Early Hominids Ate Just About Everything: The Real Paleo Diet

Today, very few individuals truly lead a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and Paleo diets probably oversimplify what was available thousands of years ago.

Simplicity and excessive neatness are prone to creep into reconstructions of human evolution. For instance, our ancestors might have stood on two legs to survey a field of tall grass or might have started speaking when they finally had something to say. The hypothetical food of our ancestors has also been oversimplified, much like the majority of our knowledge of early hominid behaviour.

Consider the popular Paleo diet, which takes cues from lifestyle choices made by people between 2.6 million and 10,000 years ago during the Palaeolithic or Stone Age. It exhorts followers to abandon the products of contemporary culinary advancement, such as dairy, farm products, and processed foods, and adopt a pseudo-hunter-gatherer lifestyle, similar to that of Lon Chaney Jr. in the movie One Million BC.

Adherents advise following a fairly strict "ancestral" diet that contains recommended amounts of carbs, proteins, and lipids as well as recommended levels of physical activity. These recommendations are primarily based on observations of contemporary people who lead at least a partially hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

But from a scientific perspective, these kinds of straightforward descriptions of the behaviour of our ancestors typically don't add up. The development of hominid food is a critical subject in the history of human behaviour, and C. Owen Lovejoy and I recently examined it in depth. Between between 6 and 1.6 million years ago, before and after the first use of altered stone tools, we concentrated on the early stage of hominid evolution.

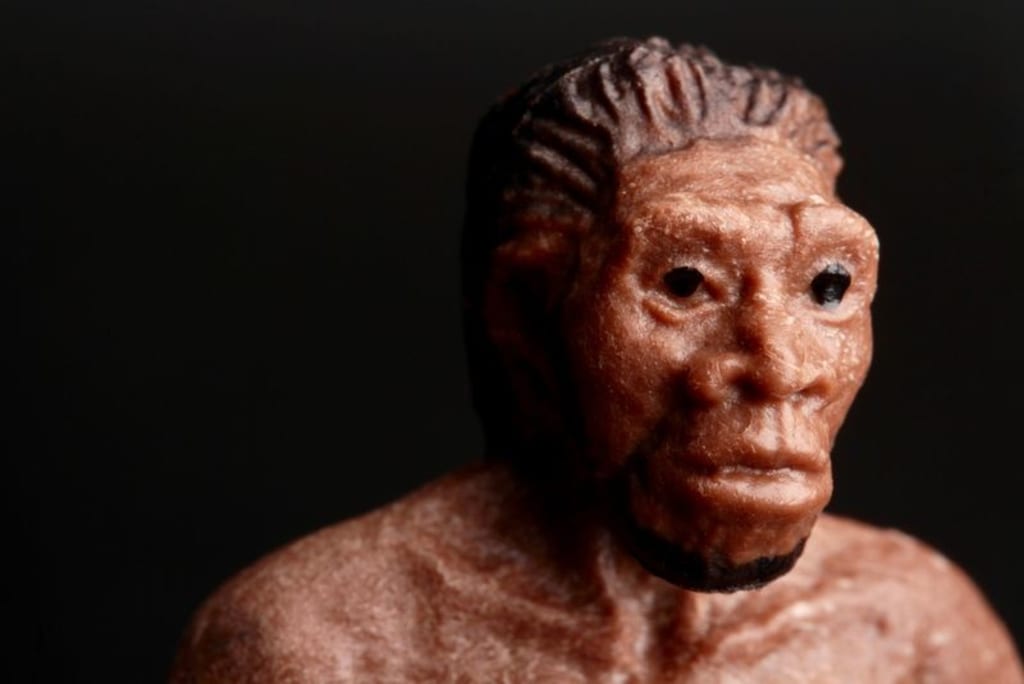

The earliest members of our own genus, the relatively intelligent Homo, as well as the hominids Ardipithecus and Australopithecus, are all represented in this time period. None of these were the much later, modern humans, but rather our ancient ancestors.

We carefully investigated the foraging behaviour of extant animals as well as the fossil, chemical, and archaeological evidence. Why is this important? Even an hour spent observing animals in the wild will reveal the quick solution: practically everything an organism does on a daily basis is just connected to remaining alive. This includes actions like feeding, fending off predators, and preparing for reproduction. That is how evolution works.

What exactly did our forefathers eat? In some instances, researchers can use cutting-edge technology to investigate the issue. To determine the proportions of meals the hominids consumed that were derived from woody plants (or the animals that ate them) vs open country plants, researchers analyse the chemical composition of ancient tooth enamel.

Other researchers search ancient dental tartar for fragments of silica from plants that can be categorised, such as fruit from a certain plant family. Others look closely at the tiny cuts left by stone tools as they butcher bones. Researchers have discovered, for instance, that hominids were consuming antelope meat and bone marrow as early as 2.6 million years ago. Whether these antelopes were hunted or scavenged is widely contested.

Although these methods are instructive, they ultimately only provide a murky picture of diet. They offer solid proof that early hominids consumed leaves, bark, sedges, fruits, invertebrate and vertebrate creatures, subterranean storage organs of plants (like tubers), and other foods. However, they do not provide us with information on the relative significance of different foods. Furthermore, these methods fail to explain what distinguishes hominids from other primates because all of these items are consumed by live monkeys and apes on occasion.

So what should we do from here? According to my colleague Lovejoy, in order to create a human, the same principles that apply to beavers must be applied. To put it another way, you need to study the "rules" of foraging. We aren't the first scientists to experiment with this. George Bartholomew and Joseph Birdsell, anthropologists, made an attempt to characterise the ecosystem of early hominids in 1953 by using broad biological principles.

Fortunately, these guidelines have been compiled over time by ecologists in a field of study known as optimal foraging theory (OFT). OFT makes predictions about the foraging behaviour of several animals based on straightforward mathematical models.

For instance, one traditional OFT model determines which resources should be consumed and which ones should be avoided given a collection of prospective foods with estimated energy value, abundance, and handling time (how long it takes to obtain and consume).

One hypothesis, or sort of "golden rule" of foraging, states that an animal should specialise in profitable items (those high in energy and low in handling time) when they are plentiful, but widen its diet when they are scarce.

In general, data from living things that are as dissimilar as insects and contemporary people agree with such expectations. heavy-altitude grey langur monkeys avoid specific types of roots, bark, and leathery mature evergreen leaves in the Nepal Himalayas because they are all calorie-deficient, heavy in fibre, and require a lot of handling time.

However, during the bleak winter, when better meals are scarce or unavailable, they will ravenously consume them.

In a different, more controlled experiment, when chimpanzees are shown different amounts of almonds in or out of the shell, they later find the larger amounts (using more energy), the closer-located ones (requiring less time to pursue), and the shellless ones (requiring less time to process).

They do not find the smaller, farther-located or "with-shell" nuts. This shows that at least some animals may remember the best foraging strategies and apply them even when the food is far away and beyond their immediate field of view. Key hypotheses from OFT are supported by both of these studies.

One might be able to forecast the diet of specific hominids who lived in the distant past if they could assess the characteristics crucial to foraging. Although it seems frightening, the process of human evolution was never intended to be simple.

The OFT method compels the study of how and why animals use certain resources, which leads to a more careful analysis of early hominid ecology. A few scientists have successfully used OFT, most notably in the excavation of relatively recent hominids like Neandertals and anatomically modern humans.

However, a few daring individuals have investigated earlier human nutritional histories. One team, for instance, estimated the expected ideal diet of Australopithecus boisei using OFT, present equivalent habitats, and information from the fossil record.

The infamous "Nutcracker Man" who lived in East Africa over 2 million years ago is that one. Based on factors like habitat or the usage of digging sticks, the research shows a large variety of potential foods, widely variable mobility patterns, and the seasonal importance of specific resources, like roots and tubers, for satisfying anticipated caloric needs.

In 1980, scientists Tom Hatley and John Kappelman observed that hominids had several traits with bears and pigs, including bunodont, or low, rounded cusp, back teeth.

If you have ever observed these animals foraging, you are aware that they will consume almost everything, including tubers, fruits, leafy plants and twigs, insects, honey, and vertebrate animals that have been either scavenged or hunted.

The energy value of particular foods in particular habitats at particular times of the year will determine (you got it) the proportion contribution of each food type to the diet. The entire history of human evolution provides evidence that both our ancient ancestors and modern humans are omnivorous.

The notion that our more distant ancestors were excellent hunters is also probably untrue because bipedality is a terrible method to hunt, at least prior to the development of advanced cognition and technology. We have a smaller range of motion than pigs and bears.

The fastest person on the planet cannot outrun the average rabbit, according to anthropologist Bruce Latimer. Another justification for being flexible with food.

Simple descriptions of hominin ecology are disconnected from the true, amazing richness of our shared past. One recent extension of an old necessity is the recent inclusion of pastoral and agricultural items in many modern human diets, for which we have quickly acquired physiological adaptations.

By employing just one foraging technique or sticking to a specific ratio of carbs, proteins, and fats, hominids did not first spread throughout Africa, then the entire planet.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.