Earthquakes did not produce the largest tsunamis in Earth's history.

When tsunamis are caused by ear

Some of the most catastrophic tsunami waves in recorded history are caused by landslides that unexpectedly collapse down mountains into water rather than the ground trembling.

According to recent worldwide data, these occurrences can raise sea walls significantly higher than the majority of earthquake-driven tsunamis, frequently hitting locations with little time to respond.

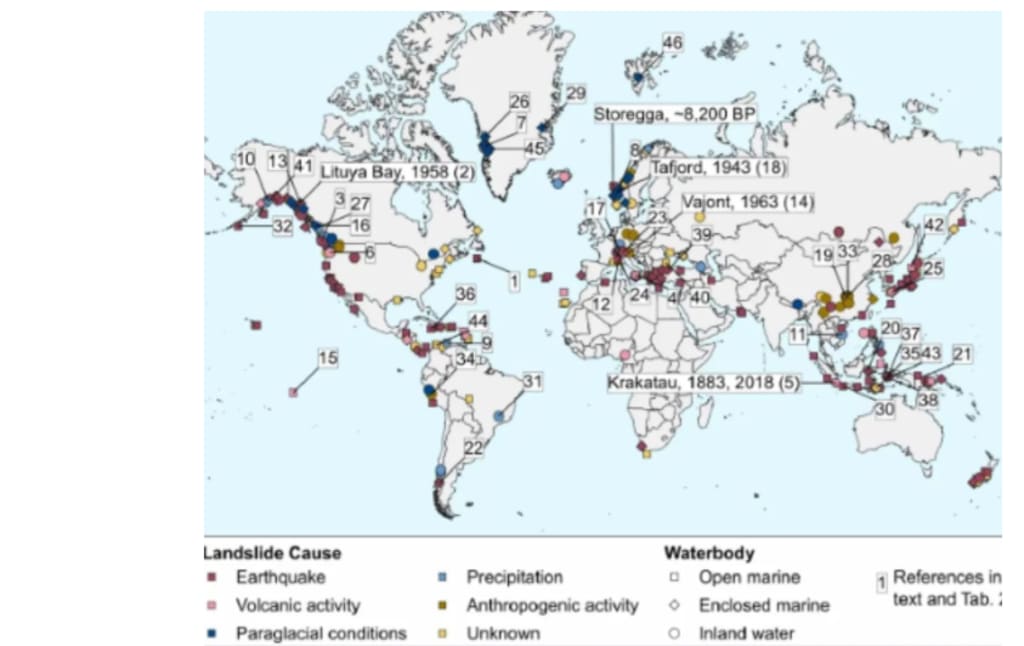

The discovery is based on a global catalogue that looked at 317 recorded landslide-induced tsunamis and tracked the locations of the biggest waves in fjords, coastal inlets, and inland reservoirs.

Where the slide strikes the water, a landslide-triggered tsunami—a wave created when shifting ground pushes water aside—begins.

Katrin Dohmen, who investigates coastal hazards at Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin), oversaw the project. In order to understand how basin geometry affects final wave height, her team compared locations, triggers, and wave heights.

Landslip tsunami history

Because there is nowhere wide for the water to spread, narrow fjords, small bays, and reservoirs can create extremely high waves. When waves are confined in basins between adjacent coastlines in enclosed marine environments, energy remains trapped and the crest rises closer to humans.

The worst heights can rapidly diminish as a wave leaves the basin because the same topography restricts long-distance migration. The stains and shattered plants that a tsunami leaves on buildings and slopes are frequently used by field teams to gauge its size.

Because it captures inland reach, scientists refer to the highest mark run-up as the highest point water reaches on land. Although misunderstanding can be lessened by using run-up and nearshore water height, many historical events are still difficult to compare due to missing measurements.

The document that everyone references

The largest run-up ever measured for a wave event occurred in 1958 when a landslip into Lituya Bay, Alaska, caused it to reach over 1,720 feet.

In a matter of seconds, the sliding rock struck the little entrance and pushed water upstream, removing trees from a hillside and leaving a distinct trimline that is still discernible today.

At the bay mouth, about 7.5 miles away, the wave was closer to 30 feet, exhibiting rapid decline as energy dispersed, water depth rose, and the surge left the small basin.

When tsunamis are caused by earthquakes

Underwater sediment and coastal cliffs may be shaken loose by ground shaking, resulting in a wave on top of the tsunami that the earthquake initiates.

The largest waves typically require a slide in confined spaces, although the catalogue indicates that earthquakes and volcano collapses cause the heaviest damage.

Because an earthquake warning could overlook a neighbouring landslip wave that arrives earlier than anticipated, this poses a forecasting challenge. Rock and ash can be dumped into the sea in a matter of minutes when unstable volcanic slopes suddenly collapse.

The force of that moving mass causes the water's surface to rise as it arrives, and the initial surge may swiftly reach neighbouring shorelines. Emergency planning for island volcanoes must address abrupt waves as a distinct risk since eruptions and collapses might coincide.

Tsunamis caused by landslides and ice melt

Steep rock walls may become unsupported due to glacier loss, and when the ice that originally kept them in place thins, fissures may widen. This landscape modification following glacier retreat is known to researchers as paraglacial conditions, and it can prepare slopes for collapse.

Long after the original impact, a Greenland rock slide in 2023 caused a 656-foot tsunami and a nine-day water oscillation that reverberated through a narrow fjord, continually churning water back and forth.

Rain can make slopes weaker.

Extra water weight increases the likelihood that a hillside may begin to slide, and heavy rain soaks soil and cracked rock.

Gravity may be able to overcome the strength of the slope due to rising pore water pressure, which is water pressure within the soil that lowers friction. That mechanism can transform a storm into an abrupt wave with little time to manoeuvre in small valleys and river reservoirs.

Waves can be caused by humans.

Because shifting water levels also affect groundwater levels in the banks, reservoir draw downs and refilling can put adjacent slopes under stress.

Uneven water pressure can cause cracks to emerge and friction to decrease along weak layers as the bank drains or saturates, resulting in a slide.

The catalogue connects these human decisions to the largest inland-water waves, which is significant for dam operators. Scientists must search for bottom clues rather than eyewitness accounts since many offshore landslides do not leave any surface scars.

Fresh slump blocks and tracks that are missed by low detail can be found using high-resolution bathymetry, which are maps of underwater depth and shape. The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO), a widely used public basemap, is frequently too coarse for minor errors.

Why it's important to resolve this

Since most underwater slides that cause tsunamis are smaller than 0.24 cubic miles, they can be smoothed away with a coarse grid.

There are a lot of slide scars because GEBCO uses a 15 arc-second spacing, or roughly 1,500 feet at the equator. Although many coasts are still uncovered, finer surveys go beyond GEBCO and feed susceptibility mapping, which rank predicted failure spots.

There may be a few seconds of warning time.

Because the source is located directly offshore or above the nearest beach, nearshore landslip waves can reach there in less than two minutes.

Officials seldom have time to issue a warning since nearshore landslip waves can reach the nearest beach in less than two minutes.

The best opportunity occurs when a slope is recognised to be unstable, allowing sensors to send out alerts before movement becomes rapid.

Monitoring tsunamis and landslides

Even when coastal gauges remain silent, bottom pressure sensors in the open ocean can identify passing tsunamis.

Deep-ocean buoys called DART are used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to measure changes in pressure, and the network helps identify tsunamis.

Modellers can improve forecasts with the use of DART data, but residents facing a wave generated directly at the shoreline cannot benefit.

When combined, the TU Berlin catalogue shows why, even in cases when an earthquake is the initiating event, fjords and reservoirs can reach record heights.

While DART data, more intelligent local monitoring, and improved seafloor maps can reduce uncertainty, most towns still require quick self-evacuation strategies.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.