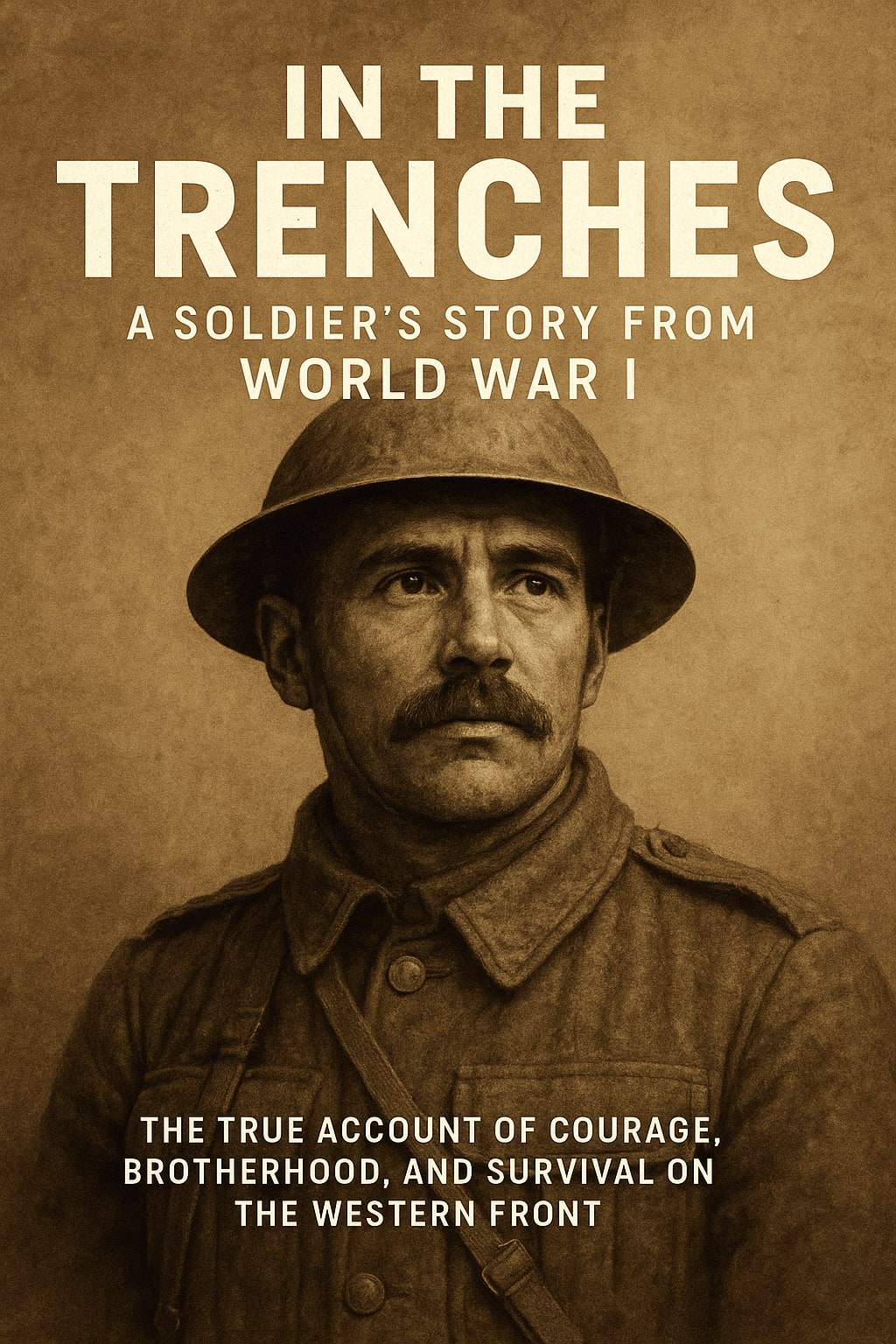

A Biography from the First World War

The True Account of Courage, Brotherhood, and Survival on the Western Front

I never imagined that the muddy trench lines stretching across France would become the boundaries of my world for nearly four years. I was just eighteen when I left home, a fresh-faced boy from Yorkshire with dreams of honor and adventure, not knowing the price that awaited those who believed the war would be over by Christmas. The letter came in June 1915, marked with the king’s seal, summoning me to service. I still remember my mother’s trembling hands as she packed my small case, hiding her fear behind a hopeful smile. My father, a Boer War veteran, shook my hand silently, pride and dread battling behind his eyes. We all knew the war was nothing like what the papers claimed, but we pretended anyway. By August, I was in uniform, standing in formation with hundreds of others, all of us still clinging to the illusion that bravery would be enough. We trained in the cold mornings and marched through the twilight, singing songs to drown out the gnawing uncertainty. By October, I was shipped to the Western Front, assigned to the 11th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment—what they called a “Pal’s Battalion,” since many of us came from the same town. That was both a blessing and a curse. When your mates fell beside you, it wasn’t just fellow soldiers you lost—it was childhood friends, neighbors, brothers.

The first time I set foot in the trenches, the stench struck me harder than any gunfire ever could. Rotting sandbags, latrines overflowing, corpses half-buried in the mud—the air was thick with decay, fear, and resignation. Our trench was barely more than a zigzagged ditch carved into the Flanders soil, lined with duckboards to keep our boots from sinking into the endless muck. Rats as large as cats scurried freely, fat from feeding on the fallen, and lice tormented us nightly. But worst of all was the shelling. When the artillery began—whether from our side or theirs—the earth itself seemed to erupt. The sky would flash, and the thunder would roar, shaking the trench walls and showering us with dirt and shrapnel. There was no warning, no safe hour. Sleep came in snatches, and food was whatever stale biscuit or tinned meat could be eaten between attacks. Letters from home became our only real connection to sanity. I clung to every word my sister wrote, reading and rereading the same sentences by candlelight while bombs fell in the distance. Her words were my anchor, her steady script reminding me that there was a world beyond the wire.

In our battalion, we had formed a tight circle of friends—Tommy from Salford, who could whistle any tune; Jacobs, a Jewish lad from London with a heart as big as his laugh; and Evans, a quiet Welshman who carried a Bible in one pocket and a photo of his wife in the other. These men became my brothers. We huddled together in the cold, we shared stories and cigarettes, and we watched each other’s backs. When we went “over the top”—the terrifying climb out of the trench into No Man’s Land—it was their faces I looked for. No Man’s Land was a nightmare of craters, barbed wire, and broken bodies, a place where death could come from a sniper’s bullet or an unseen tripwire. I remember one morning in July 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, when our unit was ordered to charge. The whistle blew, and we surged forward into a hail of machine gun fire. I saw Evans fall, a red bloom on his chest, but I couldn’t stop. The screams, the explosions, the mud—it all blurred into chaos. I reached the enemy trench only to find it empty, and then the counterattack came. We held them off with bayonets and grenades, fighting like animals. When it was over, the sun rose on a field soaked in blood. Out of our company of 150, only 32 returned to the trench. I never saw Evans again. Jacobs was wounded and sent home, and Tommy, miraculously unscathed, never smiled again.

We learned to live with death like a constant shadow. Gas attacks became frequent, the yellow-green mist rolling in without warning. Our masks were our lifelines, and even then, many didn’t survive. Once, a shell hit a nearby dugout, and I spent hours digging through the rubble to find survivors. I pulled out a corporal whose legs had been crushed. He didn’t make it. The horror etched itself into our eyes. We all became older than our years. Yet, amid the despair, there were flickers of humanity. On Christmas Eve, 1916, a temporary ceasefire was called, and both sides sang carols across the lines. Some brave souls even met in the middle, exchanging cigarettes and shaking hands. I still have a button a German soldier gave me. We never saw each other again, but in that moment, we were just men, not enemies.

By the time the war ended in 1918, I was 22, but I felt 50. I had survived three years of hell, two injuries, and the loss of nearly everyone I had called friend. When the armistice was signed, we didn’t cheer. We sat in silence, letting the weight of it all settle in. The trenches were abandoned, the rifles laid down, and the war that was supposed to end all wars left behind millions of graves and a generation forever changed. I returned home to find the streets quieter, the houses darker, and the people more distant. Some didn’t recognize me, and I barely recognized myself. I tried to speak of what happened, but words failed. Only the quiet nods of other veterans, the flicker of understanding in their eyes, reminded me that I wasn’t alone.

This story, my story, isn’t just about fighting. It’s about courage born from desperation, brotherhood forged in terror, and the will to survive when all hope seems lost. It’s for those who never came back and those who returned as shadows of themselves. It’s a remembrance of mud and blood, of loyalty and loss, of boys who went to war and never became men. And it is a promise—one soldier’s promise—to never let the world forget what was endured in those trenches.

About the Creator

Irshad Abbasi

Ali ibn Abi Talib (RA) said 📚

“Knowledge is better than wealth, because knowledge protects you, while you have to protect wealth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.