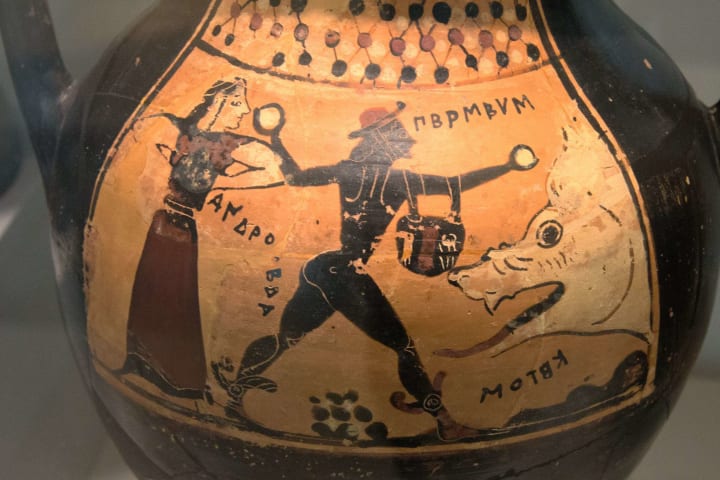

(6th – 5th Century BC) Scenes depicting Perseus defending Andromeda from Cetus appear on amphorae and vases.

(5th Century BC) Sophocles and Euripides both write plays titled Andromeda, of which only fragments remain. According to the surviving fragments of Euripides’ work, Andromeda is the daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia of Aethiopia, who have offended Poseidon in some unspecified way. Andromeda’s parents have chained her to a rock near the sea as a sacrifice to appease Poseidon’s wrath, and it is in this state that Perseus finds her. Perseus at first mistakes Andromeda for a statue – more on that later – but quickly realizes his mistake and is smitten by her beauty. Perseus then defeats the sea monster and insists on marrying Andromeda.

Herodotus also writes in Book 7 of his Histories that King Xerxes of the Persian Achaemenid Empire once tried to sway the Argives to his side of the Greco-Persian Wars by citing Andromeda as their common ancestor through her son Perses.

Roman Attestations

(1st Century AD) Ovid’s Metamorphoses seems to be the first place where Andromeda’s beauty is established as the reason for her plight, otherwise his account of her rescue follows the narratives set forth by his Greek predecessors. Meanwhile, in Hyginus’ Fabulae, Cassiopeia boasts that Andromeda is more beautiful than all of the oceanic nymphs, offending Poseidon and leading to Andromeda’s peril.

While Ovid echoes Euripides in writing that Perseus initially mistook Andromeda for a marble statue, he also makes it clear elsewhere in his Heriodes and Ars Amatoria that he imagined Andromeda to be dark-skinned.

So why did nearly all ancient and Renaissance art of Andromeda depict her as a white woman?

The Marble Excuse

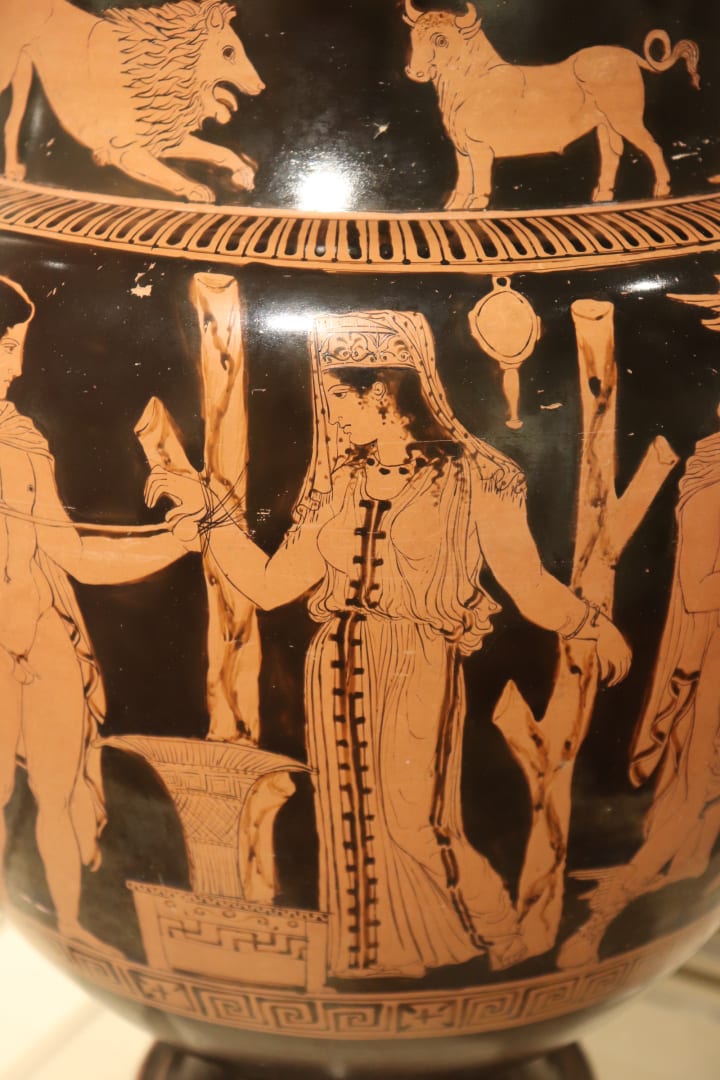

Many scholars and casual observers have pointed to the common thread of Andromeda being mistaken for marble as proof of her pale complexion. There are three problems with this argument. Firstly, we now know that the white marble statues we associate with Classical Greece and Rome were originally painted – sometimes quite garishly. Secondly, these statues are also marble:

Thirdly, we’ve already established that one of the sources for the Andromeda-as-marble metaphor clearly understood Andromeda to be dark-skinned.

What About the Pottery?

Yes, some of the Ancient Greek pottery seems to show a pale Andromeda. Let’s look at this hydria depicting Perseus:

Let's now compare it to the amphora depicting Perseus and Andromeda we discussed earlier.

Either we have to recognize that the Ancient Greeks did not use color in a literal, descriptive fashion on their pottery, or we must come up with a plausible explanation as to why Perseus is occasionally depicted as a black man.

Roman Beauty Standards and Whitewashing

Let’s circle back to Ovid. While Ovid confirms that Andromeda was both dark-skinned and beautiful, he also seems to have recognized that this was a controversial take at the time. Yes, in his Heriodes Ovid has Sappho holding up Andromeda as an example of dark skin being beautiful, but she seems to be doing so in response to a complaint Phaon – the object of her affection – has made about her complexion. Yes, in Book II of his treatise on romance, the Ars Amatoria, he says that Andromeda’s “dark complexion was not criticized by Perseus”, but he does so in a section entitled “Don’t Mention Her Faults” and follows up by instructing men to grow “accustomed to what’s called bad, you’ll call it good[.]”

Ovid’s works, when taken in full context, seem to suggest that there was an ongoing debate at the time as to whether beauty and dark skin were mutually exclusive. The most generous reading of the Ars Amatoria is that Ovid was advising his fellow Romans against reflexively recoiling at the unfamiliar. Unfortunately, it seems that his contemporaries and subsequent generations were disinclined to listen to Ovid – at least on this matter.

Seemingly unable or unwilling to reconcile with the idea of a Greek hero marrying a beautiful dark-skinned woman, within a century we have the Greco-Roman writer Philostratus describing Andromeda as being “fair of skin though in Ethiopia” in contrast with the other “Ethiopians with their strange coloring and their grim smiles.” Around the same time, Heliodorus of Emesa adds to this tradition of the white Ethiopian with his account of Queen Persinna of Aethiopia, who gives birth to a white child as a result of staring at a painting of Andromeda in her palace.

Some Political Explanations

As I mentioned in my piece on Memnon, the newly formed Roman Empire fought a brief war against the Nubian Kingdom of Kush in the early 20s BC. In the end, Caesar Augustus was forced to sign a peace treaty with Kandake Amanirenas which included reparations for any tributes levied during Roman occupation of Kushite territories. Perhaps the ill-will the Romans might have felt toward the black woman who had successfully resisted their conquering armies, compounded with their lingering antipathy toward Cleopatra for her perceived role in the civil war between Augustus and Marc Antony, contributed to the Roman rejection of Andromeda’s dark complexion.

Another theory comes to us courtesy of the First Jewish-Roman War, fought between 66-73 CE. Writing just two years after the war’s conclusion, Judeo-Roman historian Flavius Josephus asserted in The Jewish War that the site of Andromeda’s rescue was a rock off the coast of Jaffa. It’s important to note that Flavius Josephus went from being a general fighting against the Roman army, to being Emperor Vespasian’s captured interpreter, before finally serving as advisor and chronicler Vespasian’s son, the future Emperor Titus. Relocating Andromeda to Jaffa was likely a strategic decision on the part of Josephus and his imperial patrons, aimed at connecting their freshly conquered province to the greater Greco-Roman world.

Interestingly, none of the Roman attempts to link Andromeda to the formerly Persian world – at least, none that I could find – make use of Herodotus’ anecdote about Xerxes and the Argives. Ancient Greek sources concerning Andromeda’s son Perses, the supposed ancestor of the Persians, are also pretty thin on the ground. It may be that the Greeks considered this connection between Andromeda and the Persians to have been a convenient fabrication on the part of Xerxes. Certainly, its easy to imagine Xerxes using the Greek tendency to insert their heroes into the royal lineages of their contemporaries as a tool to sway the Argivians to their side – evidently to great effect, as Argos ended up siding with the Persians during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece.

Perhaps the Romans were holding the Andromeda-Persia connection in reserve, to be deployed in the event that they ever succeeded in conquering Parthian – and later Sassanid – Persia. As the Roman Empire never did succeeded in conquering Persia, Nubia, or the region that would later come to be known as Ethiopia, Roman writers and artists might have found highlighting Andromeda’s connections to those regions inconvenient.

The Colonial Era to the Modern Day: Conclusions

It should come as no surprise that European artists during the height of the colonial era (1500s – late 1800s) seized on the ‘marble excuse’, and the Roman innovation of the ‘magically white Ethiopian’, to paint Andromeda as being extremely white. Given Hollywood’s long and storied history of whitewashing history and myth, it should also come as no shock that Andromeda has been portrayed in film by white actresses as recently as 2012.

So, what conclusions can we draw from this exploration of Andromeda’s origins and interpretation over the centuries?

Firstly, the long-held assumption that the Roman Empire was a pre-colorist society merits re-examination. The conflicting works of Ovid and his contemporaries suggest that the early Roman Empire may have been a society that was grappling with existing colorist beauty standards – or developing new ones – at the same time it was settling its border with an African power and waging war against a Middle-Eastern one.

Secondly, Andromeda was definitely not originally conceived of as a white woman. Our earliest written sources defining Andromeda as a princess of Aethiopia were written right around the same time Herodotus was busy identifying Aethiopia with Nubia. Even if one wants to argue that Andromeda’s Aethiopia was not Nubia, but in fact ancient Judea or some other coastal part of Persia, we are still left with the Ancient Greeks’ literal definition of Aethiopa: the land of ‘burnt faces’.

Somehow, I don’t think that Euripides and Sophocles imagined Andromeda to be the princess of a bunch of sun-burned, peeling white people – certainly, Ovid didn’t think so. Even those of Ovid’s contemporaries who pushed the nonsensical idea of Andromeda’s whiteness acknowledged that the nation she hailed from was inhabited by dark-skinned people.

So, if Hollywood wants to continue casting Andromeda as a white woman, they should be required to explicitly state her background as a princess of Aethiopia – just so the audience can properly digest the racist lunacy of the notion.

Or, or, they could cast a black or brown woman for the role of Andromeda.

About the Creator

T. A. Bres

A writer and aspiring author hoping to build an audience by filling this page with short stories, video game reviews/rants, history infodumps, and comparative mythology conspiracy theories.

Come find me @tabrescia.bsky.social

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.