The Rise of Jewish-American Comedy During the Holocaust

Notes from a Novelist

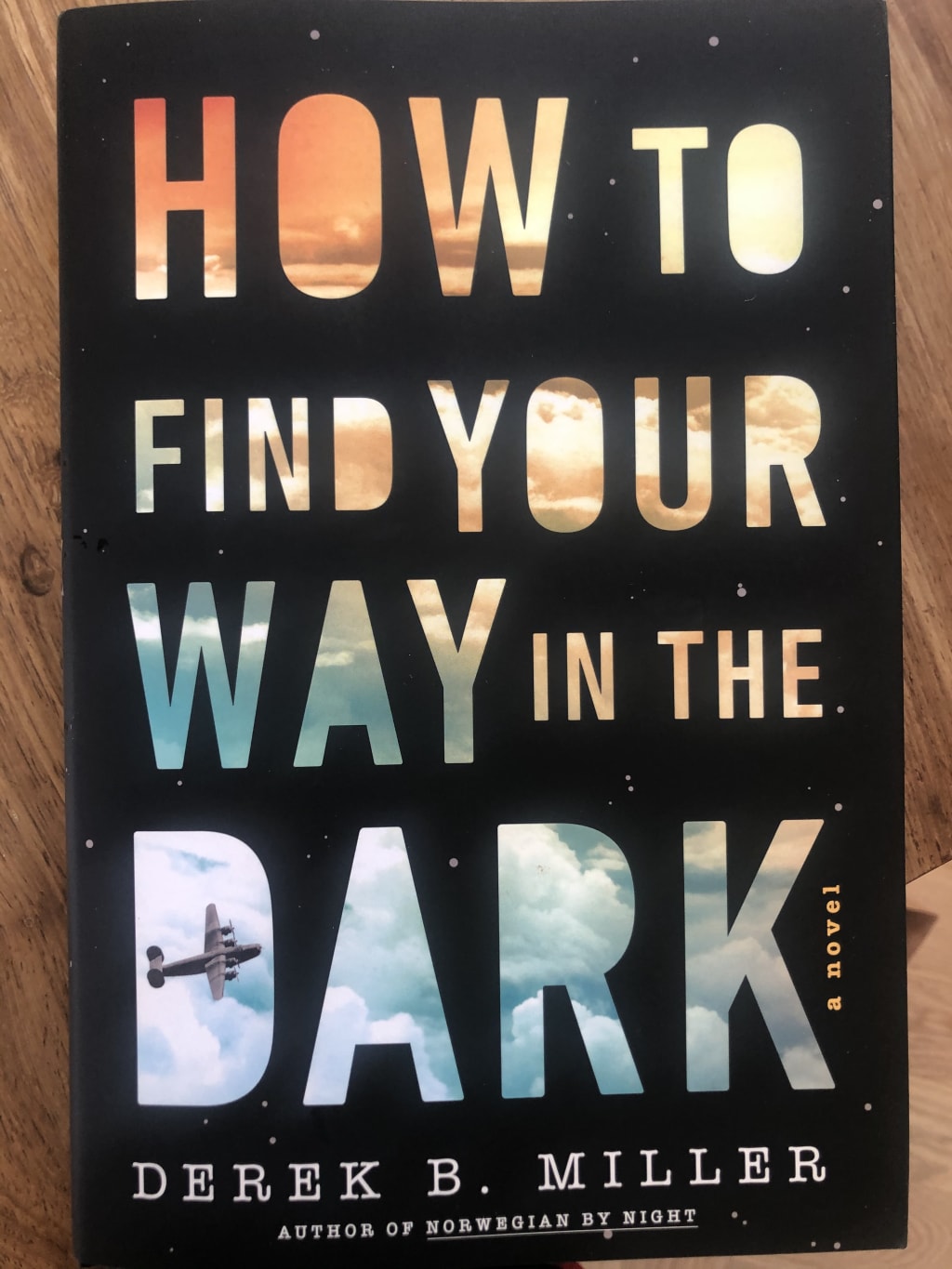

I wrote a novel called How to Find Your Way in the Dark. The book became a 2021 Best Mystery Novel by The New York Times and also a 2021 National Jewish Book Award Finalist. While writing it I observed something. It was something big: an observation about a unique and influential human experience that, if we pay closer attention to it, might help us understand more about who we are and what it means to be alive.

How big?

About as big as the Atlantic Ocean.

How can people fail to see something as big as the Atlantic ocean?

As it happens there are answers to this. In my view, there are a number of ways: Distance (it’s too far away in time or space); Direction (we’re looking the wrong way — literally or metaphorically); Distraction (our focus prevents us from seeing the unexpected); Dissonance (our brains reject the disharmonious); and Indifference (to notice something … we have to care). This is my personal list.

Still, here’s what I noticed. The rise of Jewish-American comedy — which would impact every aspect of mass media comedy across the world by the 1960s — reached its maturity in form and practice in the Catskills of New York while the Holocaust was raging in Europe.

In one way, this is a simple fact. It invites a shrug. But what makes it a fact of intellectual and philosophical enormity is that the Jewish world was laughing its greatest laughter while crying it deepest tears at precisely the same moment and those in the West knew about those those in the East. In casting my mind around the globe and through time, I can't evoke a more dramatic, consequential, radically juxtaposed, world-changing couplet of events as the attempted annihilation and genocide of an entire people in one region while those safely in another were perfecting a new form of happiness so delightful it would define entertainment across the planet for all foreseeable future. And I’m not being histrionic: The stand-up comedy of Zimbabwe, circa 2021, came from the Catskills as directly as the hip-hop of Pakistan came from the Bronx. And the reason we have informed consent and the entire post-war Liberal order is because of WWII and the Holocaust.

On the one hand, there’s the history of Jewish-American comedy and everything Seinfeld talks about in Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. On the other, there’s Holocaust studies. What I don’t see is anyone pulling these parts together into a single, coherent story of radical juxtaposition let alone risking interpretation and analysis. If they did, there would be treasure to be uncovered, and you don’t have to be Jewish to care. For example: How on earth did that happen? How could people in the Catskills keep their sense of humor at a time like that? Or was it a reaction to the times? Or were they aloof and emotionally distant? Was it an example of American exceptionalism, or was the Jewish community acting in a way unique to itself? Is this kind of dissociative behavior seen in other communities under stress? Were the themes and subjects and topics of the humour influenced by the darkness of events in Europe? In a word: What the hell was going on?

It isn’t like no one could be asking these questions. I came across the peer reviewed journal HUMOR (in capital letters, yes really, and no it's not an acronym): the International Journal of Humor Research, which covers such diverse and inadvertently-hilarious topics as interdisciplinary humor research; humor theory; empirical studies in humor, laughter, comedy and related fields from around the world and, (my personal favorite because it promises off-kilter metal skull caps, electrodes and lab coats) humor research methodologies and measurements of sense of humor. They could have brought it up.

There are also books that discuss funny in which the authors insist there’s nothing funny about the funny they’re discussing. Take Jeremy Dauber's Jewish Comedy: A Serious History and Ruth Wisse's No Joke: Making Jewish Comedy. both of which insist on their own seriousness and even use colons (which is the universal warning symbol against reading pleasure) but I don’t see the connections there either.

I find this odd.

Much of this peak in influence, activity, and creative intensity was between the 1930s and the 1950s. Also between the 1930s and the 1950s were the 1940s. Which brings us to …

Holocaust Studies has nothing to do with comedy. There are certainly studies of comedy in Germany at the time; about how daily life including jokes persisted; and even a movie called The Last Laugh by Ferne Pearlstein about making jokes about the Holocaust. But none of this goes for the gold ring. I’m not talking about taboo or right and wrong or social norms or even healing. I’m talking about History with a capital H: how did we became utterly hilarious during the Holocaust?

Why is this not on Netflix?

*

Here’s how I got interested: My novel How to Find Your Way in the Dark is set between 1937 and 1947 in rural Massachusetts, Hartford, Connecticut, and the Catskills in New York (among other places). I set a good chunk of it at Grossinger's in Liberty, New York in 1943, which was the premiere Jewish resort. To understand Grossinger's I read the local newspapers that had been available to every influential Jewish guest and every world-class Jewish musical, comedic, or theatrical act that passed through Grossinger's.

How many Jews? How many acts? How influential?

I tried to find out but I couldn’t (not within reason). My hunch? Every political, financial, artistic, and intellectually influential Jew on America's eastern seaboard passed through Grossinger's and read those newspapers in the early 1940s.

Is that true? No. But for the sake of this discussion, it’s close enough for rock n’ roll and here's why I can say that (I get the following numbers from Tania Grossinger’s Growing Up at Grossinger’s (2008)): By the mid-1940s, every week, Grossinger's ordered 300 standing ribs of beef for steaks and roast beef, 1,000 pounds of poultry, 27,000 eggs—all cracked by a woman named Rosie by hand—1,000 pounds of potatoes, 500 pounds of Nova Scotia lox, 70 cases of fresh oranges for juice alone, and 700 pounds of coffee. Every single morning the bakery produced 4,600 rolls and another 4,600 mini pastries. They made 36 pounds of cookies with every meal and 800 portions of pie, and the guests had a choice of at least three kinds of pie during lunch and dinner. Grossinger’s covered almost 850 acres of land, and was the home to thousands of guests every week. They had 60 chambermaids and twenty women in the laundry room washing 7,500 sheets and pillowcases and 20,000 bath towels every week.

That's a lot of Jews.

Were they influential? Grossinger's was one hundred miles from Manhattan, which had the largest (and most influential) Jewish community. Grossinger's was the premiere resort and therefore the place to see and be seen. Is this a deductive argument rather than an empirical one? Yes. But it's a good one and an excellent place to begin an enquiry.

I read the newspapers from almost every day between 1938 and 1944. I read a lot of local papers — like the Examiner-Recorder, the Hartford Courant and the Fitchberg Sentinel and others (including the New York Times and Boston Globe) — that pulled their international news from AP and elsewhere. That means, I was reading what the people there were reading at the time. And while they didn't know what we know today, I'm here to say that they did know a lot; a lot more than we often admit to each other or ourselves. Beatings, murders, deportations, humiliations, disenfranchisement … it was all there, if not (yet) the death camps. I could go on but my point is this: The most funny and the most not-funny of Jewish life was printed on paper and under the noses of the people laughing it up.

As it happens, I’m not only a novelist but an academic by training (I have a Ph.D. in international relations and a couple of masters degrees) and in my head alarms are sounding like Aaaoooogha, Aaoooogha, Aaooogh. These, to me, are not a signal to dive like a submarine but to rise above; above what we know and what we now understand about how individuals and entire cultures attend to comedy and tragedy so that the human experience can be more greatly appreciated and enriched and used as a guide for the perplexed (to coin a term). Because hidden inside this rich-point of investigation are secrets about what it means to be alive; what it means, personally and communally, to be — on one hand — parochial, provincial, dismissive, exclusionary and even scornful of what is foreign and strange and distant and irrelevant to us, while — on the other — being responsive and attentive, empathetic and engaged with the worst of what humanity can throw at us. It may bring us a little closer to an understanding of joy; the joy that God (if there is a God) surely wants for us: joy in the face of darkness. Joy as a response to the darkness.

About the Creator

Derek B. Miller

Dr. Derek B. Miller is an American novelist and political scientist. He is Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy and is the author of six novels, including HOW TO FIND YOUR WAY IN THE DARK.

Comments (1)

GREAT CONTENT