Sitting in a full-house matinee performance of The Choral, it was hard to deny that the age demographics skewed upwards. I felt positively youthful. A friend of mine had tried to entice her teenaged daughter to see it, but she declined with a “It looks boring.” A clear generation divide. Ironic, really – as this is a key theme of the work – how different generations fail to see each other. It opens with a too young teenaged boy tasked with the delivery of telegraphs to war-widowed families.

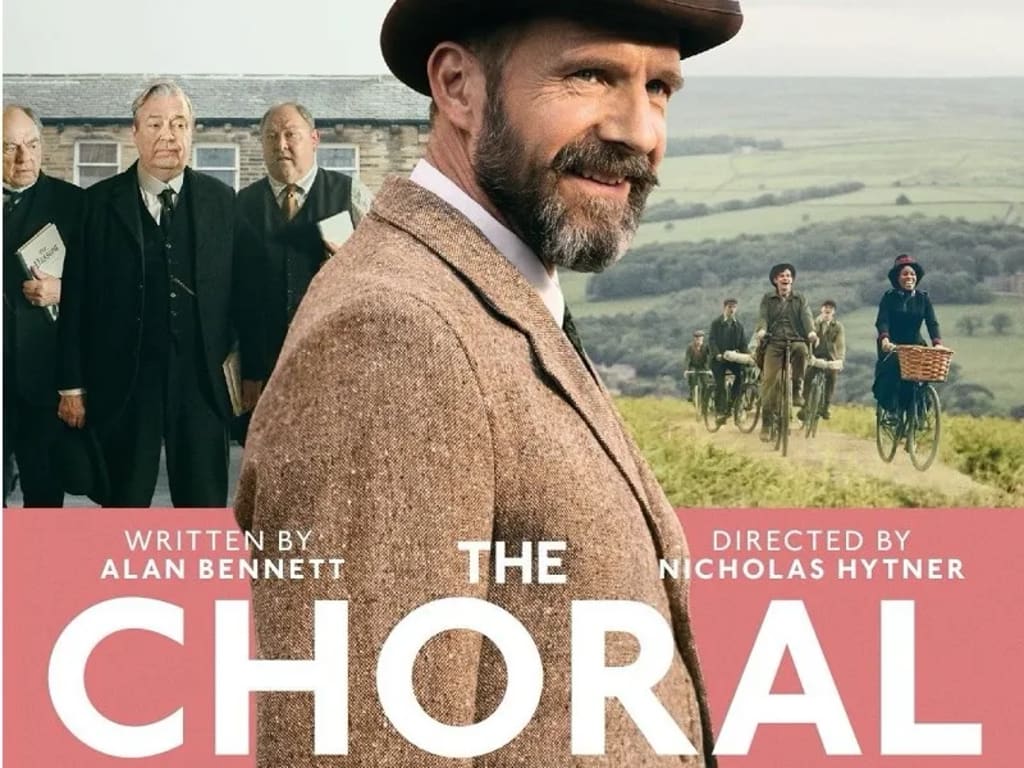

The Choral is a historical comedy drama written by Alan Bennett and directed by Nicholas Hytner. It is set in the fictional West Yorkshire town of Ramsden in 1916. Ramsden looks like a National Trust Heritage Site. It is stone-built quaint surrounded by hills from which we can see the smoke of the mills. (Although we don’t see their dust and soot when walking the cobbled streets or standing on a corner of a well-tended terrace street. Even the amputations of returning soldiers look clean).

The plot is ostensibly set around the Choral Society and the need to recruit new, younger singers and a choir master against the backdrop of disappearing working age men to war effort. A problem soon to be exacerbated by conscription. Dr. Guthrie (Ralph Fiennes) is recruited as the choir master. It is a contentious choice as he had lived in Germany, is an atheist, and also has his “peculiarities” (coded homosexuality). After a discussion of suitable music, the choice is to produce Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius. Elgar isn’t German and the fact that the lyrics are by a Roman Catholic (said with appropriate disgust) can be overlooked.

While Fiennes is the star and he gives a fastidious performance of a man with a passion for music, struggling with grief and simmering anger, this is an ensemble piece. The cast comprises some stalwarts of the British Film and TV industry, as well as introducing new talent. It is full of vivid character studies and bittersweet moments.

In all, it looks quite cosy, a Britain of tourist boards and tradition. But this undercuts the writing which is at times bitterly spiky. Amongst the flat caps, flat vowels and quiet acceptance is something much less sentimental.

I could hear the audience laugh as teenaged boys larked about and at the class-ridden comedy of errors. But I couldn’t tell, if like me, they cried, or felt the gut-punch each time every time someone uttered, “It will all be over by Christmas.”

Bennett can write a funny one-liner. And he can highlight the idiocy of a class system both through direct speech and the hypocrisy of some of its agents. It is written with a knowing about the waste of youth. Not the old cliché that youth is wasted on the young. But that it is wasted by a class and generation above, intent on control, on a particular social order. And this is highlighted through a prism of sexuality, questions about the role of sexuality, companionship, relationships.

There are a number of plots and subplots: A pianist stuck with a crush on the choirmaster. A salvation army member who can only see sex as religious dilemma. A woman who sells sex to survive and rides the storm of judgement. A grieving father who needs his wife to live again. Virgins worried about conscription as a way of stopping their access to adult sexuality. A couple split by war and unable to reconcile on his wounded return. (This was the strongest written dilemma and one of the lingering memories of the film is their last meeting on a lonely hillside, with sex as duty, loyalty, unfinished business, instead of words, with no way for a happy carefree ending for either of them). All of these stories took me close to an emotional brink, and then I was brought back by a well-timed one-liner.

My first impression was that it didn’t quite get the balance right. It was too cosy over the spiky injustice. But as I write this review I can feel my opinion shift. I would have liked more space for some of the characters and plots lines to get into the depths of the emotion. But now as I try to come up with a punchy ending I realise a return to a gag makes more sense. The ridiculous is more important than the sublime.

This is a good film that carefully treads the line between cosy and spiky. It gets angry. It asks big questions and then retreats to a nice cup of tea.

War – what is it good for? Well, it could disrupt the social order, if only briefly.

And music – what is it good for? To make a soul soar briefly before falling back to earth to be handed a rifle.

If you've enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you'd like to support my writing, you can do so by leaving a one-time tip or a regular pledge. Thank you.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Comments (4)

This was a thoughtful and engaging review. You painted a vivid picture of the film and its atmosphere.

Thank you for bringing my attention to this.

When my daughter asked me whether I wanted to see this movie I equivocated. Reading your review makes me think it is definitely not for me. Alan Bennett, Ralph (professor of over-acting) F, quaint English provincial towns, grief and anger (cheapest of dramatic choices other than shouting, swearing, shooting and shagging) and a bunch of singers getting together to.... sing. Which makes this a great review for those who, like me, need help choosing. You really ought to start a movie mag. I would definitely subscribe

Gracefully written review which both shows the minor flaws of the films and the powerful strengths. Excellent review, Rachel. This is a film I want to explore.